21 Jul 2020

This is an ongoing series of posts on ELF Binary Relocations and Thread

Local Storage. This article covers only Thread Local Storage and assumes

the reader has had a primer in ELF Relocations, if not please start with

my previous article ELF Binaries and Relocation Entries.

This is the third part in an illustrated 3 part series covering:

In the last article we covered how Thread Local Storage (TLS) works at runtime,

but how do we get there? How does the compiler and linker create the memory

structures and code fragments described in the previous article?

In this article we will discuss how TLS relocations are is implemented. Our

outline:

As before, the examples in this article can be found in my tls-examples

project. Please check it out.

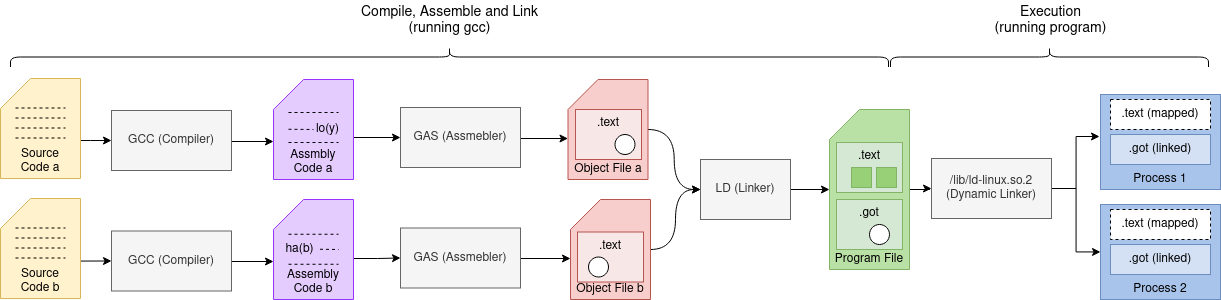

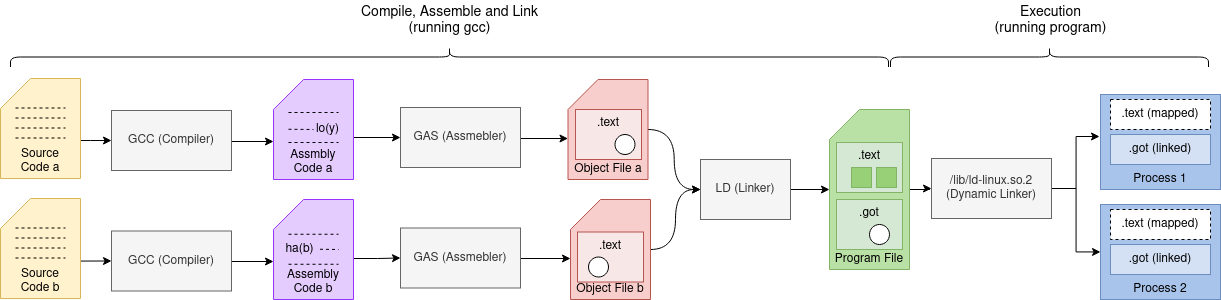

I will assume here that most people understand what a compiler and assembler

basically do. In the sense that compiler will compile routines

written C code or something similar to assembly language. It is then up to the

assembler to turn that assembly code into machine code to run on a CPU.

That is a big part of what a toolchain does, and it’s pretty much that simple if

we have a single file of source code. But usually we don’t have a single file,

we have the multiple files, the c runtime,

crt0 and other libraries like

libc. These all need to be

put together into our final program, that is where the complexities of the

linker comes in.

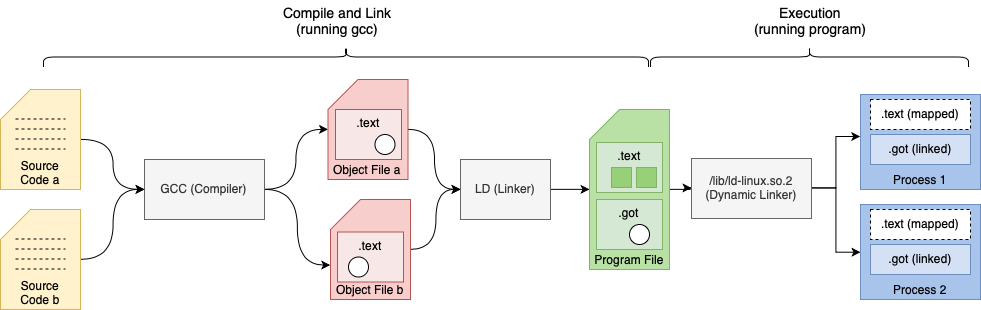

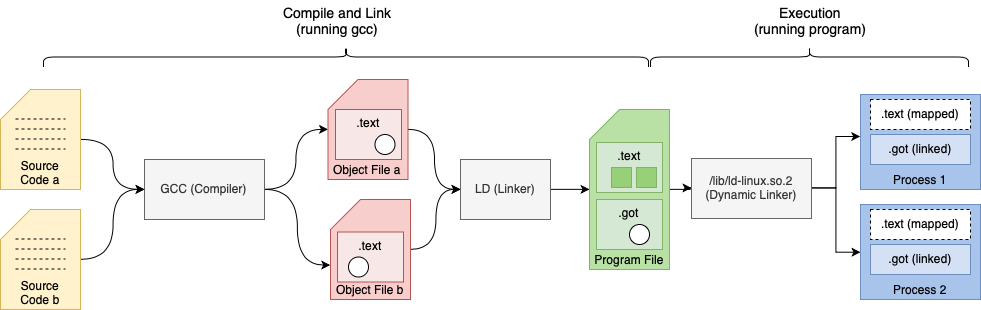

In this article I will cover how variables in our source code (symbols) traverse

the toolchain from code to the memory in our final running program. A picture that looks

something like this:

The Compiler

First we start off with how relocations are created and emitted in the compiler.

As I work primarily on the GNU toolchain with

it’s GCC compiler we will look at that, let’s get started.

GCC Legitimize Address

To start we define a symbol as named address in memory. This address can be

a program variable where data is stored or function reference to where a

subroutine starts.

In GCC we have have TARGET_LEGITIMIZE_ADDRESS, the OpenRISC implementation

being or1k_legitimize_address().

It takes a symbol (memory address) and makes it usable in our CPU by generating RTX

sequences that are possible on our CPU to load that address into a register.

RTX represents a tree node in GCC’s register transfer language (RTL). The RTL

Expression is used to express our algorithm as a series of register transfers.

This is used as register transfer is basically what a CPU does.

A snippet from legitimize_address() function is below. The argument x

represents our input symbol (memory address) that we need to make usable by our

CPU. This code uses GCC internal API’s to emit RTX code sequences.

static rtx

or1k_legitimize_address (rtx x, rtx /* unused */, machine_mode /* unused */)

...

case TLS_MODEL_NONE:

t1 = can_create_pseudo_p () ? gen_reg_rtx (Pmode) : scratch;

if (!flag_pic)

{

emit_insn (gen_rtx_SET (t1, gen_rtx_HIGH (Pmode, x)));

return gen_rtx_LO_SUM (Pmode, t1, x);

}

else if (is_local)

{

crtl->uses_pic_offset_table = 1;

t2 = gen_sym_unspec (x, UNSPEC_GOTOFF);

emit_insn (gen_rtx_SET (t1, gen_rtx_HIGH (Pmode, t2)));

emit_insn (gen_add3_insn (t1, t1, pic_offset_table_rtx));

return gen_rtx_LO_SUM (Pmode, t1, copy_rtx (t2));

}

else

{

...

We can read the code snippet above as follows:

- This is for the non

TLS case as we see TLS_MODEL_NONE.

- We reserve a temporary register

t1.

- If not using Position-independent code (

flag_pic) we do:

- Emit an instruction to put the high bits of

x into our temporary register t1.

- Return the sum of

t1 and the low bits of x.

- Otherwise if the symbol is static (

is_local) we do:

- Mark the global state that this object file uses the

uses_pic_offset_table.

- We create a Global Offset Table offset variable

t2.

- Emit an instruction to put the high bits of

t2 (the GOT offset) into out temporary register t1.

- Emit an instruction to put the sum of

t1 (high bits of t2) and the GOT into t1`.

- Return the sum of

t1 and the low bits of t1.

You may have noticed that the local symbol still used the global offset

table (GOT). This is

because Position-idependent code requires using the GOT to reference symbols.

An example, from nontls.c:

static int x;

int *get_x_addr() {

return &x;

}

Example of the non pic case above, when we look at the assembly code generated by GCC

we can see the following:

.file "nontls.c"

.section .text

.local x

.comm x,4,4

.align 4

.global get_x_addr

.type get_x_addr, @function

get_x_addr:

l.addi r1, r1, -8 # \

l.sw 0(r1), r2 # | function prologue

l.addi r2, r1, 8 # |

l.sw 4(r1), r9 # /

l.movhi r17, ha(x) # \__ legitimize address of x into r17

l.addi r17, r17, lo(x) # /

l.or r11, r17, r17 # } place result in return register r11

l.lwz r2, 0(r1) # \

l.lwz r9, 4(r1) # | function epilogue

l.addi r1, r1, 8 # |

l.jr r9 # |

l.nop # /

.size get_x_addr, .-get_x_addr

.ident "GCC: (GNU) 9.0.1 20190409 (experimental)"

Example of the local pic case above the same code compiled with the -fPIC GCC option

looks like the following:

.file "nontls.c"

.section .text

.local x

.comm x,4,4

.align 4

.global get_x_addr

.type get_x_addr, @function

get_x_addr:

l.addi r1, r1, -8 # \

l.sw 0(r1), r2 # | function prologue

l.addi r2, r1, 8 # |

l.sw 4(r1), r9 # /

l.jal 8 # \

l.movhi r19, gotpchi(_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_-4) # | PC relative, put

l.ori r19, r19, gotpclo(_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0) # | GOT into r19

l.add r19, r19, r9 # /

l.movhi r17, gotoffha(x) # \

l.add r17, r17, r19 # | legitimize address of x into r17

l.addi r17, r17, gotofflo(x) # /

l.or r11, r17, r17 # } place result in return register r11

l.lwz r2, 0(r1) # \

l.lwz r9, 4(r1) # | function epilogue

l.addi r1, r1, 8 # |

l.jr r9 # |

l.nop # /

.size get_x_addr, .-get_x_addr

.ident "GCC: (GNU) 9.0.1 20190409 (experimental)"

TLS and Addend cases are also handled by or1k_legitimize_address().

GCC Print Operand

Once RTX is generated by legitimize address and GCC passes

run all of their optimizations the RTX needs to be printed out as assembly code. During

this process relocations are printed by GCC macros TARGET_PRINT_OPERAND_ADDRESS

and TARGET_PRINT_OPERAND. In OpenRISC these defined

by or1k_print_operand_address()

and or1k_print_operand().

Let us have a look at or1k_print_operand_address().

/* Worker for TARGET_PRINT_OPERAND_ADDRESS.

Prints the argument ADDR, an address RTX, to the file FILE. The output is

formed as expected by the OpenRISC assembler. Examples:

RTX OUTPUT

(reg:SI 3) 0(r3)

(plus:SI (reg:SI 3) (const_int 4)) 0x4(r3)

(lo_sum:SI (reg:SI 3) (symbol_ref:SI ("x"))) lo(x)(r3) */

static void

or1k_print_operand_address (FILE *file, machine_mode, rtx addr)

{

rtx offset;

switch (GET_CODE (addr))

{

case REG:

fputc ('0', file);

break;

case ...

case LO_SUM:

offset = XEXP (addr, 1);

addr = XEXP (addr, 0);

print_reloc (file, offset, 0, RKIND_LO);

break;

default: ...

}

fprintf (file, "(%s)", reg_names[REGNO (addr)]);

}

The above code snippet can be read as we explain below, but let’s first

make some notes:

- The input RTX

addr for TARGET_PRINT_OPERAND_ADDRESS will usually contain

a register and an offset typically this is used for LOAD and STORE

operations.

- Think of the RTX

addr as a node in an AST.

- The RTX node with code

REG and SYMBOL_REF are always leaf nodes.

With that, and if we use the or1k_print_operand_address() c comments above as examples

of some RTX addr input we will have:

RTX | (reg:SI 3) (lo_sum:SI (reg:SI 3) (symbol_ref:SI("x")))

-----------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

TREE |

(code) | (code:REG regno:3) (code:LO_SUM)

/ \ | / \

(0) (1) | (code:REG regno:3) (code:SYMBOL_REF "x")

We can now read the above snippet as:

- First get the

CODE of the RTX.

- If

CODE is REG (a register) than our offset can be 0.

- If

IS is LO_SUM (an addition operation) then we need to break it down to:

- Arg

0 is our new addr RTX (which we assume is a register)

- Arg

1 is an offset (which we then print with print_reloc())

- Second print out the register name now in

addr i.e. “r3”.

The code of or1k_print_operand() is similar and the reader may be inclined to

read more details. With that we can move on to the assembler.

TLS cases are also handled inside of the print_reloc() function.

The Assembler

In the GNU Toolchain our assembler is GAS, part of binutils.

The code that handles relocations is found in the function

parse_reloc()

found in opcodes/or1k-asm.c. The function parse_reloc() is the direct counterpart of GCC’s print_reloc()

discussed above. This is actually part of or1k_cgen_parse_operand()

which is wired into our assembler generator CGEN used for parsing operands.

If we are parsing a relocation like the one from above lo(x) then we can

isolate the code that processes that relocation.

static const bfd_reloc_code_real_type or1k_imm16_relocs[][6] = {

{ BFD_RELOC_LO16,

BFD_RELOC_OR1K_SLO16,

...

BFD_RELOC_OR1K_TLS_LE_AHI16 },

};

static int

parse_reloc (const char **strp)

{

const char *str = *strp;

enum or1k_rclass cls = RCLASS_DIRECT;

enum or1k_rtype typ;

...

else if (strncasecmp (str, "lo(", 3) == 0)

{

str += 3;

typ = RTYPE_LO;

}

...

*strp = str;

return (cls << RCLASS_SHIFT) | typ;

}

This uses strncasecmp to match

our "lo(" string pattern. The returned result is a relocation type and relocation class

which are use to lookup the relocation BFD_RELOC_LO16 in the or1k_imm16_relocs[][] table

which is indexed by relocation class and relocation class.

The assembler will encode that into the ELF binary. For TLS relocations the exact same

pattern is used.

The Linker

In the GNU Toolchain our object linker is the GNU linker LD, also part of the

binutils project.

The GNU linker uses the framework

BFD or Binary File

Descriptor which

is a beast. It is not only used in the linker but also used in GDB, the GNU

Simulator and the objdump tool.

What makes this possible is a rather complex API.

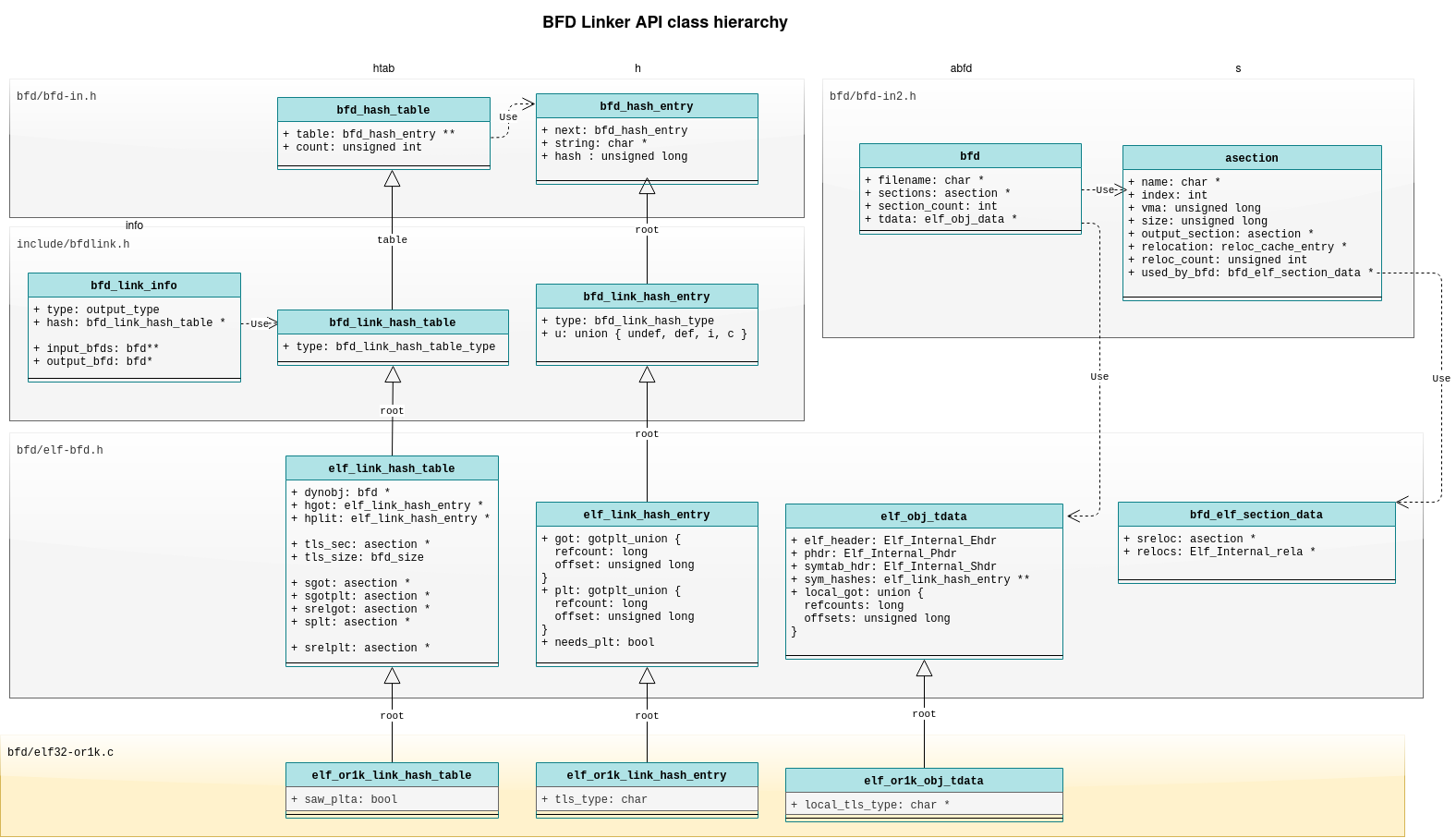

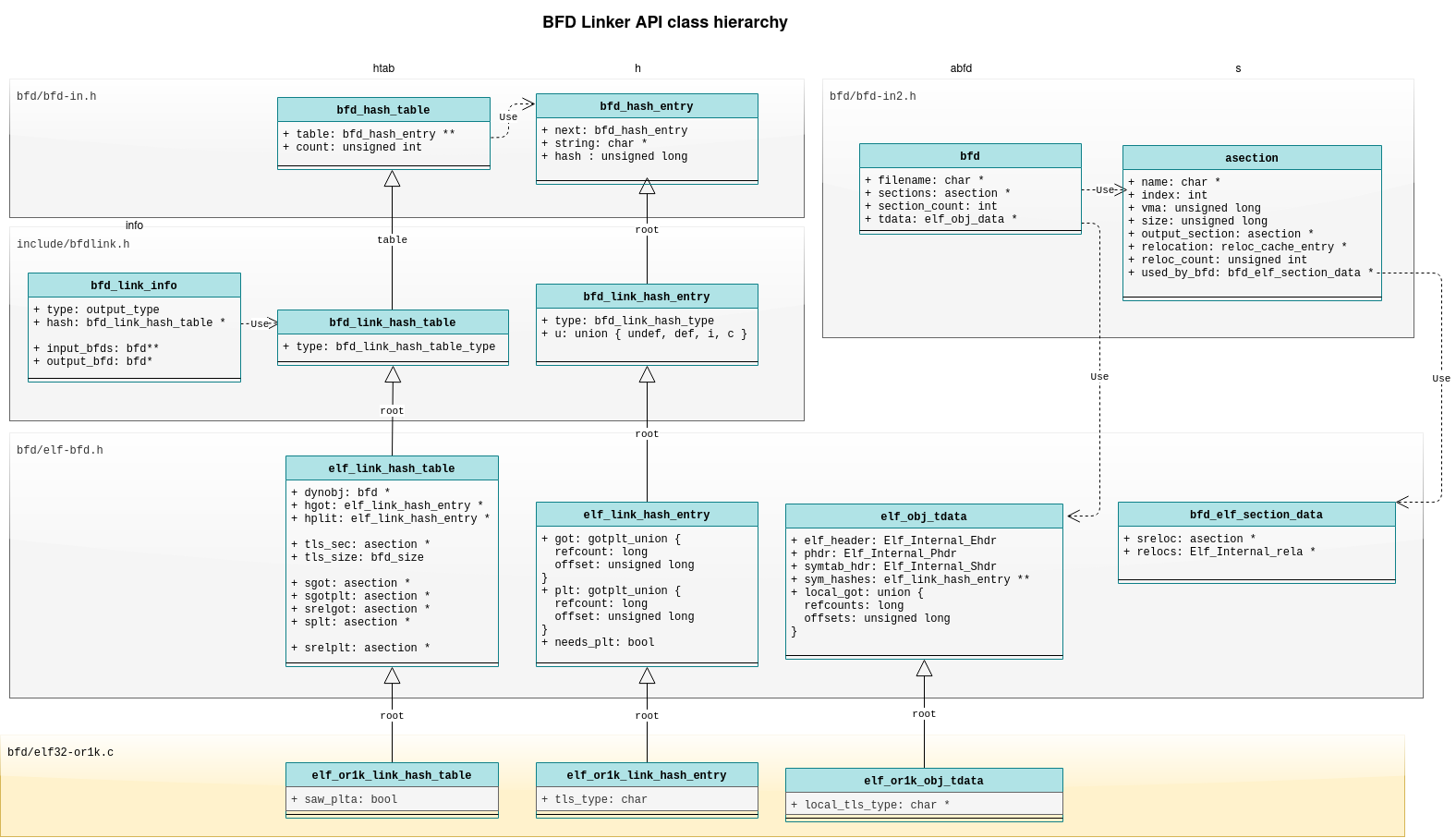

BFD Linker API

The BFD API is a generic binary file access API. It has been designed to support multiple

file formats and architectures via an object oriented, polymorphic API all written in c. It supports file formats

including a.out,

COFF and

ELF as well as

unexpected file formats like

verilog hex memory dumps.

Here we will concentrate on the BFD ELF implementation.

The API definition is split across multiple files which include:

- bfd/bfd-in.h - top level generic APIs including

bfd_hash_table

- bfd/bfd-in2.h - top level binary file APIs including

bfd and asection

- include/bfdlink.h - generic bfd linker APIs including

bfd_link_info and bfd_link_hash_table

- bfd/elf-bfd.h - extensions to the APIs for ELF binaries including

elf_link_hash_table

bfd/elf{wordsize}-{architecture}.c - architecture specific implementations

For each architecture implementations are defined in bfd/elf{wordsize}-{architecture}.c. For

example for OpenRISC we have

bfd/elf32-or1k.c.

Throughout the linker code we see access to the BFD Linker and ELF APIs. Some key symbols to watch out for include:

info - A reference to bfd_link_info top level reference to all linker

state.htab - A pointer to elf_or1k_link_hash_table from or1k_elf_hash_table (info), a hash

table on steroids which stores generic link state and arch specific state, it’s also a hash

table of all global symbols by name, contains:

htab->root.splt - the output .plt sectionhtab->root.sgot - the output .got sectionhtab->root.srelgot - the output .relgot section (relocations against the got)htab->root.sgotplt - the output .gotplt sectionhtab->root.dynobj - a special bfd to which sections are added (created in or1k_elf_check_relocs)

sym_hashes - From elf_sym_hashes (abfd) a list of for global symbols

in a bfd indexed by the relocation index ELF32_R_SYM (rel->r_info).h - A pointer to a struct elf_link_hash_entry, represents link state

of a global symbol, contains:

h->got - A union of different attributes with different roles based on link phase.h->got.refcount - used during phase 1 to count the symbol .got section referencesh->got.offset - used during phase 2 to record the symbol .got section offseth->plt - A union with the same function as h->got but used for the .plt section.h->root.root.string - The symbol name

local_got- an array of unsigned long from elf_local_got_refcounts (ibfd) with the same

function to h->got but for local symbols, the function of the unsigned long is changed base

on the link phase. Ideally this should also be a union.tls_type - Retrieved by ((struct elf_or1k_link_hash_entry *) h)->tls_type used to store the

tls_type of a global symbol.local_tls_type - Retrieved by elf_or1k_local_tls_type(abfd) entry to store tls_type for local

symbols, when h is NULL.root - The struct field root is used in subclasses to represent the parent class, similar to how super is used

in other languages.

Putting it all together we have a diagram like the following:

Now that we have a bit of understanding of the data structures

we can look to the link algorithm.

The link process in the GNU Linker can be thought of in phases.

Phase 1 - Book Keeping (check_relocs)

The or1k_elf_check_relocs() function is called during the first phase to

do book keeping on relocations. The function signature looks like:

static bfd_boolean

or1k_elf_check_relocs (bfd *abfd,

struct bfd_link_info *info,

asection *sec,

const Elf_Internal_Rela *relocs)

#define elf_backend_check_relocs or1k_elf_check_relocs

The arguments being:

abfd - The current elf object file we are working oninfo - The BFD APIsec - The current elf section we are working onrelocs - The relocations from the current section

It does the book keeping by looping over relocations for the provided section

and updating the local and global symbol properties.

For local symbols:

...

else

{

unsigned char *local_tls_type;

/* This is a TLS type record for a local symbol. */

local_tls_type = (unsigned char *) elf_or1k_local_tls_type (abfd);

if (local_tls_type == NULL)

{

bfd_size_type size;

size = symtab_hdr->sh_info;

local_tls_type = bfd_zalloc (abfd, size);

if (local_tls_type == NULL)

return FALSE;

elf_or1k_local_tls_type (abfd) = local_tls_type;

}

local_tls_type[r_symndx] |= tls_type;

}

...

else

{

bfd_signed_vma *local_got_refcounts;

/* This is a global offset table entry for a local symbol. */

local_got_refcounts = elf_local_got_refcounts (abfd);

if (local_got_refcounts == NULL)

{

bfd_size_type size;

size = symtab_hdr->sh_info;

size *= sizeof (bfd_signed_vma);

local_got_refcounts = bfd_zalloc (abfd, size);

if (local_got_refcounts == NULL)

return FALSE;

elf_local_got_refcounts (abfd) = local_got_refcounts;

}

local_got_refcounts[r_symndx] += 1;

}

The above is pretty straight forward and we can read as:

- First part is for storing local symbol

TLS type information:

- If the

local_tls_type array is not initialized:

- Allocate it, 1 entry for each local variable

- Record the TLS type in

local_tls_type for the current symbol

- Second part is for recording

.got section references:

- If the

local_got_refcounts array is not initialized:

- Allocate it, 1 entry for each local variable

- Record a reference by incrementing

local_got_refcounts for the current symbol

For global symbols, it’s much more easy we see:

...

if (h != NULL)

((struct elf_or1k_link_hash_entry *) h)->tls_type |= tls_type;

else

...

if (h != NULL)

h->got.refcount += 1;

else

...

As the tls_type and refcount fields are available directly on each

hash_entry handling global symbols is much easier.

- First part is for storing

TLS type information:

- Record the TLS type in

tls_type for the current hash_entry

- Second part is for recording

.got section references:

- Record a reference by incrementing

got.refcounts for the hash_entry

The above is repeated for all relocations and all input sections. A few other

things are also done including accounting for .plt entries.

Phase 2 - creating space (size_dynamic_sections + _bfd_elf_create_dynamic_sections)

The or1k_elf_size_dynamic_sections()

function iterates over all input object files to calculate the size required for

output sections. The _bfd_elf_create_dynamic_sections() function does the

actual section allocation, we use the generic version.

Setting up the sizes of the .got section (global offset table) and .plt

section (procedure link table) is done here.

The definition is as below:

static bfd_boolean

or1k_elf_size_dynamic_sections (bfd *output_bfd ATTRIBUTE_UNUSED,

struct bfd_link_info *info)

#define elf_backend_size_dynamic_sections or1k_elf_size_dynamic_sections

#define elf_backend_create_dynamic_sections _bfd_elf_create_dynamic_sections

The arguments to or1k_elf_size_dynamic_sections() being:

output_bfd - Unused, the output elf objectinfo - the BFD API which provides access to everything we need

Internally the function uses:

htab - from or1k_elf_hash_table (info)

htab->root.dynamic_sections_created - true if sections like .interp have been created by the linker

ibfd - a bfd pointer from info->input_bfds, represents an input object when iterating.s->size - represents the output .got section size, which we will be

incrementing.srel->size - represents the output .got.rela section size, which will

contain relocations against the .got section

During the first part of phase 2 we set .got and .got.rela section sizes

for local symbols with this code:

/* Set up .got offsets for local syms, and space for local dynamic

relocs. */

for (ibfd = info->input_bfds; ibfd != NULL; ibfd = ibfd->link.next)

{

...

local_got = elf_local_got_refcounts (ibfd);

if (!local_got)

continue;

symtab_hdr = &elf_tdata (ibfd)->symtab_hdr;

locsymcount = symtab_hdr->sh_info;

end_local_got = local_got + locsymcount;

s = htab->root.sgot;

srel = htab->root.srelgot;

local_tls_type = (unsigned char *) elf_or1k_local_tls_type (ibfd);

for (; local_got < end_local_got; ++local_got)

{

if (*local_got > 0)

{

unsigned char tls_type = (local_tls_type == NULL)

? TLS_UNKNOWN

: *local_tls_type;

*local_got = s->size;

or1k_set_got_and_rela_sizes (tls_type, bfd_link_pic (info),

&s->size, &srel->size);

}

else

*local_got = (bfd_vma) -1;

if (local_tls_type)

++local_tls_type;

}

}

Here, for example, we can see we iterate over each input elf object ibfd and

each local symbol (local_got) we try and update s->size and srel->size to

account for the required size.

The above can be read as:

- For each

local_got entry:

- If the local symbol is used in the

.got section:

- Get the

tls_type byte stored in the local_tls_type array

- Set the offset

local_got to the section offset s->size, that is used

in phase 3 to tell us where we need to write the symbol into the .got

section.

- Update

s->size and srel->size using or1k_set_got_and_rela_sizes()

- If the local symbol is not used in the

.got section:

- Set the offset

local_got to the -1, to indicate not used

In the next part of phase 2 we allocate space for all global symbols by

iterating through symbols in htab with the allocate_dynrelocs iterator. To

do that we call:

elf_link_hash_traverse (&htab->root, allocate_dynrelocs, info);

Inside allocate_dynrelocs() we record the space used for relocations and

the .got and .plt sections. Example:

if (h->got.refcount > 0)

{

asection *sgot;

bfd_boolean dyn;

unsigned char tls_type;

...

sgot = htab->root.sgot;

h->got.offset = sgot->size;

tls_type = ((struct elf_or1k_link_hash_entry *) h)->tls_type;

dyn = htab->root.dynamic_sections_created;

dyn = WILL_CALL_FINISH_DYNAMIC_SYMBOL (dyn, bfd_link_pic (info), h);

or1k_set_got_and_rela_sizes (tls_type, dyn,

&sgot->size, &htab->root.srelgot->size);

}

else

h->got.offset = (bfd_vma) -1;

The above, with h being our global symbol, a pointer to struct elf_link_hash_entry,

can be read as:

- If the symbol will be in the

.got section:

- Get the global reference to the

.got section and put it in sgot

- Set the got location

h->got.offset for the symbol to the current got

section size htab->root.sgot.

- Set

dyn to true if we will be doing a dynamic link.

- Call

or1k_set_got_and_rela_sizes() to update the sizes for the .got

and .got.rela sections.

- If the symbol is going to be in the

.got section:

- Set the got location

h->got.offset to -1

The function or1k_set_got_and_rela_sizes() used above is used to increment

.got and .rela section sizes accounting for if these are TLS symbols, which

need additional entries and relocations.

Phase 3 - linking (relocate_section)

The or1k_elf_relocate_section()

function is called to fill in the relocation holes in the output binary .text

section. It does this by looping over relocations and writing to the .text

section the correct symbol value (memory address). It also updates other output

binary sections like the .got section. Also, for dynamic executables and

libraries new relocations may be written to .rela sections.

The function signature looks as follows:

static bfd_boolean

or1k_elf_relocate_section (bfd *output_bfd,

struct bfd_link_info *info,

bfd *input_bfd,

asection *input_section,

bfd_byte *contents,

Elf_Internal_Rela *relocs,

Elf_Internal_Sym *local_syms,

asection **local_sections)

#define elf_backend_relocate_section or1k_elf_relocate_section

The arguments to or1k_elf_relocate_sectioni() being:

output_bfd - the output elf object we will be writing toinfo - the BFD API which provides access to everything we needinput_bfd - the current input elf object being iterated overinput_section the current .text section in the input elf object being iterated

over. From here we get .text section output details for pc relative relocations:

input_section->output_section->vma - the location of the output section.input_section->output_offset - the output offset

contents - the output file buffer we will write torelocs - relocations from the current input sectionlocal_syms - an array of local symbols used to get the relocation value for local symbolslocal_sections - an array input sections for local symbols, used to get the relocation value for local symbols

Internally the function uses:

- or1k_elf_howto_table - not

mentioned until now, but an array of

howto structs indexed by relocation enum.

The howto struct expresses the algorithm required to update the relocation.

relocation - a bfd_vma the value of the relocation symbol (memory address)

to be written to the output file.

in the output file that needs to be updated for the relocation.value - the value that needs to be written to the relocation location.

During the first part of relocate_section we see:

if (r_symndx < symtab_hdr->sh_info)

{

sym = local_syms + r_symndx;

sec = local_sections[r_symndx];

relocation = _bfd_elf_rela_local_sym (output_bfd, sym, &sec, rel);

name = bfd_elf_string_from_elf_section

(input_bfd, symtab_hdr->sh_link, sym->st_name);

name = name == NULL ? bfd_section_name (sec) : name;

}

else

{

bfd_boolean unresolved_reloc, warned, ignored;

RELOC_FOR_GLOBAL_SYMBOL (info, input_bfd, input_section, rel,

r_symndx, symtab_hdr, sym_hashes,

h, sec, relocation,

unresolved_reloc, warned, ignored);

name = h->root.root.string;

}

This can be read as:

- If the current symbol is a local symbol:

- We initialize

relocation to the local symbol value using _bfd_elf_rela_local_sym().

- Otherwise the current symbol is global:

- We use the

RELOC_FOR_GLOBAL_SYMBOL() macro to initialize relocation.

During the next part we use the howto information to update the relocation value, and also

add relocations to the output file. For example:

case R_OR1K_TLS_GD_HI16:

case R_OR1K_TLS_GD_LO16:

case R_OR1K_TLS_GD_PG21:

case R_OR1K_TLS_GD_LO13:

case R_OR1K_TLS_IE_HI16:

case R_OR1K_TLS_IE_LO16:

case R_OR1K_TLS_IE_PG21:

case R_OR1K_TLS_IE_LO13:

case R_OR1K_TLS_IE_AHI16:

{

bfd_vma gotoff;

Elf_Internal_Rela rela;

asection *srelgot;

bfd_byte *loc;

bfd_boolean dynamic;

int indx = 0;

unsigned char tls_type;

srelgot = htab->root.srelgot;

/* Mark as TLS related GOT entry by setting

bit 2 to indcate TLS and bit 1 to indicate GOT. */

if (h != NULL)

{

gotoff = h->got.offset;

tls_type = ((struct elf_or1k_link_hash_entry *) h)->tls_type;

h->got.offset |= 3;

}

else

{

unsigned char *local_tls_type;

gotoff = local_got_offsets[r_symndx];

local_tls_type = (unsigned char *) elf_or1k_local_tls_type (input_bfd);

tls_type = local_tls_type == NULL ? TLS_NONE

: local_tls_type[r_symndx];

local_got_offsets[r_symndx] |= 3;

}

/* Only process the relocation once. */

if ((gotoff & 1) != 0)

{

gotoff += or1k_initial_exec_offset (howto, tls_type);

/* The PG21 and LO13 relocs are pc-relative, while the

rest are GOT relative. */

relocation = got_base + (gotoff & ~3);

if (!(r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_GD_PG21

|| r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_GD_LO13

|| r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_IE_PG21

|| r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_IE_LO13))

relocation -= got_sym_value;

break;

}

...

/* Static GD. */

else if ((tls_type & TLS_GD) != 0)

{

bfd_put_32 (output_bfd, 1, sgot->contents + gotoff);

bfd_put_32 (output_bfd, tpoff (info, relocation, dynamic),

sgot->contents + gotoff + 4);

}

gotoff += or1k_initial_exec_offset (howto, tls_type);

...

/* Static IE. */

else if ((tls_type & TLS_IE) != 0)

bfd_put_32 (output_bfd, tpoff (info, relocation, dynamic),

sgot->contents + gotoff);

/* The PG21 and LO13 relocs are pc-relative, while the

rest are GOT relative. */

relocation = got_base + gotoff;

if (!(r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_GD_PG21

|| r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_GD_LO13

|| r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_IE_PG21

|| r_type == R_OR1K_TLS_IE_LO13))

relocation -= got_sym_value;

}

break;

Here we process the relocation for TLS General Dynamic and Initial Exec relocations. I have trimmed

out the shared cases to save space.

This can be read as:

- Get a reference to the output relocation section

sreloc.

- Get the got offset which we setup during phase 3 for global or local symbols.

- Mark the symbol as using a TLS got entry, this

offset |= 3 trick is

possible because on 32-bit machines we have 2 lower bits free. This

is used during phase 4.

- If we have already processed this symbol once:

- Update

relocation to the location in the output .got section and break, we only need to create .got entries 1 time

- Otherwise populate

.got section entries

- For General Dynamic

- Put 2 entries into the output elf object

.gotsection, a literal 1 and the thread pointer offset

- For Initial Exec

- Put 1 entry into the output elf object

.got section, the thread pointer offset

- Finally update the

relocation to the location in the output .got section

In the last part of the loop we write the relocation value to the output

.text section. This is done with the or1k_final_link_relocate()

function.

r = or1k_final_link_relocate (howto, input_bfd, input_section, contents,

rel->r_offset, relocation + rel->r_addend);

With this the .text section is complete.

Phase 4 - finishing up (finish_dynamic_symbol + finish_dynamic_sections)

During phase 3 above we wrote the .text section out to file. During the

final finishing up phase we need to write the remaining sections. This

includes the .plt section an more writes to the .got section.

This also includes the .plt.rela and .got.rela sections which contain

dynamic relocation entries.

Writing of the data sections is handled by

or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_sections()

and writing of the relocation sections is handled by

or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_symbol(). These are defined as below.

static bfd_boolean

or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_sections (bfd *output_bfd,

struct bfd_link_info *info)

static bfd_boolean

or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_symbol (bfd *output_bfd,

struct bfd_link_info *info,

struct elf_link_hash_entry *h,

Elf_Internal_Sym *sym)

#define elf_backend_finish_dynamic_sections or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_sections

#define elf_backend_finish_dynamic_symbol or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_symbol

A snippet for the or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_sections() shows how when writing to

the .plt section assembly code needs to be injected. This is where the first

entry in the .plt section is written.

else if (bfd_link_pic (info))

{

plt0 = OR1K_LWZ(15, 16) | 8; /* .got+8 */

plt1 = OR1K_LWZ(12, 16) | 4; /* .got+4 */

plt2 = OR1K_NOP;

}

else

{

unsigned ha = ((got_addr + 0x8000) >> 16) & 0xffff;

unsigned lo = got_addr & 0xffff;

plt0 = OR1K_MOVHI(12) | ha;

plt1 = OR1K_LWZ(15,12) | (lo + 8);

plt2 = OR1K_LWZ(12,12) | (lo + 4);

}

or1k_write_plt_entry (output_bfd, splt->contents,

plt0, plt1, plt2, OR1K_JR(15));

elf_section_data (splt->output_section)->this_hdr.sh_entsize = 4;

Here we see a write to output_bfd, this represents the output object file

which we are writing to. The argument splt->contents represents the object

file offset to write to for the .plt section. Next we see the line

elf_section_data (splt->output_section)->this_hdr.sh_entsize = 4

this allows the linker to calculate the size of the section.

A snippet from the or1k_elf_finish_dynamic_symbol() function shows where

we write out the code and dynamic relocation entries for each symbol to

the .plt section.

splt = htab->root.splt;

sgot = htab->root.sgotplt;

srela = htab->root.srelplt;

...

else

{

unsigned ha = ((got_addr + 0x8000) >> 16) & 0xffff;

unsigned lo = got_addr & 0xffff;

plt0 = OR1K_MOVHI(12) | ha;

plt1 = OR1K_LWZ(12,12) | lo;

plt2 = OR1K_ORI0(11) | plt_reloc;

}

or1k_write_plt_entry (output_bfd, splt->contents + h->plt.offset,

plt0, plt1, plt2, OR1K_JR(12));

/* Fill in the entry in the global offset table. We initialize it to

point to the top of the plt. This is done to lazy lookup the actual

symbol as the first plt entry will be setup by libc to call the

runtime dynamic linker. */

bfd_put_32 (output_bfd, plt_base_addr, sgot->contents + got_offset);

/* Fill in the entry in the .rela.plt section. */

rela.r_offset = got_addr;

rela.r_info = ELF32_R_INFO (h->dynindx, R_OR1K_JMP_SLOT);

rela.r_addend = 0;

loc = srela->contents;

loc += plt_index * sizeof (Elf32_External_Rela);

bfd_elf32_swap_reloca_out (output_bfd, &rela, loc);

Here we can see we write 3 things to output_bfd for the single .plt entry.

We write:

- The assembly code to the

.plt section.

- The

plt_base_addr (the first entry in the .plt for runtime lookup) to the .got section.

- And finally a dynamic relocation for our symbol to the

.plt.rela.

With that we have written all of the sections out to our final elf object, and it’s ready

to be used.

GLIBC Runtime Linker

The runtime linker, also referred to as the dynamic linker, will do the final

linking as we load our program and shared libraries into memory. It can process

a limited set of relocation entries that were setup above during phase 4 of

linking.

The runtime linker implementation is found mostly in the

elf/dl-* GLIBC source files. Dynamic relocation processing is handled in by

the _dl_relocate_object()

function in the elf/dl-reloc.c file. The back end macro used for relocation

ELF_DYNAMIC_RELOCATE

is defined across several files including elf/dynamic-link.h

and elf/do-rel.h

Architecture specific relocations are handled by the function elf_machine_rela(), the implementation

for OpenRISC being in sysdeps/or1k/dl-machine.h.

In summary from top down:

- elf/rtld.c - implements

dl_main() the top level entry for the dynamic linker.

- elf/dl-open.c - function

dl_open_worker() calls _dl_relocate_object(), you may also recognize this from dlopen(3).

- elf/dl-reloc.c - function

_dl_relocate_object calls ELF_DYNAMIC_RELOCATE

elf/dynamic-link.h - defined macro ELF_DYNAMIC_RELOCATE calls elf_dynamic_do_Rel() via several macroself/do-rel.h - function elf_dynamic_do_Rel() calls elf_machine_rela()sysdeps/or1k/dl-machine.h - architecture specific function elf_machine_rela() implements dynamic relocation handling

It supports relocations for:

R_OR1K_NONE - do nothingR_OR1K_COPY - used to copy initial values from shared objects to process memory.R_OR1K_32 - a 32-bit valueR_OR1K_GLOB_DAT - aligned 32-bit values for GOT entriesR_OR1K_JMP_SLOT - aligned 32-bit values for PLT entriesR_OR1K_TLS_DTPMOD/R_OR1K_TLS_DTPOFF - for shared TLS GD GOT entriesR_OR1K_TLS_TPOFF - for shared TLS IE GOT entries

A snippet of the OpenRISC implementation of elf_machine_rela() can be seen

below. It is pretty straight forward.

/* Perform the relocation specified by RELOC and SYM (which is fully resolved).

MAP is the object containing the reloc. */

auto inline void

__attribute ((always_inline))

elf_machine_rela (struct link_map *map, const Elf32_Rela *reloc,

const Elf32_Sym *sym, const struct r_found_version *version,

void *const reloc_addr_arg, int skip_ifunc)

{

struct link_map *sym_map = RESOLVE_MAP (&sym, version, r_type);

Elf32_Addr value = SYMBOL_ADDRESS (sym_map, sym, true);

...

switch (r_type)

{

...

case R_OR1K_32:

/* Support relocations on mis-aligned offsets. */

value += reloc->r_addend;

memcpy (reloc_addr_arg, &value, 4);

break;

case R_OR1K_GLOB_DAT:

case R_OR1K_JMP_SLOT:

*reloc_addr = value + reloc->r_addend;

break;

...

}

}

Handling TLS

The complicated part of the runtime linker is how it handles TLS variables.

This is done in the following files and functions.

The reader can read through the initialization code which is pretty straight forward, except for the

macros. Like most GNU code the code relies heavily on untyped macros. These macros are defined

in the architecture specific implementation files. For OpenRISC this is:

From the previous article on TLS we have the

TLS data structure that looks as follows:

dtv[] [ dtv[0], dtv[1], dtv[2], .... ]

counter ^ | \

----/ / \________

/ V V

/------TCB-------\/----TLS[1]----\ /----TLS[2]----\

| pthread tcbhead | tbss tdata | | tbss tdata |

\----------------/\--------------/ \--------------/

^

|

TP-----/

The symbols and macros defined in sysdeps/or1k/nptl/tls.h are:

__thread_self - a symbol representing the current thread alwaysTLS_DTV_AT_TP - used throughout the TLS code to adjust offsetsTLS_TCB_AT_TP - used throughout the TLS code to adjust offsetsTLS_TCB_SIZE - used during init_tls() to allocate memory for TLSTLS_PRE_TCB_SIZE - used during init_tls() to allocate space for the pthread structINSTALL_DTV - used during initialization to update a new dtv pointer into the given tcbGET_DTV - gets dtv via the provided tcb pointerINSTALL_NEW_DTV - used during resizing to update the dtv into the current runtime __thread_selfTLS_INIT_TP - sets __thread_self this is the final step in init_tls()THREAD_DTV - gets dtv via _thread_selfTHREAD_SELF - get the pthread pointer via __thread_self

Implementations for OpenRISC are:

register tcbhead_t *__thread_self __asm__("r10");

#define TLS_DTV_AT_TP 1

#define TLS_TCB_AT_TP 0

#define TLS_TCB_SIZE sizeof (tcbhead_t)

#define TLS_PRE_TCB_SIZE sizeof (struct pthread)

#define INSTALL_DTV(tcbp, dtvp) (((tcbhead_t *) (tcbp))->dtv = (dtvp) + 1)

#define GET_DTV(tcbp) (((tcbhead_t *) (tcbp))->dtv)

#define TLS_INIT_TP(tcbp) ({__thread_self = ((tcbhead_t *)tcbp + 1); NULL;})

#define THREAD_DTV() ((((tcbhead_t *)__thread_self)-1)->dtv)

#define INSTALL_NEW_DTV(dtv) (THREAD_DTV() = (dtv))

#define THREAD_SELF \

((struct pthread *) ((char *) __thread_self - TLS_INIT_TCB_SIZE \

- TLS_PRE_TCB_SIZE))

Summary

We have looked at how symbols move from the Compiler, to Assembler, to Linker to

Runtime linker.

This has ended up being a long article to explain a rather complicated subject.

Let’s hope it helps provide a good reference for others who want to work on the

GNU toolchain in the future.

Further Reading

- GCC Passes - My blog entry on GCC passes

- bfdint - The BFD developer’s manual

- ldint - The LD developer’s manual

- LD and BFD Gist - Dump of notes I collected while working on this article.

19 Jan 2020

This is an ongoing series of posts on ELF Binary Relocations and Thread

Local Storage. This article covers only Thread Local Storage and assumes

the reader has had a primer in ELF Relocations, if not please start with

my previous article *ELF Binaries and Relocation Entries.

This is the second part in an illustrated 3 part series covering:

In the last article we covered ELF Binary internals and how relocation entries

are used to during link time to allow our programs to access symbols

(variables). However, what if we want a different variable instance for each

thread? This is where thread local storage (TLS) comes in.

In this article we will discuss how TLS works. Our outline:

As before, the examples in this article can be found in my tls-examples

project. Please check it out.

Thread Local Storage

Did you know that in C you can prefix variables with __thread to create

thread local variables?

Example

A thread local variable is a variable that will have a unique instance per thread.

Each time a new thread is created, the space required to store the thread local

variables is allocated.

TLS variables are stored in dynamic TLS sections.

TLS Sections

In the previous article we saw how variables were stored in the .data and

.bss sections. These are initialized once per program or library.

When we get to binaries that use TLS we will additionally have .tdata and

.tbss sections.

.tdata - static and non static initialized thread local variables.tbss - static and non static non-initialized thread local variables

These exist in a special TLS segment which

is loaded per thread. In the next article we will discuss more about how this

loading works.

TLS Data Structures

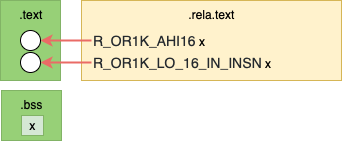

As we recall, to access data in .data and .bss sections simple code

sequences with relocation entries are used. These sequences set and add

registers to build pointers to our data. For example, the below sequence uses 2

relocations to compose a .bss section address into register r11.

Addr. Machine Code Assembly Relocations

0000000c <get_x_addr>:

c: 19 60 [00 00] l.movhi r11,[0] # c R_OR1K_AHI16 .bss

10: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

14: 9d 6b [00 00] l.addi r11,r11,[0] # 14 R_OR1K_LO_16_IN_INSN .bss

With TLS the code sequences to access our data will also build pointers to our

data, but they need to traverse the TLS data structures.

As the code sequence is read only and will be the same for each thread another

level of indirection is needed, this is provided by the Thread Pointer (TP).

The Thread Pointer points into a data structure that allows us to locate TLS

data sections. The TLS data structure includes:

- Thread Control Block (TCB)

- Dynamic Thread Vector (DTV)

- TLS Data Sections

These are illustrated as below:

dtv[] [ dtv[0], dtv[1], dtv[2], .... ]

counter ^ | \

----/ / \________

/ V V

/------TCB-------\/----TLS[1]----\ /----TLS[2]----\

| pthread tcbhead | tbss tdata | | tbss tdata |

\----------------/\--------------/ \--------------/

^

|

TP-----/

Thread Pointer (TP)

The TP is unique to each thread. It provides the starting point to the TLS data

structure.

- The TP points to the Thread Control Block

- On OpenRISC the TP is stored in

r10

- On x86_64 the TP is stored in

$fs

- This is the

*tls pointer passed to the

clone() system call when

using CLONE_SETTLS.

Thread Control Block (TCB)

The TCB is the head of the TLS data structure. The TCB consists of:

pthread - the pthread

struct for the current thread, contains tid etc. Located by TP - TCB size - Pthread sizetcbhead - the tcbhead_t struct, machine dependent, contains pointer to DTV. Located by TP - TCB size.

For OpenRISC tcbhead_t is defined in

sysdeps/or1k/nptl/tls.h as:

typedef struct {

dtv_t *dtv;

} tcbhead_t

dtv - is a pointer to the dtv array, points to entry dtv[1]

For x86_64 the tcbhead_t is defined in

sysdeps/x86_64/nptl/tls.h

as:

typedef struct

{

void *tcb; /* Pointer to the TCB. Not necessarily the

thread descriptor used by libpthread. */

dtv_t *dtv;

void *self; /* Pointer to the thread descriptor. */

int multiple_threads;

int gscope_flag;

uintptr_t sysinfo;

uintptr_t stack_guard;

uintptr_t pointer_guard;

unsigned long int vgetcpu_cache[2];

/* Bit 0: X86_FEATURE_1_IBT.

Bit 1: X86_FEATURE_1_SHSTK.

*/

unsigned int feature_1;

int __glibc_unused1;

/* Reservation of some values for the TM ABI. */

void *__private_tm[4];

/* GCC split stack support. */

void *__private_ss;

/* The lowest address of shadow stack, */

unsigned long long int ssp_base;

/* Must be kept even if it is no longer used by glibc since programs,

like AddressSanitizer, depend on the size of tcbhead_t. */

__128bits __glibc_unused2[8][4] __attribute__ ((aligned (32)));

void *__padding[8];

} tcbhead_t;

The x86_64 implementation includes many more fields including:

gscope_flag - Global Scope lock flags used by the runtime linker, for OpenRISC this is stored in pthread.stack_guard - The stack

guard canary stored in

the thread local area. For OpenRISC a global stack guard is stored in .bss.pointer_guard - The pointer

guard stored in the

thread local area. For OpenRISC a global pointer guard is stored in .bss.

Dynamic Thread Vector (DTV)

The DTV is an array of pointers to each TLS data section. The first entry in

the DTV array contains the generation counter. The generation counter is really

just the array size. The DTV can be dynamically resized as more TLS modules are loaded.

The dtv_t type is a union as defined below:

typedef struct {

void *val; // Aligned pointer to data/bss

void *to_free; // Unaligned pointer for free()

} dtv_pointer

typedef union {

int counter; // for entry 0

dtv_pointer pointer; // for all other entries

} dtv_t

Each dtv_t entry can be either a counter or a pointer. By convention the

first entry, dtv[0] is a counter and the rest are pointers.

Thread Local Storage (TLS)

The initial set of TLS data sections is allocated contiguous with the TCB. Additional TLS

data blocks will be allocated dynamically. There will be one entry for each

loaded module, the first module being the current program. For dynamic

libraries it is lazily initialized per thread.

Local (or TLS[1])

tbss - the .tbss section for the current thread from the current

processes ELF binary.tdata - the .tdata section for the current thread from the current

processes ELF binary.

TLS[2]

tbss - the .tbss section for variables defined in the first shared library loaded by the current processtdata - the .tdata section for variables defined in the first shared library loaded by the current process

The __tls_get_addr() function

The __tls_get_addr() function can be used at any time to traverse the TLS data

structure and return a variable’s address. The function is given a pointer to

an architecture specific argument tls_index.

- The argument contains 2 pieces of data:

- The module index -

0 for the current process, 1 for the first loaded shared

library etc.

- The data offset - the offset of the variable in the

TLS data section

- Internally

__tls_get_addr uses TP to located the TLS data structure

- The function returns the address of the variable we want to access

For static builds the implementation is architecture dependant and defined in

OpenRISC

sysdeps/or1k/libc-tls.c

as:

__tls_get_addr (tls_index *ti)

{

dtv_t *dtv = THREAD_DTV ();

return (char *) dtv[1].pointer.val + ti->ti_offset;

}

Note for for static builds the module index can be hard coded to 1 as there

will always be only one module.

For dynamically linked programs the implementation is defined as part of the

runtime dynamic linker in

elf/dl-tls.c

as:

void *

__tls_get_addr (GET_ADDR_ARGS)

{

dtv_t *dtv = THREAD_DTV ();

if (__glibc_unlikely (dtv[0].counter != GL(dl_tls_generation)))

return update_get_addr (GET_ADDR_PARAM);

void *p = dtv[GET_ADDR_MODULE].pointer.val;

if (__glibc_unlikely (p == TLS_DTV_UNALLOCATED))

return tls_get_addr_tail (GET_ADDR_PARAM, dtv, NULL);

return (char *) p + GET_ADDR_OFFSET;

}

Here several macros are used so it’s a bit hard to follow but there are:

THREAD_DTV - uses TP to get the pointer to the DTV array.GET_ADDR_ARGS - short for tls_index* tiGET_ADDR_PARAM - short for tiGET_ADDR_MODULE - short for ti->ti_moduleGET_ADDR_OFFSET - short for ti->ti_offset

TLS Access Models

As one can imagine, traversing the TLS data structures when accessing each variable

could be slow. For this reason there are different TLS access models that the

compiler can choose to minimize variable access overhead.

Global Dynamic

The Global Dynamic (GD), sometimes called General Dynamic, access model is the

slowest access model which will traverse the entire TLS data structure for each

variable access. It is used for accessing variables in dynamic shared

libraries.

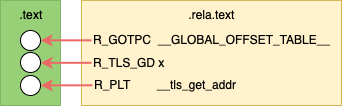

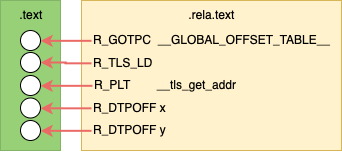

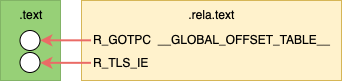

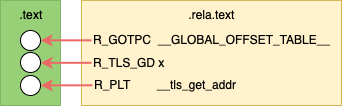

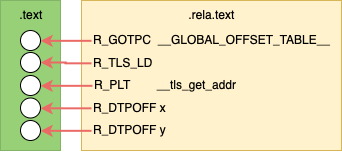

Before Linking

Not counting relocations for the PLT and GOT entries; before linking the .text

contains 1 placeholder for a GOT offset. This GOT entry will contain the

arguments to __tls_get_addr.

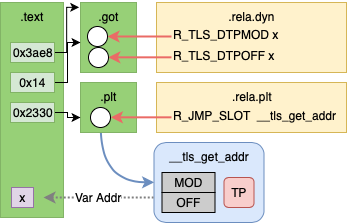

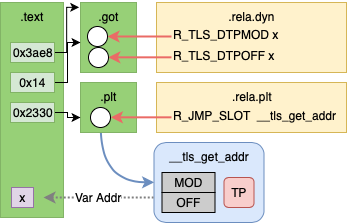

After Linking

After linking there will be 2 relocation entries in the GOT to be resolved by

the dynamic linker. These are R_TLS_DTPMOD, the TLS module index, and

R_TLS_DTPOFF, the offset of the variable into the TLS module.

Example

File: tls-gd.c

extern __thread int x;

int* get_x_addr() {

return &x;

}

Code Sequence (OpenRISC)

tls-gd.o: file format elf32-or1k

Disassembly of section .text:

0000004c <get_x_addr>:

4c: 18 60 [00 00] l.movhi r3,[0] # 4c: R_OR1K_TLS_GD_HI16 x

50: 9c 21 ff f8 l.addi r1,r1,-8

54: a8 63 [00 00] l.ori r3,r3,[0] # 54: R_OR1K_TLS_GD_LO16 x

58: d4 01 80 00 l.sw 0(r1),r16

5c: d4 01 48 04 l.sw 4(r1),r9

60: 04 00 00 02 l.jal 68 <get_x_addr+0x1c>

64: 1a 00 [00 00] l.movhi r16,[0] # 64: R_OR1K_GOTPC_HI16 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_-0x4

68: aa 10 [00 00] l.ori r16,r16,[0] # 68: R_OR1K_GOTPC_LO16 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

6c: e2 10 48 00 l.add r16,r16,r9

70: 04 00 [00 00] l.jal [0] # 70: R_OR1K_PLT26 __tls_get_addr

74: e0 63 80 00 l.add r3,r3,r16

78: 85 21 00 04 l.lwz r9,4(r1)

7c: 86 01 00 00 l.lwz r16,0(r1)

80: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

84: 9c 21 00 08 l.addi r1,r1,8

Code Sequence (x86_64)

tls-gd.o: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000020 <get_x_addr>:

20: 48 83 ec 08 sub $0x8,%rsp

24: 66 48 8d 3d [00 00 00 00] lea [0](%rip),%rdi # 28 R_X86_64_TLSGD x-0x4

2c: 66 66 48 e8 [00 00 00 00] callq [0] # 30 R_X86_64_PLT32 __tls_get_addr-0x4

34: 48 83 c4 08 add $0x8,%rsp

38: c3 retq

Local Dynamic

The Local Dynamic (LD) access model is an optimization for Global Dynamic where

multiple variables may be accessed from the same TLS module. Instead of

traversing the TLS data structure for each variable, the TLS data section address

is loaded once by calling __tls_get_addr with an offset of 0. Next, variables

can be accessed with individual offsets.

Local Dynamic is not supported on OpenRISC yet.

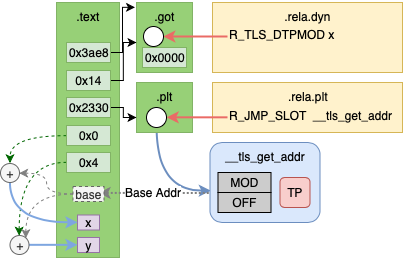

Before Linking

Not counting relocations for the PLT and GOT entries; before linking the .text

contains 1 placeholder for a GOT offset and 2 placeholders for the TLS offsets.

This GOT entry will contain the arguments to __tls_get_addr.

The TLD offsets will be the offsets to our variables in the TLD data section.

After Linking

After linking there will be 1 relocation entry in the GOT to be resolved by

the dynamic linker. This is R_TLS_DTPMOD, the TLS module index, the offset

will be 0x0.

Example

File: tls-ld.c

static __thread int x;

static __thread int y;

int sum() {

return x + y;

}

Code Sequence (x86_64)

tls-ld.o: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000030 <sum>:

30: 48 83 ec 08 sub $0x8,%rsp

34: 48 8d 3d [00 00 00 00] lea [0](%rip),%rdi # 37 R_X86_64_TLSLD x-0x4

3b: e8 [00 00 00 00] callq [0] # 3c R_X86_64_PLT32 __tls_get_addr-0x4

40: 8b 90 [00 00 00 00] mov [0](%rax),%edx # 42 R_X86_64_DTPOFF32 x

46: 03 90 [00 00 00 00] add [0](%rax),%edx # 48 R_X86_64_DTPOFF32 y

4c: 48 83 c4 08 add $0x8,%rsp

50: 89 d0 mov %edx,%eax

52: c3 retq

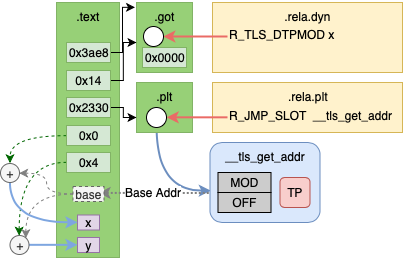

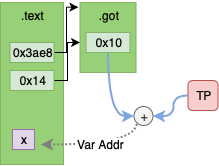

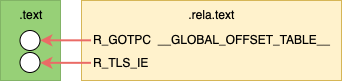

Initial Exec

The Initial Exec (IE) access model does not require traversing the TLS data

structure. It requires that the compiler knows that offset from the TP to the

variable can be computed during link time.

As Initial Exec does not require calling __tls_get_addr is is more efficient

compared the GD and LD access.

Before Linking

Text contains a placeholder for the got address of the offset. Not counting

relocation entry for the GOT; before linking the .text contains 1 placeholder

for a GOT offset. This GOT entry will contain the TP offset to the variable.

After Linking

After linking there will be no remaining relocation entries. The .text section

contains the actual GOT offset and the GOT entry will contain the TP offset

to the variable.

Example

File: tls-ie.c

Initial exec C code will be the same as global dynamic, however IE access will

be chosen when static compiling.

extern __thread int x;

int* get_x_addr() {

return &x;

}

Code Sequence (OpenRISC)

00000038 <get_x_addr>:

38: 9c 21 ff fc l.addi r1,r1,-4

3c: 1a 20 [00 00] l.movhi r17,[0x0] # 3c: R_OR1K_TLS_IE_AHI16 x

40: d4 01 48 00 l.sw 0(r1),r9

44: 04 00 00 02 l.jal 4c <get_x_addr+0x14>

48: 1a 60 [00 00] l.movhi r19,[0x0] # 48: R_OR1K_GOTPC_HI16 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_-0x4

4c: aa 73 [00 00] l.ori r19,r19,[0x0] # 4c: R_OR1K_GOTPC_LO16 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

50: e2 73 48 00 l.add r19,r19,r9

54: e2 31 98 00 l.add r17,r17,r19

58: 85 71 [00 00] l.lwz r11,[0](r17) # 58: R_OR1K_TLS_IE_LO16 x

5c: 85 21 00 00 l.lwz r9,0(r1)

60: e1 6b 50 00 l.add r11,r11,r10

64: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

68: 9c 21 00 04 l.addi r1,r1,4

Code Sequence (x86_64)

0000000000000010 <get_x_addr>:

10: 48 8b 05 [00 00 00 00] mov 0x0(%rip),%rax # 13: R_X86_64_GOTTPOFF x-0x4

17: 64 48 03 04 25 00 00 00 00 add %fs:0x0,%rax

20: c3 retq

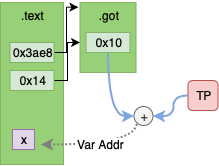

Local Exec

The Local Exec (LD) access model does not require traversing the TLS data

structure or a GOT entry. It is chosen by the compiler when accessing file

local variables in the current program.

The Local Exec access model is the most efficient.

Before Linking

Before linking the .text section contains one relocation entry for a TP

offset.

After Linking

After linking the .text section contains the value of the TP offset.

Example

File: tls-le.c

In the Local Exec example the variable x is local, it is not extern.

static __thread int x;

int * get_x_addr() {

return &x;

}

Code Sequence (OpenRISC)

00000010 <get_x_addr>:

10: 19 60 [00 00] l.movhi r11,[0x0] # 10: R_OR1K_TLS_LE_AHI16 .LANCHOR0

14: e1 6b 50 00 l.add r11,r11,r10

18: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

1c: 9d 6b [00 00] l.addi r11,r11,[0] # 1c: R_OR1K_TLS_LE_LO16 .LANCHOR0

Code Sequence (x86_64)

0000000000000010 <get_x_addr>:

10: 64 48 8b 04 25 00 00 00 00 mov %fs:0x0,%rax

19: 48 05 [00 00 00 00] add $0x0,%rax # 1b: R_X86_64_TPOFF32 x

1f: c3 retq

Linker Relaxation

As some TLS access methods are more efficient than others we would like to

choose the best method for each variable access. However, we sometimes don’t know

where a variable will come from until link time.

On some architectures the linker will rewrite the TLS access code sequence to

change to a more efficient access model, this is called relaxation.

One type of relaxation performed by the linker is GD to IE relaxation. During compile

time GD relocation may be chosen for extern variables. However, during link time

the variable may be found in the same module i.e. not a shared object which would require

GD access. In this case the access model can be changed to IE.

That’s pretty cool.

The architecture I work on OpenRISC does not support any

of this yet, it requires changes to the compiler and linker. The compiler needs

to be updated to mark sections of the output .text that can be rewritten

(often with added NOP codes). The linker needs to be updated to know how to

identify the relaxation opportunity and perform it.

Summary

In this article we have covered how TLS variables are accessed per thread via

the TLS data structure. Also, we saw how different TLS access models provide

varying levels of efficiency.

In the next article we will look more into how this is implemented in GCC, the

linker and the GLIBC runtime dynamic linker.

Further Reading

29 Nov 2019

Recently I have been working on getting the OpenRISC glibc

port ready for upstreaming. Part of this work has been to run the glibc

testsuite and get the tests to pass. The glibc testsuite

has a comprehensive set of linker and runtime relocation tests.

In order to fix issues with tests I had to learn more than I did before about ELF Relocations

, Thread Local Storage and the binutils linker implementation in BFD. There is a lot of

documentation available, but it’s a bit hard to follow as it assumes certain

knowledge, for example have a look at the Solaris Linker and Libraries

section on relocations. In this article I will try to fill in those gaps.

This will be an illustrated 3 part series covering

All of the examples in this article can be found in my tls-examples

project. Please check it out.

On Linux, you can download it and make it with your favorite toolchain.

By default it will cross compile using an openrisc toolchain.

This can be overridden with the CROSS_COMPILE variable.

For example, to build for your current host.

$ git clone git@github.com:stffrdhrn/tls-examples.git

$ make CROSS_COMPILE=

gcc -fpic -c -o tls-gd-dynamic.o tls-gd.c -Wall -O2 -g

gcc -fpic -c -o nontls-dynamic.o nontls.c -Wall -O2 -g

...

objdump -dr x-static.o > x-static.S

objdump -dr xy-static.o > xy-static.S

Now we can get started.

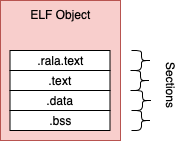

ELF Segments and Sections

Before we can talk about relocations we need to talk a bit about what makes up

ELF binaries.

This is a prerequisite as relocations and TLS are part of ELF binaries. There

are a few basic ELF binary types:

- Objects (

.o) - produced by a compiler, contains a collection of sections, also call relocatable files.

- Program - an executable program, contains sections grouped into segments.

- Shared Objects (

.so) - a program library, contains sections grouped into segments.

- Core Files - core dump of program memory, these are also ELF binaries

Here we will discuss Object Files and Program Files.

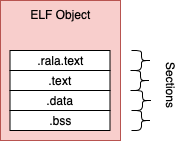

An ELF Object

The compiler generates object files, these contain sections of binary data and

these are not executable.

The object file produced by gcc

generally contains .rela.text, .text, .data and .bss sections.

.rela.text - a list of relocations against the .text section.text - contains compiled program machine code.data - static and non static initialized variable values.bss - static and non static non-initialized variables

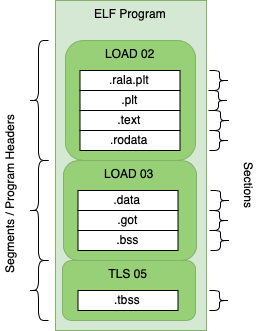

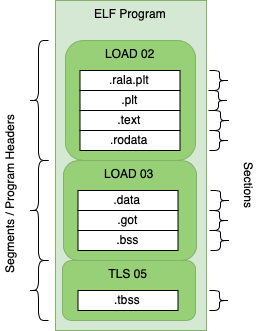

An ELF Program

ELF binaries are made of sections and segments.

A segment contains a group of sections and the segment defines how the data should

be loaded into memory for program execution.

Each segment is mapped to program memory by the kernel when a process is created. Program files contain

most of the same sections as objects but there are some differences.

.text - contains executable program code, there is no .rela.text section.got - the global offset table used to access variables, created during link time. May be populated during runtime.

Looking at ELF binaries (readelf)

The readelf tool can help inspect elf binaries.

Some examples:

Reading Sections of an Object File

Using the -S option we can read sections from an elf file.

As we can see below we have the .text, .rela.text, .bss and many other

sections.

$ readelf -S tls-le-static.o

There are 20 section headers, starting at offset 0x604:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 00000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 00000000 000034 000020 00 AX 0 0 4

[ 2] .rela.text RELA 00000000 0003f8 000030 0c I 17 1 4

[ 3] .data PROGBITS 00000000 000054 000000 00 WA 0 0 1

[ 4] .bss NOBITS 00000000 000054 000000 00 WA 0 0 1

[ 5] .tbss NOBITS 00000000 000054 000004 00 WAT 0 0 4

[ 6] .debug_info PROGBITS 00000000 000054 000074 00 0 0 1

[ 7] .rela.debug_info RELA 00000000 000428 000084 0c I 17 6 4

[ 8] .debug_abbrev PROGBITS 00000000 0000c8 00007c 00 0 0 1

[ 9] .debug_aranges PROGBITS 00000000 000144 000020 00 0 0 1

[10] .rela.debug_arang RELA 00000000 0004ac 000018 0c I 17 9 4

[11] .debug_line PROGBITS 00000000 000164 000087 00 0 0 1

[12] .rela.debug_line RELA 00000000 0004c4 00006c 0c I 17 11 4

[13] .debug_str PROGBITS 00000000 0001eb 00007a 01 MS 0 0 1

[14] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 000265 00002b 01 MS 0 0 1

[15] .debug_frame PROGBITS 00000000 000290 000030 00 0 0 4

[16] .rela.debug_frame RELA 00000000 000530 000030 0c I 17 15 4

[17] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 0002c0 000110 10 18 15 4

[18] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 0003d0 000025 00 0 0 1

[19] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 000560 0000a1 00 0 0 1

Reading Sections of a Program File

Using the -S option on a program file we can also read the sections. The file

type does not matter as long as it is an ELF we can read the sections.

As we can see below there is no longer a rela.text section, but we have others

including the .got section.

$ readelf -S tls-le-static

There are 31 section headers, starting at offset 0x32e8fc:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 00000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 000020d4 0000d4 080304 00 AX 0 0 4

[ 2] __libc_freeres_fn PROGBITS 000823d8 0803d8 001118 00 AX 0 0 4

[ 3] .rodata PROGBITS 000834f0 0814f0 01544c 00 A 0 0 4

[ 4] __libc_subfreeres PROGBITS 0009893c 09693c 000024 00 A 0 0 4

[ 5] __libc_IO_vtables PROGBITS 00098960 096960 0002f4 00 A 0 0 4

[ 6] __libc_atexit PROGBITS 00098c54 096c54 000004 00 A 0 0 4

[ 7] .eh_frame PROGBITS 00098c58 096c58 0027a8 00 A 0 0 4

[ 8] .gcc_except_table PROGBITS 0009b400 099400 000089 00 A 0 0 1

[ 9] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 0009b48c 09948c 000020 00 A 0 0 4

[10] .tdata PROGBITS 0009dc28 099c28 000010 00 WAT 0 0 4

[11] .tbss NOBITS 0009dc38 099c38 000024 00 WAT 0 0 4

[12] .init_array INIT_ARRAY 0009dc38 099c38 000004 04 WA 0 0 4

[13] .fini_array FINI_ARRAY 0009dc3c 099c3c 000008 04 WA 0 0 4

[14] .data.rel.ro PROGBITS 0009dc44 099c44 0003bc 00 WA 0 0 4

[15] .data PROGBITS 0009e000 09a000 000de0 00 WA 0 0 4

[16] .got PROGBITS 0009ede0 09ade0 000064 04 WA 0 0 4

[17] .bss NOBITS 0009ee44 09ae44 000bec 00 WA 0 0 4

[18] __libc_freeres_pt NOBITS 0009fa30 09ae44 000014 00 WA 0 0 4

[19] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 09ae44 00002a 01 MS 0 0 1

[20] .debug_aranges PROGBITS 00000000 09ae6e 002300 00 0 0 1

[21] .debug_info PROGBITS 00000000 09d16e 0fd048 00 0 0 1

[22] .debug_abbrev PROGBITS 00000000 19a1b6 0270ca 00 0 0 1

[23] .debug_line PROGBITS 00000000 1c1280 0ce95c 00 0 0 1

[24] .debug_frame PROGBITS 00000000 28fbdc 0063bc 00 0 0 4

[25] .debug_str PROGBITS 00000000 295f98 011e35 01 MS 0 0 1

[26] .debug_loc PROGBITS 00000000 2a7dcd 06c437 00 0 0 1

[27] .debug_ranges PROGBITS 00000000 314204 00c900 00 0 0 1

[28] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 320b04 0075d0 10 29 926 4

[29] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 3280d4 0066ca 00 0 0 1

[30] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 32e79e 00015c 00 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

p (processor specific)

Reading Segments from a Program File

Using the -l option on a program file we can read the segments.

Notice how segments map from file offsets to memory offsets and alignment.

The two different LOAD type segments are segregated by read only/execute and read/write.

Each section is also mapped to a segment here. As we can see .text is in the first LOAD` segment

which is executable as expected.

$ readelf -l tls-le-static

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x2104

There are 5 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

LOAD 0x000000 0x00002000 0x00002000 0x994ac 0x994ac R E 0x2000

LOAD 0x099c28 0x0009dc28 0x0009dc28 0x0121c 0x01e1c RW 0x2000

NOTE 0x09948c 0x0009b48c 0x0009b48c 0x00020 0x00020 R 0x4

TLS 0x099c28 0x0009dc28 0x0009dc28 0x00010 0x00034 R 0x4

GNU_RELRO 0x099c28 0x0009dc28 0x0009dc28 0x003d8 0x003d8 R 0x1

Section to Segment mapping:

Segment Sections...

00 .text __libc_freeres_fn .rodata __libc_subfreeres __libc_IO_vtables __libc_atexit .eh_frame .gcc_except_table .note.ABI-tag

01 .tdata .init_array .fini_array .data.rel.ro .data .got .bss __libc_freeres_ptrs

02 .note.ABI-tag

03 .tdata .tbss

04 .tdata .init_array .fini_array .data.rel.ro

Reading Segments from an Object File

Using the -l option with an object file does not work as we can see below.

readelf -l tls-le-static.o

There are no program headers in this file.

Relocation entries

As mentioned an object file by itself is not executable. The main reason is that

there are no program headers as we just saw. Another reason is that

the .text section still contains relocation entries (or placeholders) for the

addresses of variables located in the .data and .bss sections.

These placeholders will just be 0 in the machine code. So, if we tried to run

the machine code in an object file we would end up with Segmentation faults (SEGV).

A relocation entry is a placeholder that is added by the compiler or linker when

producing ELF binaries.

The relocation entries are to be filled in with addresses pointing to data.

Relocation entries can be made in code such as the .text section or in data

sections like the .got section. For example:

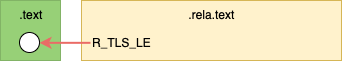

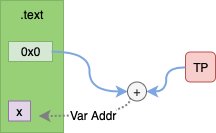

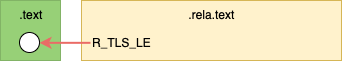

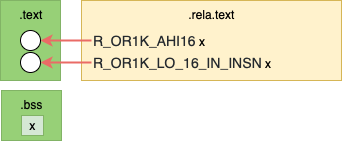

Resolving Relocations

The diagram above shows relocation entries as white circles.

Relocation entries may be filled or resolved at link-time or dynamically during execution.

Link time relocations

- Place holders are filled in when ELF object files are linked by the linker to create executables or libraries

- For example, relocation entries in

.text sections

Dynamic relocations

- Place holders is filled during runtime by the dynamic linker. i.e. Procedure Link Table

- For example, relocation entries added to

.got and .plt sections which link

to shared objects.

Note: Statically built binaries do not have any dynamic relocations and are not

loaded with the dynamic linker.

In general link time relocations are used to fill in relocation entries in code.

Dynamic relocations fill in relocation entries in data sections.

Listing Relocation Entries

A list of relocations in a ELF binary can printed using readelf with

the -r options.

Output of readelf -r tls-gd-dynamic.o

Relocation section '.rela.text' at offset 0x530 contains 10 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym.Value Sym. Name + Addend

00000000 00000f16 R_OR1K_TLS_GD_HI1 00000000 x + 0

00000008 00000f17 R_OR1K_TLS_GD_LO1 00000000 x + 0

00000020 0000100c R_OR1K_GOTPC_HI16 00000000 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ - 4

00000024 0000100d R_OR1K_GOTPC_LO16 00000000 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ + 0

0000002c 00000d0f R_OR1K_PLT26 00000000 __tls_get_addr + 0

...

The relocation entry list explains how to and where to apply the relocation entry.

It contains:

Offset - the location in the binary that needs to be updatedInfo - the encoded value containing the Type, Sym and Addend, which is

broken down to:

Type - the type of relocation (the formula for what is to be performed is defined in the

linker)Sym. Value - the address value (if known) of the symbol.Sym. Name - the name of the symbol (variable name) that this relocation needs to find

during link time.

Addend - a value that needs to be added to the derived symbol address.

This is used to with arrays (i.e. for a relocation referencing a[14] we would have Sym. Name a and an Addend of the data size of a times 14)

Example

File: nontls.c

In the example below we have a simple variable and a function to access it’s

address.

static int x;

int* get_x_addr() {

return &x;

}

Let’s see what happens when we compile this source.

The steps to compile and link can be found in the tls-examples project hosting

the source examples.

Before Linking

The diagram above shows relocations in the resulting object file as white circles.

In the actual output below we can see that access to the variable x is

referenced by a literal 0 in each instruction. These are highlighted with

square brackets [] below for clarity.

These empty parts of the .text section are relocation entries.

Addr. Machine Code Assembly Relocations

0000000c <get_x_addr>:

c: 19 60 [00 00] l.movhi r11,[0] # c R_OR1K_AHI16 .bss

10: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

14: 9d 6b [00 00] l.addi r11,r11,[0] # 14 R_OR1K_LO_16_IN_INSN .bss

The function get_x_addr will return the address of variable x.

We can look at the assembly instruction to understand how this is done. Some background

of the OpenRISC ABI.

- Registers are 32-bit.

- Function return values are placed in register

r11.

- To return from a function we jump to the address in the link register

r9.

- OpenRISC has a branch delay slot, meaning the address after a branch it executed

before the branch is taken.

Now, lets break down the assembly:

l.movhi - move the value [0] into high bits of register r11, clearing the lower bits.l.addi - add the value in register r11 to the value [0] and store the results in r11.l.jr - jump to the address in r9

This constructs a 32-bit value out of 2 16-bit values.

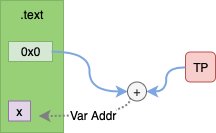

After Linking

The diagram above shows the relocations have been replaced with actual values.

As we can see from the linker output the places in the machine code that had relocation place holders

are now replaced with values. For example 1a 20 00 00 has become 1a 20 00 0a.

00002298 <get_x_addr>:

2298: 19 60 00 0a l.movhi r11,0xa

229c: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

22a0: 9d 6b ee 60 l.addi r11,r11,-4512

If we calculate 0xa << 16 + -4512 (fee60) we see get 0009ee60. That is the

same location of x within our binary. This we can check with readelf -s

which lists all symbols.

$ readelf -s nontls-static | grep ' x'

42: 0009ee60 4 OBJECT LOCAL DEFAULT 17 x

Types of Relocations

As we saw above, a simple program resulted in 2 different relocation entries just to compose the address of 1 variable.

We saw:

R_OR1K_AHI16R_OR1K_LO_16_IN_INSN

The need for different relacation types comes from the different requirements for the

relocation. Processing of a relocation involves usually a very simple transform

, each relocation defines a different transform. The components of the relocation

definition are:

- Input The input of a relocation formula is always the Symbol Address who’s absolute value is unknown at compile time. But

there may also be other input variables to the formula including:

- Program Counter The absolute address of the machine code address being updated

- Addend The addend from the relocation entry discussed above in the Listing Relocation Entries section

- Formula How the input is manipulated to derive the output value. For example shift right 16 bits.

- Bit-Field Specifies which bits at the output address need to be updated.

To be more specific about the above relocations we have:

| Relocation Type |

Bit-Field |

Formula |

R_OR1K_AHI16 |

simm16 |

S >> 16 |

R_OR1K_LO_16_IN_INSN |

simm16 |

S && 0xffff |

The Bit-Field described above is simm16 which means update the lower 16-bits

of the 32-bit value at the output offset and do not disturb the upper 16-bits.

+----------+----------+

| | simm16 |

| 31 16 | 15 0 |

+----------+----------+

There are many other Relocation Types with difference Bit-Fields and Formulas.

These use different methods based on what each instruction does, and where each instruction

encodes its immediate value.

For full listings refer to architecture manuals.

Take a look and see if you can understand how to read these now.

Summary

In this article we have discussed what ELF binaries are and how they can be read.

We have talked about how from compilation to linking to runtime, relocation entries

are used to communicate which parts of a program remain to be resolved. We

then discussed how relocation types provide a formula and bit-mask for updating

the places in ELF binaries that need to be filled in.

In the next article we will discuss how Thread Local Storage works, both link-time

and runtime relocation entries play big part in how TLS works.

Further Reading

21 Oct 2019

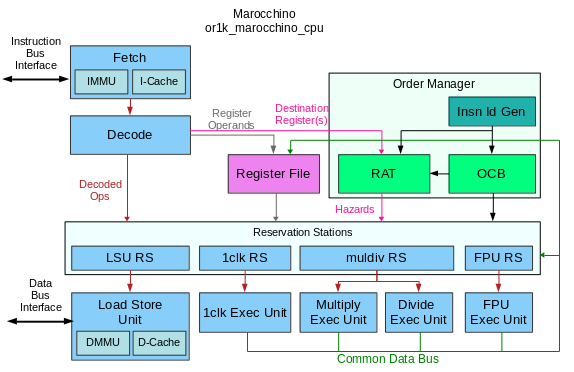

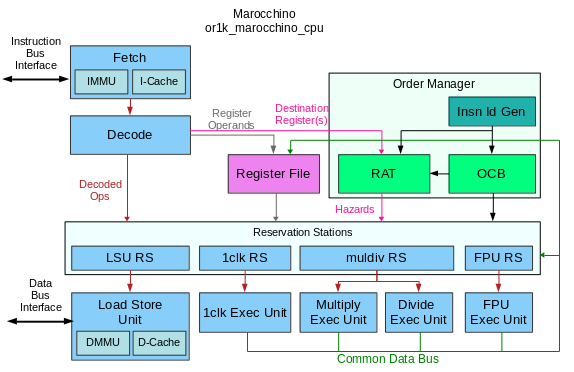

This is an ongoing series of posts on the Marocchino CPU, an open source out-of-order

OpenRISC cpu. In this series we are reviewing the

Marocchino and it’s architecture. If you haven’t already I suggest you start of

by reading the intro in Marocchino in Action.

In the last article, Marocchino Instruction Pipeline we discussed the

architecture of the CPU. In this article let’s look at how Marocchino achieves

out-of-order execution using the Tomasulo algorithm.

Achieving Out-of-Order Execution

In a traditional pipelined CPU the goal is retire one instruction

per clock cycle. Any pipeline stall means an execution clock cycle will be lost.

One method for reducing the affect of pipeline stalls is instruction parallelization. In 1993

the Intel Pentium

processor was one of the first consumer CPUs to achieve this with it’s dual U

and V integer pipelines.

The pentium U and V pipelines require certain coding

techniques to take full

advantage. Achieving more parallelism requires more sophisticated data hazard

detection and instruction scheduling. Introduced with the IBM System/360 in the

60’s by Robert Tomasulo, the Tomosulo Algorithm provides the building blocks to

allow for multiple instruction execution parallelism. Generally speaking no special programming is needed to

take advantage of instruction parallelism on a processor implementing Tomasulo

algorithm.

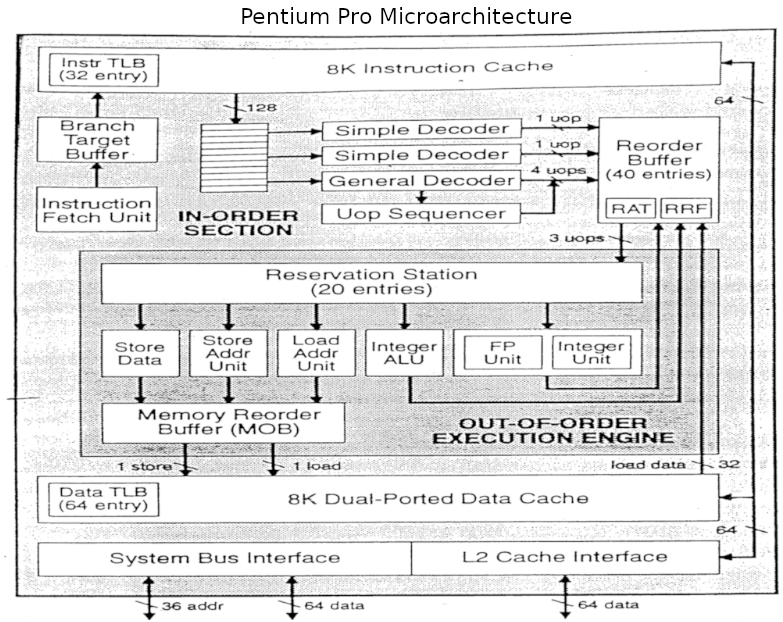

Though the technique of out-of-order CPU execution with Tomasulo’s algorithm had

been designed in the 60’s it did not make its way into popular consumer hardware

until the Pentium Pro in the 1995.

Further Pentium revisions such as the Pentium III, Pentium 4 and Core

architectures are based on this same architecture. Understanding

this architecture is a key to understanding modern CPUs.

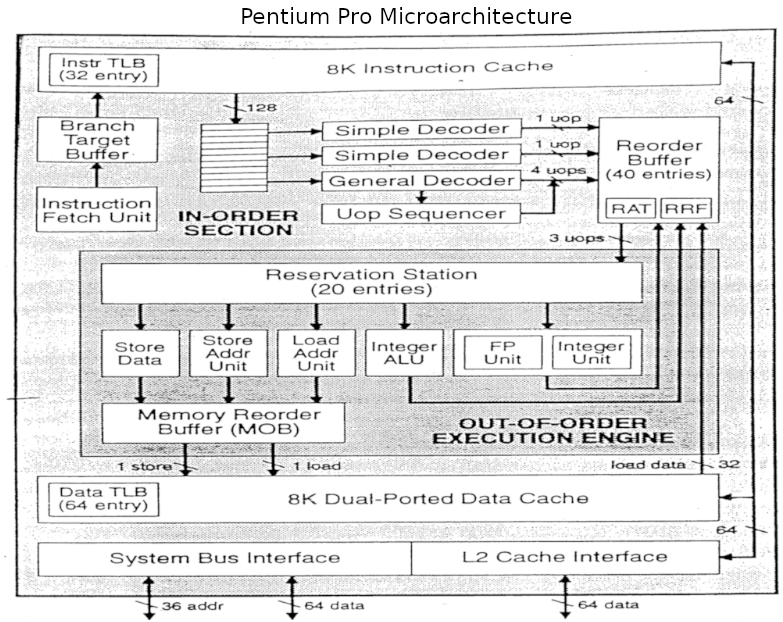

In this article we will point out comparisons between the Marocchino and Pentium pro

who’s architecture can be seen in the below diagram.

The Marocchino implements the Tomasulo algorithm in a CPU that can be synthesized

and run on an FPGA. Let’s dive into the implementation by breaking down the

building blocks used in Tomasulo’s algorithm and how they have been implemented in

Marocchino.

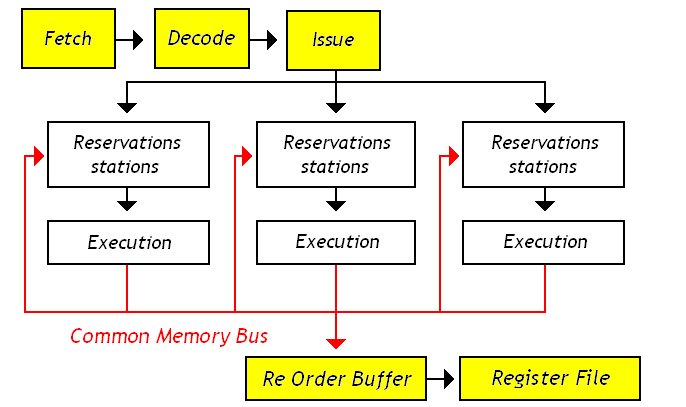

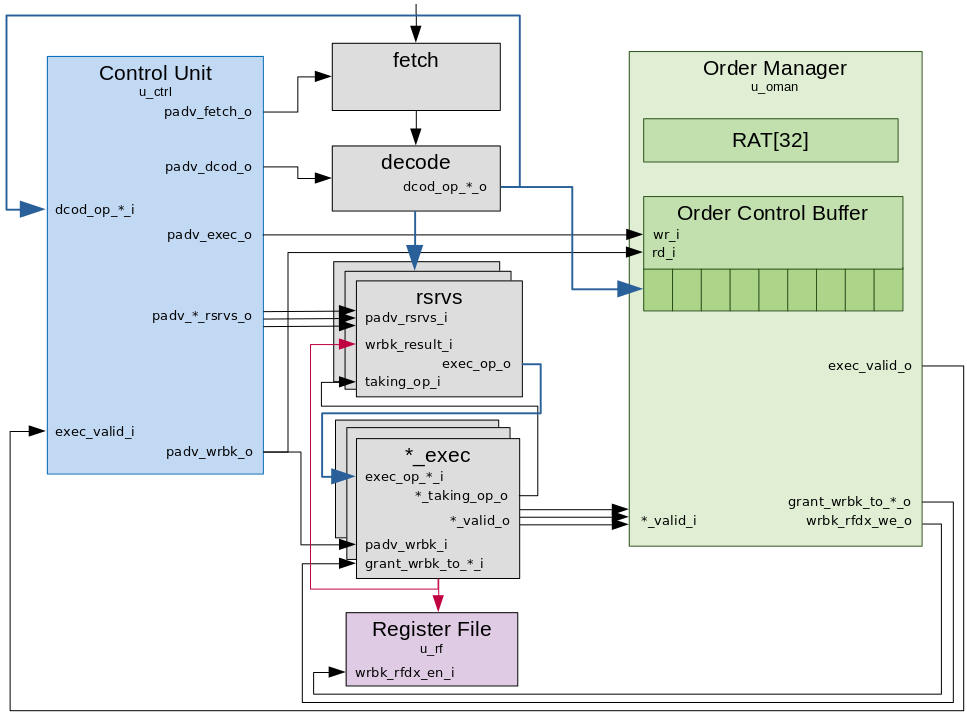

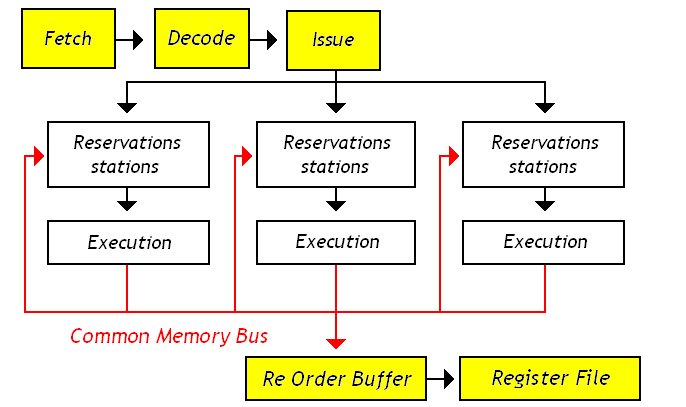

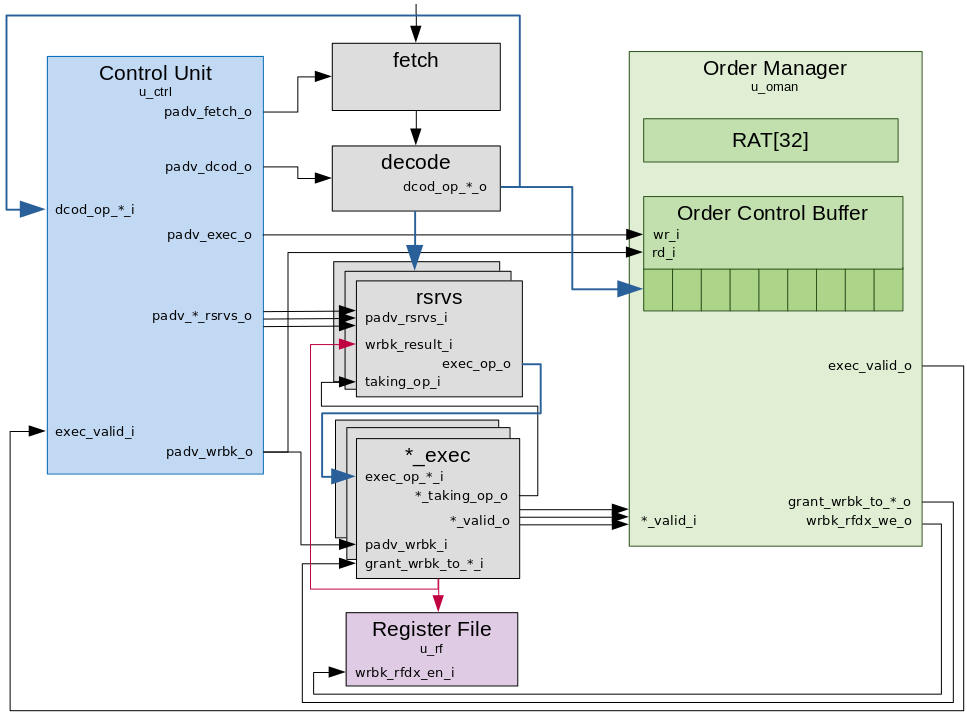

Tomasulo Building blocks

Besides the basic CPU modules like Instruction Fetch, Decode and Register File,

the building blocks that are used in the Tomasulo algorithm are as follows:

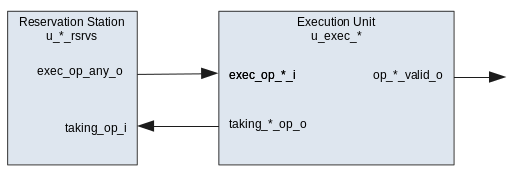

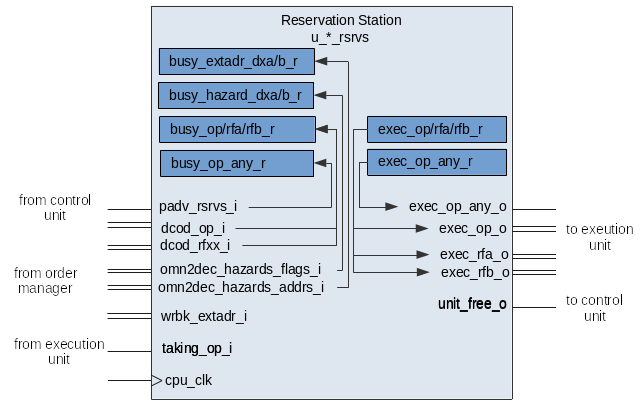

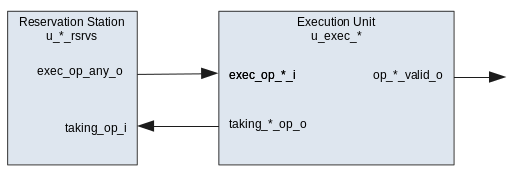

- Reservation Station - A

queue where decoded instructions are placed before they can be

executed. Instructions are placed in the queue with their decoded operation

and available arguments. If any arguments are not available the reservation

station will wait until the arguments are available before executing.

- Execution Units - The execution units include the Arithmetic

Logic Unit (ALU), Memory Load/Store Unit or FPU is responsible for performing

the instruction operation.

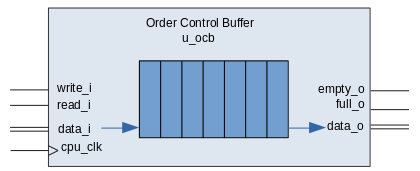

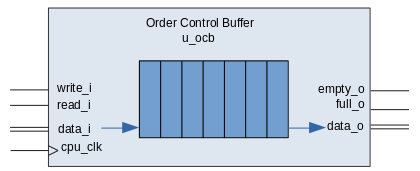

- Re-order Buffer (ROB) - A ring

buffer which manages the order in which instructions are retired. In Marocchino

the implementation is slightly simplified and called the Order Control Buffer (OCB).

- Instruction Ids - As an instruction is queued into the ROB, or OCB in Marocchino

it is assigned an Instruction Id which is used to track the instruction in different

components in Marocchino code this is called the

extaddr.