13 Jan 2026

This is the story of figuring out why OpenRISC Linux was no longer booting on FPGA boards.

In July 2025 we received a bug report: #168 mor1kx pipeline is stuck in dualcore iverilog RTL simulation.

The report showed a hang on the second CPU of a custom

multicore platform. The

CPU cores that we use in FPGA based

SoCs are highly configurable,

we can change cache sizes, MMU set sizes, memory synchronization strategies and

other settings. Our first step were to ensure that these settings were

correct. After some initial discussions and adjustments the user was able to

make progress, but Linux booted and hung with an error. The following is a

snippet of the boot log:

[ 72.530000] Run /init as init process

[ 95.470000] rcu: INFO: rcu_sched detected stalls on CPUs/tasks:

[ 95.470000] rcu: (detected by 0, t=2102 jiffies, g=-1063, q=3 ncpus=2)

[ 95.470000] rcu: All QSes seen, last rcu_sched kthread activity 2088 (-20453--22541), jiffies_till_next_fqs=1, root ->qsmask 0x0

[ 95.470000] rcu: rcu_sched kthread timer wakeup didn't happen for 2087 jiffies! g-1063 f0x2 RCU_GP_WAIT_FQS(5) ->state=0x200

[ 95.470000] rcu: Possible timer handling issue on cpu=1 timer-softirq=194

[ 95.470000] rcu: rcu_sched kthread starved for 2088 jiffies! g-1063 f0x2 RCU_GP_WAIT_FQS(5) ->state=0x200 ->cpu=1

[ 95.470000] rcu: Unless rcu_sched kthread gets sufficient CPU time, OOM is now expected behavior.

[ 95.470000] rcu: RCU grace-period kthread stack dump:

[ 95.470000] task:rcu_sched state:R stack:0 pid:12 tgid:12 ppid:2 task_flags:0x208040 flags:0x00000000

[ 95.470000] Call trace:

[ 95.470000] [<(ptrval)>] 0xc00509a4

[ 95.470000] [<(ptrval)>] 0xc0050a04

In the above log we see an RCU

stall warning indicating that CPU 1 running but not making progressing and is

likely stuck in a tight loop. We can also see that the CPUs are both running

but hanging. It took until December 2025, 5 months, to locate and fix the bug.

In this article we will discuss how we debugged and solved this issue.

Reproducing the issue

The software that the user uses is the standard OpenRISC kernel and runtime. It has

been stable for some time running on the QEMU simulator that we use for the bulk

of our software development and testing.

To be honest I haven’t run the OpenRISC multicore platform on a physical FGPA

development board for a few years, so just setting up the environment was going

to be a significant undertaking.

For the past few years I have been concentrating on OpenRISC software

so this meant using QEMU which is much more convenient.

To get the environment running we need a bunch of stuff:

- De0 Nano Cyclone IV FPGA dev board with assortment of USB and serial device cables

- fusesoc 2.4.3 - Tool for RTL

package management, building and device programming.

- Quartus Prime Design Software 24.1 - for verilog synthesis and place and route

- The fusesoc OpenRISC multicore SoC - https://github.com/stffrdhrn/de0_nano-multicore

- OpenOCD 0.11.0 for debugging and loading software onto the board

- The OpenRISC toolchain 15.1.0

- Linux kernel source code

- Old kernel patches to get OpenRISC running on the de0 nano

- A busybox rootfs for userspace utilities

There is a lot of information about how to get your FPGA board working with

openrisc in our De0 Nano tutorials.

Please refer to the tutorials if you would like to follow up.

Some notes about what I had to figure out when getting the De0 Nano development environment up again:

- OpenOCD versions after 0.11 no longer work with OpenRISC and it’s

adv_debug_sys debug interface.

Never versions of OpenOCD will connect over the USB Blaster JTAG connection but

requests to write and read fail with CDC failures.

- While debugging the OpenOCD issues I verified our simulated

JTAG connectivity which uses OpenOCD to connect over

jtag_vpi does still work.

- Fusesoc is continuously evolving and the de0_nano and

de0_nano-multicore.

projects needed to be updated to get them working again.

Once the development board was loaded and running a simple hello world program

as per the tutorial I could continue try to run Linux.

Building the Linux Kernel

To build and load the Linux kernel requires the kernel source, a kernel config and a

devicetree

(DTS) file for our De0 Nano multicore board. At the time of this writing we didn’t have one available

in the upstream kernel source tree, so we need to create one. This means we

need to patch and configure the Linux kernel for De0 Nano support.

Patching the Kernel

We can start with the existing OpenRISC multicore kernel config then make some

adjustments. To get started we can configure the kernel with simple_smp_defconfig

as follows.

make ARCH=openrisc CROSS_COMPILE=or1k-linux- simple_smp_defconfig

make

This gives us a good baseline.

We then need to create a device tree that works for the De0 Nano, it is also

almost the same as the simple SMP board but:

- The FPGA SoC runs at 50Mhz instead of 20Mhz

- The FPGA SoC has no ethernet

Starting with the existing simple_smp.dts I modified it creating

de0nano-smp.dts and placed it in

the arch/openrisc/boot/dts directory.

--- arch/openrisc/boot/dts/simple_smp.dts 2026-02-11 20:15:20.244628708 +0000

+++ arch/openrisc/boot/dts/de0nano-smp.dts 2026-02-12 17:24:15.959947375 +0000

@@ -25,12 +25,12 @@

cpu@0 {

compatible = "opencores,or1200-rtlsvn481";

reg = <0>;

- clock-frequency = <20000000>;

+ clock-frequency = <50000000>;

};

cpu@1 {

compatible = "opencores,or1200-rtlsvn481";

reg = <1>;

- clock-frequency = <20000000>;

+ clock-frequency = <50000000>;

};

};

@@ -57,13 +57,6 @@

compatible = "opencores,uart16550-rtlsvn105", "ns16550a";

reg = <0x90000000 0x100>;

interrupts = <2>;

- clock-frequency = <20000000>;

- };

-

- enet0: ethoc@92000000 {

- compatible = "opencores,ethoc";

- reg = <0x92000000 0x800>;

- interrupts = <4>;

- big-endian;

+ clock-frequency = <50000000>;

};

};

Configuring the kernel

The default smp config does not have debugging configured. Run make ARCH=openrisc menuconfig

and enable the following.

Kernel hacking --->

printk and dmesg options --->

[*] Show timing information on printks CONFIG_PRINTK_TIME=y

Compile-time checks and compiler options --->

Debug information (Disable debug information) CONFIG_DEBUG_INFO_DWARF_TOOLCHAIN_DEFAULT=y

[*] Provide GDB scripts for kernel debugging CONFIG_GDB_SCRIPTS=y

General setup --->

[*] Configure standard kernel features (expert users) --->

[*] Load all symbols for debugging/ksymoops CONFIG_KALLSYMS=y

The CONFIG_KALLSYMS seems unremarkable, but it is one of the most important config switches

to enable. This enables our stack traces to show symbol information, which makes it easier to understand

where our crashes happen.

With all of that configured we can build the kernel.

make -j12 \

ARCH=openrisc \

CROSS_COMPILE=or1k-linux- \

CONFIG_INITRAMFS_SOURCE="$HOME/work/openrisc/busybox-rootfs/initramfs $HOME/work/openrisc/busybox-rootfs/initramfs.devnodes" \

CONFIG_BUILTIN_DTB_NAME="de0nano-smp"

When the kernel build is complete we should see our vmlinux image as follows.

$ ls -ltr | tail -n5

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 shorne shorne 104863360 Jan 30 13:30 vmlinux.unstripped

-rw-r--r--. 1 shorne shorne 971587 Jan 30 13:30 System.map

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 shorne shorne 11975 Jan 30 13:30 modules.builtin.modinfo

-rw-r--r--. 1 shorne shorne 1047 Jan 30 13:30 modules.builtin

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 shorne shorne 104763212 Jan 30 13:30 vmlinux

The vmlinux image is an ELF

binary ready to load onto our

board. I have also uploaded a patch for adding the device tree file and a defconfig

to GitHub for easy reproduction.

Booting the Image

Loading the kernel onto our FPGA board using the GDB and OpenOCD commands from the

tutorial the system boots.

The system runs for a while and maybe we can execute commands, 2 CPU’s are

reported online but after some time we get the following lockup and the system

stops.

[ 410.790000] rcu: INFO: rcu_sched self-detected stall on CPU

[ 410.790000] rcu: 0-...!: (2099 ticks this GP) idle=4f64/1/0x40000002 softirq=438/438 fqs=277

[ 410.790000] rcu: (t=2100 jiffies g=-387 q=1845 ncpus=2)

[ 410.790000] rcu: rcu_sched kthread starved for 1544 jiffies! g-387 f0x0 RCU_GP_WAIT_FQS(5) ->state=0x0 ->cpu=1

[ 410.790000] rcu: Unless rcu_sched kthread gets sufficient CPU time, OOM is now expected behavior.

[ 410.790000] rcu: RCU grace-period kthread stack dump:

[ 410.790000] task:rcu_sched state:R running task stack:0 pid:13 tgid:13 ppid:2 task_flags:0x208040 flags:0x00000000

...

[ 411.000000] rcu: Stack dump where RCU GP kthread last ran:

[ 411.000000] Task dump for CPU 1:

[ 411.000000] task:kcompactd0 state:R running task stack:0 pid:29 tgid:29 ppid:2 task_flags:0x218040 flags:0x00000008

[ 411.000000] Call trace:

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] sched_show_task.part.0+0x104/0x138

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] dump_cpu_task+0xd8/0xe0

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] rcu_check_gp_kthread_starvation+0x1bc/0x1e4

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] rcu_sched_clock_irq+0xd00/0xe9c

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] ? ipi_icache_page_inv+0x0/0x24

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] update_process_times+0xa8/0x128

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] tick_nohz_handler+0xd8/0x264

[ 411.050000] [<(ptrval)>] ? tick_program_event+0x78/0x100

[ 411.100000] [<(ptrval)>] tick_nohz_lowres_handler+0x54/0x80

[ 411.100000] [<(ptrval)>] timer_interrupt+0x88/0xc8

[ 411.100000] [<(ptrval)>] _timer_handler+0x84/0x8c

[ 411.100000] [<(ptrval)>] ? smp_call_function_many_cond+0x4d4/0x5b0

[ 411.100000] [<(ptrval)>] ? ipi_icache_page_inv+0x0/0x24

[ 411.100000] [<(ptrval)>] ? smp_call_function_many_cond+0x1bc/0x5b0

[ 411.100000] [<(ptrval)>] ? __alloc_frozen_pages_noprof+0x118/0xde8

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] ? ipi_icache_page_inv+0x14/0x24

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] ? smp_call_function_many_cond+0x4d4/0x5b0

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] on_each_cpu_cond_mask+0x28/0x38

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] smp_icache_page_inv+0x30/0x40

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] update_cache+0x12c/0x160

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] handle_mm_fault+0xc48/0x1cc0

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] ? _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore+0x28/0x38

[ 411.150000] [<(ptrval)>] do_page_fault+0x1d0/0x4b4

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] ? sys_setpgid+0xe4/0x1f8

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] ? _data_page_fault_handler+0x104/0x10c

[ 411.200000] CPU: 0 UID: 0 PID: 61 Comm: sh Not tainted 6.19.0-rc5-simple-smp-00005-g4c0503f58a74 #339 NONE

[ 411.200000] CPU #: 0

[ 411.200000] PC: c00e9dc4 SR: 0000807f SP: c1235da4

[ 411.200000] GPR00: 00000000 GPR01: c1235da4 GPR02: c1235e00 GPR03: 00000006

[ 411.200000] GPR04: c1fe3ae0 GPR05: c1fe3ae0 GPR06: 00000000 GPR07: 00000000

[ 411.200000] GPR08: 00000002 GPR09: c00ea0dc GPR10: c1234000 GPR11: 00000006

[ 411.200000] GPR12: ffffffff GPR13: 00000002 GPR14: 300ef234 GPR15: c09b7b20

[ 411.200000] GPR16: c1fc1b30 GPR17: 00000001 GPR18: c1fe3ae0 GPR19: c1fcffe0

[ 411.200000] GPR20: 00000001 GPR21: ffffffff GPR22: 00000001 GPR23: 00000002

[ 411.200000] GPR24: c0013950 GPR25: 00000000 GPR26: 00000001 GPR27: 00000000

[ 411.200000] GPR28: 01616000 GPR29: 0000000b GPR30: 00000001 GPR31: 00000002

[ 411.200000] RES: 00000006 oGPR11: ffffffff

[ 411.200000] Process sh (pid: 61, stackpage=c12457c0)

[ 411.200000]

[ 411.200000] Stack:

[ 411.200000] Call trace:

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] smp_call_function_many_cond+0x4d4/0x5b0

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] on_each_cpu_cond_mask+0x28/0x38

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] smp_icache_page_inv+0x30/0x40

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] update_cache+0x12c/0x160

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] handle_mm_fault+0xc48/0x1cc0

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] ? _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore+0x28/0x38

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] do_page_fault+0x1d0/0x4b4

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] ? sys_setpgid+0xe4/0x1f8

[ 411.200000] [<(ptrval)>] ? _data_page_fault_handler+0x104/0x10c

[ 411.200000]

[ 411.200000] c1235d84: 0000001c

[ 411.200000] c1235d88: 00000074

[ 411.200000] c1235d8c: c1fc0008

[ 411.200000] c1235d90: 00000000

[ 411.200000] c1235d94: c1235da4

[ 411.200000] c1235d98: c0013964

[ 411.200000] c1235d9c: c1235e00

[ 411.200000] c1235da0: c00ea0dc

[ 411.200000] (c1235da4:) 00000006

From the trace we can see both CPU’s are in similar code locations.

- CPU0 : is in

smp_icache_page_inv -> on_each_cpu_cond_mask -> smp_call_function_many_cond

- CPU1 : is in

smp_icache_page_inv -> on_each_cpu_cond_mask

CPU1 is additionally handling a timer which is reporting the RCU stall, we can

ignore those bits of the stack, as it is reporting the problem for us it is not

the root cause. So what is happening?

Let’s try to understand what is happening. The smp_icache_page_inv function

is called to invalidate an icache page, it will force all CPU’s to invalidate a

cache entry by scheduling each CPU to call a cache invalidation function. This

is scheduled with the smp_call_function_many_cond call.

On CPU0 and CPU1 this is being initiated by a page fault as we see

do_page_fault at the bottom of the stack. The do_page_fault function will be

called when the CPU handles a TLB miss exception or if there was a page fault.

This must mean that a executable page was not available in memory and access to

that page caused a fault, once the page was mapped the icache needs to be

invalidated, this is done via the kernel’s inter-processor interrupt

(IPI) mechanism.

The IPI allows one CPU to request work to be done on other CPUs, this is done

using the on_each_cpu_cond_mask function call.

If we open up the debugger we can see, we are stuck in csd_lock_wait here:

$ or1k-elf-gdb "$HOME/work/linux/vmlinux" -ex 'target remote :3333'

GNU gdb (GDB) 17.0.50.20250614-git

This GDB was configured as "--host=x86_64-pc-linux-gnu --target=or1k-elf".

#0 0xc00ea11c in csd_lock_wait (csd=0xc1fd0000) at kernel/smp.c:351

351 smp_cond_load_acquire(&csd->node.u_flags, !(VAL & CSD_FLAG_LOCK));

Checking the backtrace we see csd_lock_wait is indeed inside the IPI framework

function smp_call_function_many_cond:

(gdb) bt

#0 0xc00ea11c in csd_lock_wait (csd=0xc1fd0000) at kernel/smp.c:351

#1 smp_call_function_many_cond (mask=<optimized out>, func=0xc0013ca8 <ipi_icache_page_inv>, info=0xc1ff8920, scf_flags=<optimized out>,

cond_func=<optimized out>) at kernel/smp.c:877

#2 0x0000002e in ?? ()

Here csd stands for Call Single Data which is part IPI framework’s remote

function call api. The csd_lock_wait function calls smp_cond_load_acquire

which we can see below:

kernel/smp.c

static __always_inline void csd_lock_wait(call_single_data_t *csd)

{

smp_cond_load_acquire(&csd->node.u_flags, !(VAL & CSD_FLAG_LOCK));

}

The CSD_FLAG_LOCK flag is defined as seen here:

include/linux/smp_types.h

enum {

CSD_FLAG_LOCK = 0x01,

...

The smp_cond_load_acquire macro is just a loop waiting for &csd->node.u_flags

the 1 bit CSD_FLAG_LOCK to be cleared.

If we check the value of the u_flags:

(gdb) p/x csd->node.u_flags

$14 = 0x86330004

What is this we see? The value is 0x86330004, but that means the 0x1 bit is not set.

It should be exiting the loop. As the RCU stall warning predicted our CPU is

stuck in tight loop. In this case the loop is in csd_lock_wait.

The value in memory does not match the value the CPU is reading. Is this a

memory synchronization issue? Does the CPU cache incorrectly have the locked

flag?

It’s a Hardware Issue

As this software works fine in QEMU, I was first suspecting this was a hardware

issue. Perhaps there is an issue with cache coherency.

Luckily on OpenRISC we can disable caches. I built the CPU with the caches

disabled, this is done by changing the following module parameters from

ENABLED to NONE as below, then re-synthesizing.

$ grep -r FEATURE.*CACHE ../de0_nano-multicore/

../de0_nano-multicore/rtl/verilog/orpsoc_top.v: .FEATURE_INSTRUCTIONCACHE ("ENABLED"),

../de0_nano-multicore/rtl/verilog/orpsoc_top.v: .FEATURE_DATACACHE ("ENABLED"),

../de0_nano-multicore/rtl/verilog/orpsoc_top.v: .FEATURE_INSTRUCTIONCACHE ("ENABLED"),

../de0_nano-multicore/rtl/verilog/orpsoc_top.v: .FEATURE_DATACACHE ("ENABLED"),

After this the system booted very slow, but we still had hang’s, I was stumped.

Gemini to the Rescue

I thought I would try out Gemini AI to help debug the issue. I was able to paste

in the kernel crash dumps and AI was able to come to the same conclusion

I did. It thought that it may be a memory synchonization issue.

But Gemini was not able to help, it kept chasing red herrings.

- At first it suggsted looking at the memory barriers in the

csd_lock_wait code.

I uploaded some of the OpenRISC kernel source code. It was certain it found the

issue, I was not convinced but humored it. It suggested kernel patches

I applied them and confirmed they didn’t help.

- I asked if it could be a hardware bug, Gemini thought this was a great idea.

If there was an issue with the CPU’s Load Store Unit (LSU) not flushing or

losing writes it could be the cause of the lock not being released. I uploaded

some of the OpenRISC CPU verilog source code. It was certain it found the bug

in the LSU, again I was not concinced looking at it’s patches.

The patches did not improve anything.

We went through several iterations of this, none of the suggestions were correct.

I humored the patches but they did not work.

Gemini does help with discussing the issues, highlighting details, and process

of elimination, but it’s not able think much beyond the evidence I provide.

They seem lack the ability to think beyond it’s current context.

We will need to figure this out on our own.

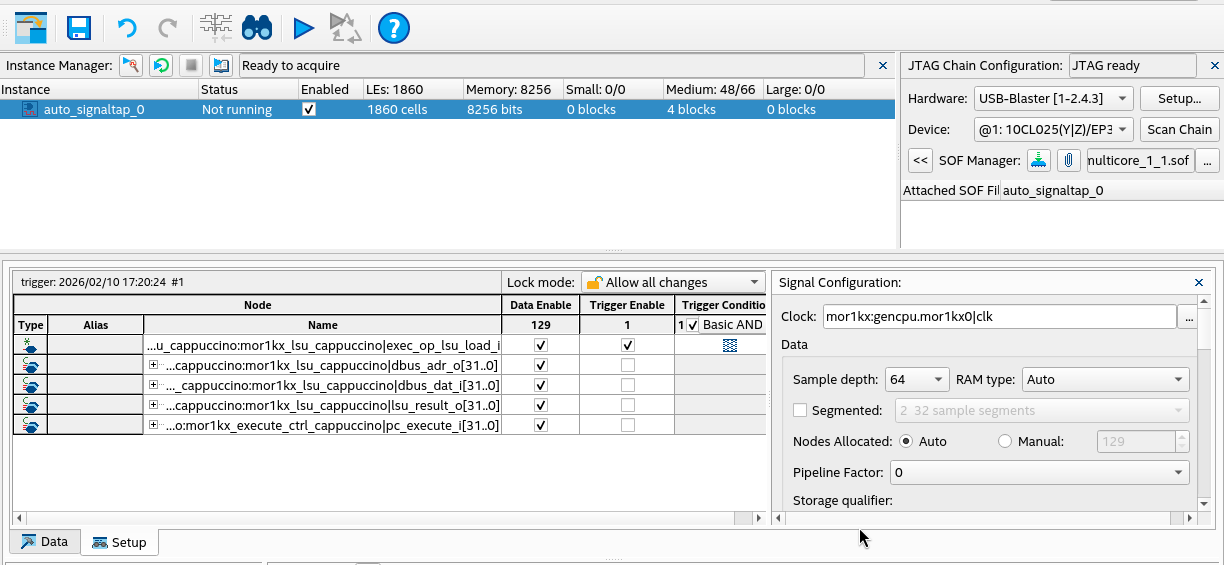

Using a Hardware Debugger

I had some doubt that the values I was seeing in the GDB debug session were

correct. As a last ditch effort I brought up SignalTap, an FPGA virtual logic

analyzer. In other words this is a hardware debugger.

What should we look for in SignalTap? We want to confirm what is really in memory

when the CPU is reading the flags variable from memory in the lock loop.

From our GDB session above we recall the csd_lock_wait lock loop was around PC address 0xc00ea11c.

If we dump this area of the Linux binary we see the following:

$ or1k-elf-objdump -d vmlinux | grep -C5 c00ea11c

c00ea108: 0c 00 00 07 l.bnf c00ea124 <smp_call_function_many_cond+0x1c4>

c00ea10c: 15 00 00 00 l.nop 0x0

c00ea110: 86 33 00 04 l.lwz r17,4(r19) <---------------------------------+

c00ea114: a6 31 00 01 l.andi r17,r17,0x1 |

c00ea118: bc 11 00 00 l.sfeqi r17,0 |

c00ea11c:<-- 0f ff ff fd l.bnf c00ea110 <smp_call_function_many_cond+0x1b0> -+

c00ea120: 15 00 00 00 l.nop 0x0

c00ea124: 22 00 00 00 l.msync

c00ea128: bc 17 00 02 l.sfeqi r23,2

c00ea12c: 0f ff ff e1 l.bnf c00ea0b0 <smp_call_function_many_cond+0x150>

c00ea130: aa 20 00 01 l.ori r17,r0,0x1

We can see the l.lwz instruction is used to read in the flags value from

memory. The l.lwz instruction instructs the CPU to load data at an address in

memory to a CPU register. The CPU module that handles memory access is called

the Load Store Unit (LSU). Let’s setup the logic analyzer to capture the LSU

signals.

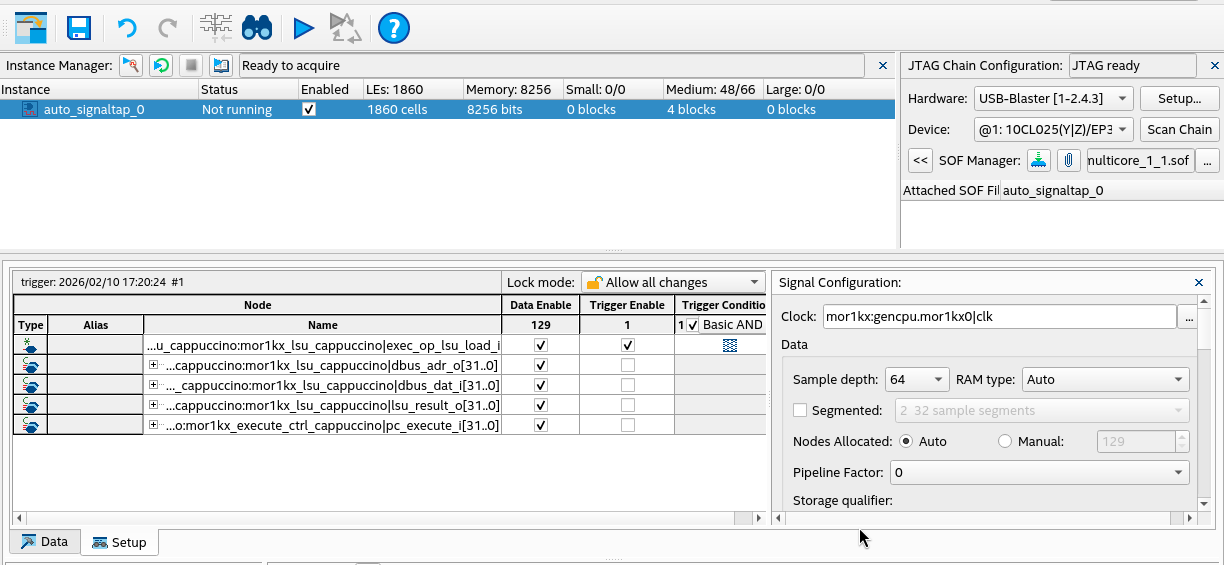

In CPU core 0’s module mor1kx_lsu_cappuccino select signals:

pc_execute_i - The PC for the execute stage, this lets us know which instruction is waiting to executeexec_op_lsu_load_i - Signal that is asserted when the LSU is being asked to perform a loaddbus_adr_o - The address being communicated from the LSU to the memory bus for the data loaddbus_dat_i - The data being communicated from the memory bus back to the LSUlsu_result_o - The data captured by the LSU to be written to the register file

Note 1 During this build, we disable the data cache to make sure loads are not

cached. Otherwise our load would go out to the memory bus one time and be hard

to capture in the logic analyzer.

Note 2 We select only signals on CPU 0, as the csd_lock_wait lock loop is occurring on both CPUs.

Note 3 I found that if I added too many signals to SignalTap that Linux would fail to boot

as the CPU would get stuck with BUS errors. So be aware.

In SignalTap our setup looks like the following:

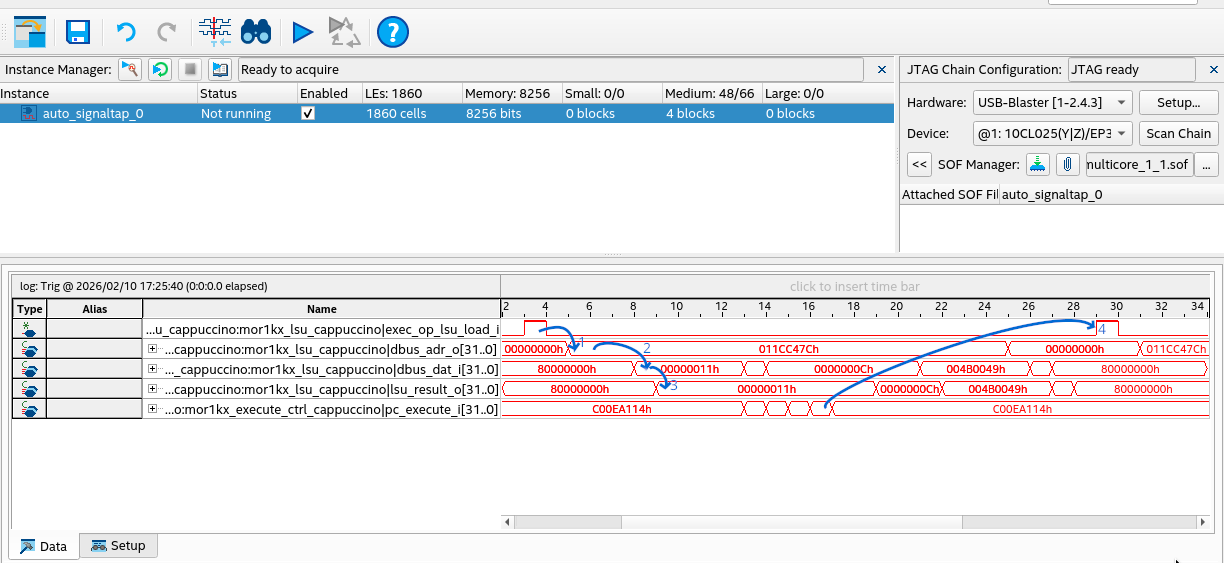

After the setup we can try to boot the kernel and observe the lockup. When the lockup occurs

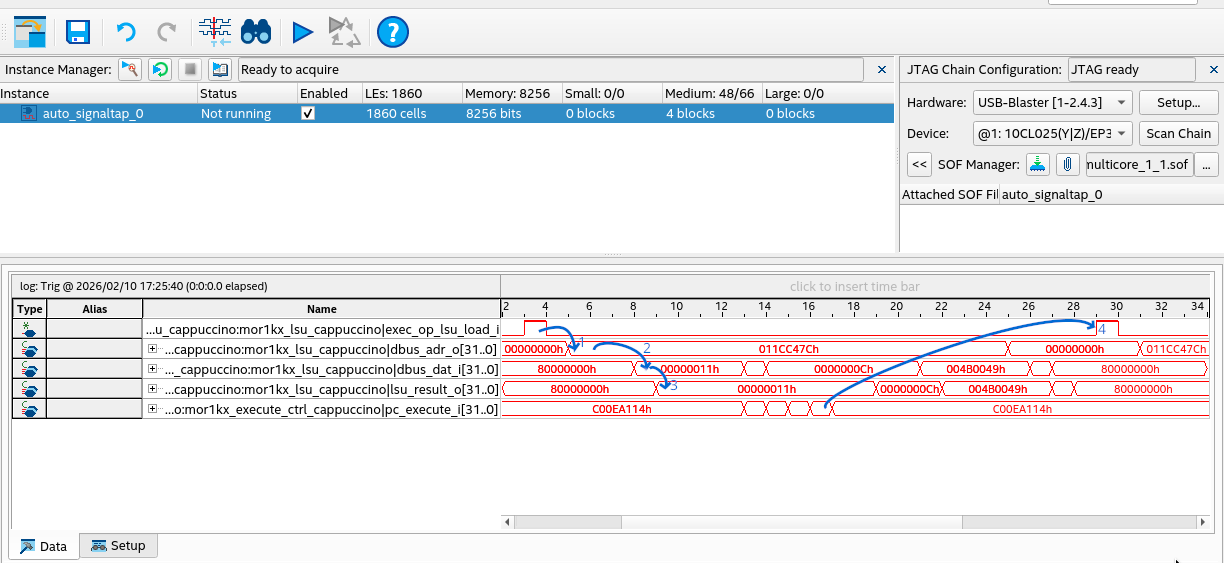

if we capture data we see the below:

I have annotated the transitions in the trace:

- Moments after the

exec_op_lsu_load_i signal is asserted, the dbus_adr_o is set to

0x011cc47c. This is the memory address to be read.

- Next we see

0x11 on dbus_dat_i. This is the value read from memory.

- After this the value

0x11 is outputted on lsu_result_o confirming this is the value read.

- Finally after a few instructions the loop continues again and

exec_op_lsu_load_i is asserted.

Here we have confirmed the CPU is properly reading 0x11, the lock is still held. What does this mean

does it mean that CPU 1 (the secondary CPU) did not handle the IPI and release the lock?

It does mean that our GDB analysis is wrong. There is no memory synchonization issue

and the hardware is behaving as expect. We need another idea.

Actually, it’s a Kernel Issue

Since we know that is seems some IPIs are not getting handled properly

it would be good to be able to know how many IPIs are getting sent and lost.

I added a patch to capture and dump IPI stats

when OpenRISC crashes. What we see below is that CPU 1 is receiving no IPIs while

CPU 0 has received all IPIs sent by CPU 1.

[ 648.180000] CPU: 0 UID: 0 PID: 1 Comm: init Tainted: G L 6.19.0-rc4-de0nano-smp-00002-ga7fc4d

[ 648.180000] Tainted: [L]=SOFTLOCKUP

[ 648.180000] CPU #: 0

[ 648.180000] PC: c00ea100 SR: 0000807f SP: c1031cf8

[ 648.180000] GPR00: 00000000 GPR01: c1031cf8 GPR02: c1031d54 GPR03: 00000006

[ 648.180000] GPR04: c1fe4ae0 GPR05: c1fe4ae0 GPR06: 00000000 GPR07: 00000000

[ 648.180000] GPR08: 00000002 GPR09: c00ea420 GPR10: c1030000 GPR11: 00000006

[ 648.180000] GPR12: 00000029 GPR13: 00000002 GPR14: c1fe4ae0 GPR15: 0000000b

[ 648.180000] GPR16: c1fc1b60 GPR17: 00000011 GPR18: c1fe4ae0 GPR19: c1fd0010

[ 648.180000] GPR20: 00000001 GPR21: ffffffff GPR22: 00000001 GPR23: 00000002

[ 648.180000] GPR24: c0013c98 GPR25: 00000000 GPR26: 00000001 GPR27: c09cd7b0

[ 648.180000] GPR28: 01608000 GPR29: c09c4524 GPR30: 00000006 GPR31: 00000000

[ 648.180000] RES: 00000006 oGPR11: ffffffff

...

[ 648.180000] IPI stats:

[ 648.180000] Wakeup IPIs sent: 1 recv: 0

[ 648.180000] Rescheduling IPIs sent: 8 recv: 0

[ 648.180000] Function call IPIs sent: 0 recv: 0

[ 648.180000] Function single call IPIs sent: 41 recv: 46

...

[ 660.260000] CPU: 1 UID: 0 PID: 29 Comm: kcompactd0 Tainted: G L 6.19.0-rc4-de0nano-smp-00002-

[ 660.260000] Tainted: [L]=SOFTLOCKUP

[ 660.260000] CPU #: 1

[ 660.260000] PC: c053ca40 SR: 0000827f SP: c1095b58

[ 660.260000] GPR00: 00000000 GPR01: c1095b58 GPR02: c1095b60 GPR03: c11f003c

[ 660.260000] GPR04: c11f20c0 GPR05: 3002e000 GPR06: c1095b64 GPR07: c1095b60

[ 660.260000] GPR08: 00000000 GPR09: c0145c00 GPR10: c1094000 GPR11: c11fc05c

[ 660.260000] GPR12: 00000000 GPR13: 0002003d GPR14: c1095d2c GPR15: 00000000

[ 660.260000] GPR16: c1095b98 GPR17: 0000001d GPR18: c11f0000 GPR19: 0000001e

[ 660.260000] GPR20: 30030000 GPR21: 001f001d GPR22: c1fe401c GPR23: c09cd7b0

[ 660.260000] GPR24: ff000000 GPR25: 00000001 GPR26: 01000000 GPR27: c1ff21a4

[ 660.260000] GPR28: 00000000 GPR29: c1095dd8 GPR30: 3002e000 GPR31: 00000002

[ 660.260000] RES: c11fc05c oGPR11: ffffffff

...

[ 660.300000] IPI stats:

[ 660.300000] Wakeup IPIs sent: 0 recv: 0

[ 660.310000] Rescheduling IPIs sent: 0 recv: 0

[ 660.310000] Function call IPIs sent: 0 recv: 0

[ 660.310000] Function single call IPIs sent: 46 recv: 0

Why is this? With some extra debugging I found that the programmable interrupt

controller mask register (PICMR) was 0x0 on CPU 1. This means that all interrupts

on CPU 1 are masked and CPU 1 will never receive any interrupts.

After a quick patch to unmask IPIs

on secondary CPUs the system stability was fixed. This is the simple patch:

diff --git a/arch/openrisc/kernel/smp.c b/arch/openrisc/kernel/smp.c

index 86da4bc5ee0b..db3f6ff0b54a 100644

--- a/arch/openrisc/kernel/smp.c

+++ b/arch/openrisc/kernel/smp.c

@@ -138,6 +138,9 @@ asmlinkage __init void secondary_start_kernel(void)

synchronise_count_slave(cpu);

set_cpu_online(cpu, true);

+ // Enable IPIs, hack

+ mtspr(SPR_PICMR, mfspr(SPR_PICMR) | 0x2);

+

local_irq_enable();

/*

* OK, it's off to the idle thread for us

Fixing the Bug Upstream

Simply unmasking the interrupts in Linux as I did above in the hack would not be accepted upstream.

There are irqchip APIs that handle interrupt unmasking.

The OpenRISC IPI patch

for the Linux 6.20/7.0 release updates the IPI interrupt driver to

register a percpu_irq which allows us to unmask the irq handler on each CPU.

In the patch series

I also added De0 Nano single core and multicore board

configurations to allow for easier board bring up.

What went wrong with GDB?

Why did GDB return the incorrect values when we were debugging initially?

GDB is not broken, but it could be improved when debugging kernel code.

Let’s look again at the GDB session and look at the addresses of our variables.

(gdb) l

346 {

347 }

348

349 static __always_inline void csd_lock_wait(call_single_data_t *csd)

350 {

351 smp_cond_load_acquire(&csd->node.u_flags, !(VAL & CSD_FLAG_LOCK));

352 }

353 #endif

(gdb) p/x csd->node.u_flags

$14 = 0x86330004

(gdb) p/x &csd->node.u_flags

$15 = 0xc1fd0004

Here we see the value GDB reads is 0x86330004, but the address of the variable is

0xc1fd0004. This is a kernel address as we see the 0xc0000000 address offset.

Let’s inspect the assembly code that is running.

(gdb) p/x $npc

$11 = 0xc00ea11c

(gdb) x/12i $npc-0xc000000c

0xea110: l.lwz r17,4(r19)

0xea114: l.andi r17,r17,0x1

0xea118: l.sfeqi r17,0

-->0xea11c: l.bnf 0xea110

0xea120: l.nop 0x0

0xea124: l.msync

0xea128: l.sfeqi r23,2

0xea12c: l.bnf 0xea0b0

0xea130: l.ori r17,r0,0x1

0xea134: l.lwz r16,56(r1)

0xea138: l.lwz r18,60(r1)

0xea13c: l.lwz r20,64(r1)

Here we see the familiar loop, the register r19 stores the address of

csd->node and u_flags is at a 4 byte offset, hence l.lwz r17,4(r19).

The register r17 stores the value read from memory, then masked with 0x1.

We can see this below.

(gdb) p/x $r17

$4 = 0x1

(gdb) p/x $r19

$5 = 0xc1fd0000

(gdb) x/12x $r19

0xc1fd0000: 0x862a0008 0x862a0008 0x862a0008 0x862a0008

0xc1fd0010: 0x862a0008 0x862a0008 0x862a0008 0x862a0008

0xc1fd0020: 0x862a0008 0x862a0008 0x862a0008 0x862a0008

Here we see r19 is 0xc1fd0000 and if we inspect the memory at this location

we see values like 0x862a0008, which is strange.

Above we discussed these are kernel addresses, offset by 0xc0000000.

When the kernel does memory reads these will be mapped by the MMU to a physical address, in this case

0x01fd0004.

We can apply the offset ourselves and inspect memory as follows.

(gdb) x/12x $r19-0xc0000000

0x1fd0000: 0x00000000 0x00000011 0xc0013ca8 0xc1ff8920

0x1fd0010: 0x0000fe00 0x00000000 0x00000400 0x00000000

0x1fd0020: 0x01fd01fd 0x00000005 0x0000002e 0x0000002e

Bingo, this shows that we have 0x11 at 0x1fd0004 the lock value. Memory does

indeed contain 0x11 the same as the value read by the CPU.

When GDB does memory reads the debug interface issues reads directly to the

memory bus. The CPU and MMU are not involved. This means, at the moment, we

need to be careful when inspecting memory and be sure to perform the offsets

ourselves.

Conclusion

Debugging accross the hardware-software boundary requires a bit of experience

and a whole lot of parience. We initially thought that this was a harware

issue, but then eventually found a trivial issue in the OpenRISC multicore support

drivers. It took time and a few different tools to convince ourselves that the

hardware was fine. After refocusing on the kernel and building some tools

(the IPI stats report) we found the clue we needed.

This highlights the importance in embedded systems to know your tools and

architecturte. Or, in our case, remember that the MMU does not translate memory

reads over the JTAG interface. With the bug fixed and De0 Nano support merged upstream

Linux on the OpenRISC platform not now more accessible and stable than before.

Followups

Working on this issue highlighted that there are a few things to improve

in OpenRISC including:

- Tutorials and Upstreaming patches

- OpenOCD is currently broken for OpenRISC

- OpenOCD doesn’t support multicore (multicore patches never upstreamed)

- OpenOCD / GDB bugs

24 Aug 2023

In this series we introduce the OpenRISC

glibc FPU

port and the effort required to get user space FPU support into OpenRISC Linux.

Adding FPU support to user space

applications is a full stack project covering:

Have a look at previous articles if you need to catch up. In this article we will cover

updates done to the Linux kernel, GCC (done long ago) and GDB for debugging.

Porting Linux to an FPU

Supporting hardware floating point operations in Linux user space applications

means adding the ability for the Linux kernel to store and restore FPU state

upon context switches. This allows multiple programs to use the FPU at the same

time as if each program has it’s own floating point hardware. The kernel allows

programs to multiplex usage of the FPU transparently. This is similar to how

the kernel allows user programs to share other hardware like the CPU and

Memory.

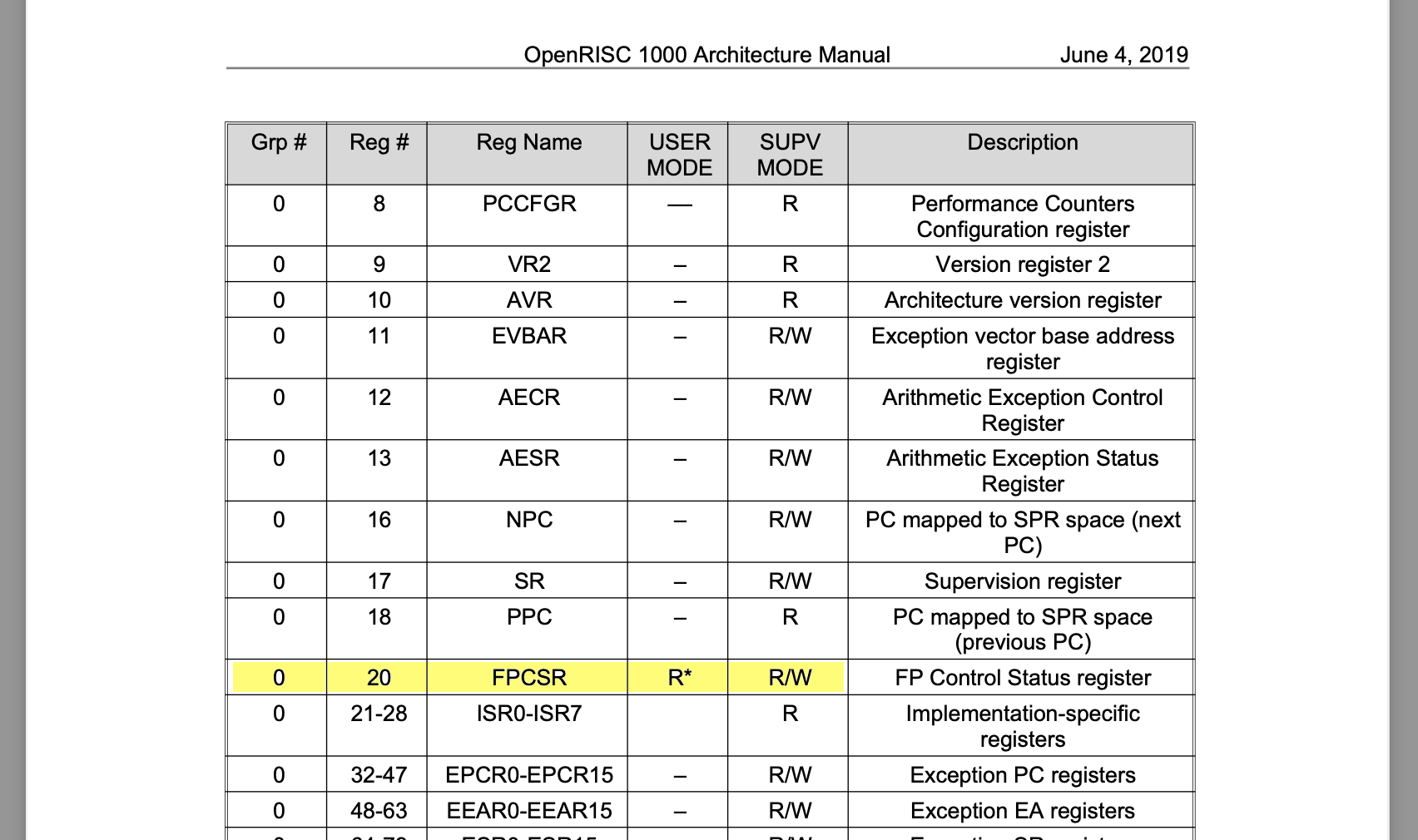

On OpenRISC this requires to only add one addition register, the floating point

control and status register (FPCSR) to to context switches. The FPCSR

contains status bits pertaining to rounding mode and exceptions.

We will cover three places where Linux needs to store FPU state:

- Context Switching

- Exception Context (Signal Frames)

- Register Sets

Context Switching

In order for the kernel to be able to support FPU usage in user space programs

it needs to be able to save and restore the FPU state during context switches.

Let’s look at the different kinds of context switches that happen in the Linux

Kernel to understand where FPU state needs to be stored and restored.

For our discussion purposes we will define a context switch as being

when one CPU state (context) is saved from CPU hardware (registers and program

counter) to memory and then another CPU state is loaded form memory to CPU

hardware. This can happen in a few ways.

- When handling exceptions such as interrupts

- When the scheduler wants to swap out one process for another.

Furthermore, exceptions may be categorized into one of two cases: Interrupts and

System calls. For each of these a different amount of CPU state needs to be saved.

- Interrupts - for timers, hardware interrupts, illegal instructions etc,

for this case the full context will be saved. As the switch is not

anticipated by the currently running program.

- System calls - for system calls the user space program knows that it is making a function

call and therefore will save required state as per OpenRISC calling conventions.

In this case the kernel needs to save only callee saved registers.

Below are outlines of the sequence of operations that take place when

transitioning from Interrupts and System calls into kernel code. It highlights

at what point state is saved with the INT,

kINT and FPU labels.

The monospace labels below correspond to the actual assembly labels in entry.S,

the part of the OpenRISC Linux kernel that handles entry into kernel code.

Interrupts (slow path)

EXCEPTION_ENTRY - all INT state is saved- Handle exception in kernel code

_resume_userspace - Check thread_info for work pending- If work pending

_work_pending - Call do_work_pending

- Check if reschedule needed

- If so, performs

_switch which save/restores kINT

and FPU state

- Check for pending signals

- If so, performs

do_signal which save/restores FPU state

RESTORE_ALL - all INT state is restored and return to user space

System calls (fast path)

_sys_call_handler - callee saved registers are saved- Handle syscall in kernel code

_syscall_check_work - Check thread_info for work pending- If work pending

- Save additional INT state

_work_pending - Call do_work_pending

- Check if reschedule needed

- If so, performs

_switch which save/restores kINT

and FPU state

- Check for pending signals

- If so, performs

do_signal which save/restores FPU state

RESTORE_ALL - all INT state is restored and return to user space

_syscall_resume_userspace - restore callee saved registers return to user space.

Some key points to note on the above:

- INT denotes the interrupts program’s register state.

- kINT denotes the kernel’s register state before/after a context switch.

- FPU deones FPU state

- In both cases step 4 checks for work pending, which may cause task

rescheduling in which case a Context Switch (or task switch) will

be performed.

If rescheduling is not performed then after the sequence is complete processing

will resume where it left off.

- Step 1, when switching from user mode to kernel mode is called a Mode Switch

- Interrupts may happen in user mode or kernel mode

- System calls will only happen in user mode

- FPU state only needs to be saved and restored for user mode programs,

because kernel mode programs, in general, do not use the FPU.

- The current version of the OpenRISC port as of

v6.8 save and restores both

INT and FPU state

what is shown before is a more optimized mechanism of only saving FPU state when needed. Further optimizations could

be still make to only save FPU state for user space, and not save/restore if it is already done.

With these principal’s in mind we can now look at how the mechanics of context

switching works.

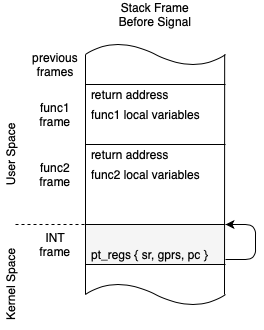

Upon a Mode Switch from user mode to kernel mode the process thread

stack switches from using a user space stack to the associated kernel space

stack. The required state is stored to a stack frame in a pt_regs structure.

The pt_regs structure (originally ptrace registers) represents the CPU

registers and program counter context that needs to be saved.

Below we can see how the kernel stack and user space stack relate.

kernel space

+--------------+ +--------------+

| Kernel Stack | | Kernel stack |

| | | | | |

| v | | | |

| pt_regs' -------\ | v |

| v | | | pt_regs' --------\

| pt_reg'' |<+ | | v |<+ |

| | | | | | | |

+--------------+ | | +--------------+ | |

| thread_info | | | | thread_info | | |

| *task | | | | *task | | |

| ksp ----------/ | | ksp-----------/ |

+--------------+ | +--------------+ |

| |

0xc0000000 | |

---------------------|----------------------|-----

| |

process a | process b |

+--------------+ | +------------+ |

| User Stack | | | User Stack | |

| | | | | | | |

| V |<---+ | v |<-----+

| | | |

| | | |

| text | | text |

| heap | | heap |

+--------------+ +------------+

0x00000000

user space

process a

In the above diagram notice how there are 2 set’s of pt_regs for process a.

The pt_regs’ structure represents the user space registers (INT)

that are saved during the switch from user mode to kernel mode. Notice how

the pt_regs’ structure has an arrow pointing the user space stack, that’s the

saved stack pointer. The second pt_regs’’ structure represents the frozen

kernel state (kINT)

that was saved before a task switch was performed.

process b

Also in the diagram above we can see process b has only a pt_regs’ (INT)

structure saved on the stack and does not currently have a pt_regs’’ (kINT)

structure saved. This indicates that that this process is currently running in

kernel space and is not yet frozen.

As we can see here, for OpenRISC there are two places to store state.

- The mode switch context is saved to a

pt_regs structure on the kernel

stack represented by pt_regs’ at this point only integer registers need to

be saved. This is represents the user process state.

- The context switch context is stored by OpenRISC again on the stack,

represented by pt_regs’‘. This represents the kernel’s state before a

task switch. All state that the kernel needs to resume later is stored. In

other architectures this state is not stored on the stack but to the

task

structure or to the thread_info structure. This context may store the all

extra registers including FPU and Vector registers.

Note In the above diagram we can see the kernel stack and

thread_info live in

the same memory space. This is a source of security issues and many

architectures have moved to support

virtually mapped kernel stacks,

OpenRISC does not yet support this and it would be a good opportunity

for improvement.

The structure of the pt_regs used by OpenRISC is as per below:

struct pt_regs {

long gpr[32];

long pc;

/* For restarting system calls:

* Set to syscall number for syscall exceptions,

* -1 for all other exceptions.

*/

long orig_gpr11; /* For restarting system calls */

long dummy; /* Cheap alignment fix */

long dummy2; /* Cheap alignment fix */

};

The structure of thread_struct now used by OpenRISC to store the

user specific FPU state is as per below:

struct thread_struct {

long fpcsr; /* Floating point control status register. */

};

The patches to OpenRISC added to support saving and restoring FPU state

during context switches are below:

- 2023-04-26 63d7f9f11e5e Stafford Horne openrisc: Support storing and restoring fpu state

- 2024-03-14 ead6248f25e1 Stafford Horne openrisc: Move FPU state out of pt_regs

Signals and Signal Frames.

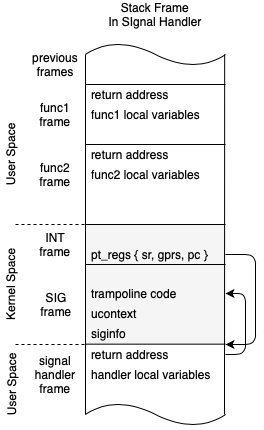

Signal frames are another place that we want FPU’s state, namely FPCSR, to be available.

When a user process receives a signal it executes a signal handler in the

process space on a stack slightly outside it’s current stack. This is setup

with setup_rt_frame.

As we saw above signals are received after syscalls or exceptions, during the

do_pending_work phase of the entry code. This means means FPU state will need

to be saved and restored.

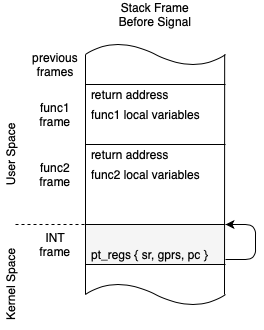

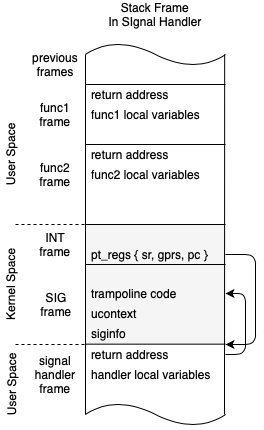

Again, we can look at the stack frames to paint a picture of how this works.

kernel space

+--------------+

| Kernel Stack |

| | |

| v |

| pt_regs' --------------------------\

| |<+ |

| | | |

| | | |

+--------------+ | |

| thread_info | | |

| *task | | |

| ksp ----------/ |

+--------------+ |

|

0xc0000000 |

------------------- |

|

process a |

+--------------+ |

| User Stack | |

| | | |

| V | |

|xxxxxxxxxxxxxx|> STACK_FRAME_OVERHEAD |

| siginfo |\ |

| ucontext | >- sigframe |

| retcode[] |/ |

| |<-----------------------/

| |

| text |

| heap |

+--------------+

0x00000000

user space

Here we can see that when we enter a signal handler, we can get a bunch of stuff

stuffed in the stack in a sigframe structure. This includes the ucontext,

or user context which points to the original state of the program, registers and

all. It also includes a bit of code, retcode, which is a trampoline to bring us

back into the kernel after the signal handler finishes.

Note we could also setup an alternate

signalstack

to use instead of stuffing stuff onto the main user stack. The

above example is the default behaviour.

The user pt_regs (as we called pt_regs’) is updated before returning to user

space to execute the signal handler code by updating the registers as follows:

sp: stack pinter updated to point to a new user stack area below sigframe

pc: program counter: sa_handler(

r3: argument 1: signo,

r4: argument 2: &siginfo

r5: argument 3: &ucontext)

r9: link register: retcode[]

Now, when we return from the kernel to user space, user space will resume in the

signal handler, which runs within the user process context.

After the signal handler completes it will execute the retcode

block which is setup to call the special system call rt_sigreturn.

Note for OpenRISC this means the stack has to be executable. Which is

a

major security vulnerability.

Modern architectures do not have executable stacks and use

vdso

or is provided by libc in

sa_restorer.

The rt_sigreturn system call will restore the ucontext registers (which

may have been updated by the signal handler) to the user pt_regs on the

kernel stack. This allows us to either restore the user context before the

signal was received or return to a new context setup by the signal handler.

A note on user space ABI compatibility for signals.

We need to to provide and restore the FPU FPCSR during signals via

ucontext but also not break user space ABI. The ABI is important because

kernel and user space programs may be built at different times. This means the

layout of existing fields in ucontext cannot change. As we can see below by

comparing the ucontext definitions from Linux, glibc and musl each program

maintains their own separate header file.

In Linux we cannot add fields to uc_sigcontext as it would make uc_sigmask

unable to be read. Fortunately we had a bit of space in sigcontext in the

unused oldmask field which we could repurpose for FPCSR.

The structure used by Linux to populate the signal frame is:

From: uapi/asm-generic/ucontext.h

struct ucontext {

unsigned long uc_flags;

struct ucontext *uc_link;

stack_t uc_stack;

struct sigcontext uc_mcontext;

sigset_t uc_sigmask;

};

From: uapi/asm/ptrace.h

struct sigcontext {

struct user_regs_struct regs; /* needs to be first */

union {

unsigned long fpcsr;

unsigned long oldmask; /* unused */

};

};

Note In

sigcontext originally a

union was not used

and

caused ABI breakage; which was soon fixed.

From: uapi/asm/sigcontext.h

struct user_regs_struct {

unsigned long gpr[32];

unsigned long pc;

unsigned long sr;

};

The structure that glibc expects is.

/* Context to describe whole processor state. */

typedef struct

{

unsigned long int __gprs[__NGREG];

unsigned long int __pc;

unsigned long int __sr;

} mcontext_t;

/* Userlevel context. */

typedef struct ucontext_t

{

unsigned long int __uc_flags;

struct ucontext_t *uc_link;

stack_t uc_stack;

mcontext_t uc_mcontext;

sigset_t uc_sigmask;

} ucontext_t;

Note This is broken, the struct mcontext_t in glibc is

missing the space for oldmask.

The structure used by musl is:

typedef struct sigcontext {

struct {

unsigned long gpr[32];

unsigned long pc;

unsigned long sr;

} regs;

unsigned long oldmask;

} mcontext_t;

typedef struct __ucontext {

unsigned long uc_flags;

struct __ucontext *uc_link;

stack_t uc_stack;

mcontext_t uc_mcontext;

sigset_t uc_sigmask;

} ucontext_t;

Below were the patches the to OpenRISC kernel to add floating point state to the

signal API. This originally caused some ABI breakage and was fixed in the second patch.

- 2023-04-26 27267655c531 Stafford Horne openrisc: Support floating point user api

- 2023-07-10 dceaafd66881 Stafford Horne openrisc: Union fpcsr and oldmask in sigcontext to unbreak userspace ABI

Register sets

Register sets provide debuggers the ability to read and save the state of

registers in other processes. This is done via the ptrace

PTRACE_GETREGSET and PTRACE_SETREGSET requests.

Regsets also define what is dumped to core dumps when a process crashes.

In OpenRISC we added the ability to get and set the FPCSR register

with the following patches:

- 2023-04-26 c91b4a07655d Stafford Horne openrisc: Add floating point regset (shorne/or1k-6.4-updates, or1k-6.4-updates)

- 2024-03-14 14f89b18c117 Stafford Horne openrisc: Move FPU state out of pt_regs

Porting GCC to an FPU

Supporting FPU Instructions

I ported GCC to the OpenRISC FPU back in 2019

, this entailed defining new instructions in the RTL machine description for

example:

(define_insn "plussf3"

[(set (match_operand:SF 0 "register_operand" "=r")

(plus:SF (match_operand:SF 1 "register_operand" "r")

(match_operand:SF 2 "register_operand" "r")))]

"TARGET_HARD_FLOAT"

"lf.add.s\t%d0, %d1, %d2"

[(set_attr "type" "fpu")])

(define_insn "minussf3"

[(set (match_operand:SF 0 "register_operand" "=r")

(minus:SF (match_operand:SF 1 "register_operand" "r")

(match_operand:SF 2 "register_operand" "r")))]

"TARGET_HARD_FLOAT"

"lf.sub.s\t%d0, %d1, %d2"

[(set_attr "type" "fpu")])

The above is a simplified example of GCC Register Transfer Language(RTL)

lisp expressions. Note, the real expression actually uses mode iterators and is a bit harder to understand, hence the simplified version above.

These expressions are used for translating the GCC compiler RTL from it’s abstract syntax tree

form to actual machine instructions.

Notice how the above expressions are in the format (define_insn INSN_NAME RTL_PATTERN CONDITION MACHINE_INSN ...). If

we break it down we see:

INSN_NAME - this is a unique name given to the instruction.RTL_PATTERN - this is a pattern we look for in the RTL tree, Notice how the lisp represents 3 registers connected by the instruction node.CONDITION - this is used to enable the instruction, in our case we use TARGET_HARD_FLOAT. This means if the GCC hardware floating point

option is enabled this expression will be enabled.MACHINE_INSN - this represents the actual OpenRISC assembly instruction that will be output.

Supporting Glibc Math

In order for glibc to properly support floating point operations GCC needs to do

a bit more than just support outputting floating point instructions. Another

component of GCC is software floating point emulation. When there are

operations not supported by hardware GCC needs to fallback to using software

emulation. With way GCC and GLIBC weave software math routines and floating

point instructions we can think of the FPU as a math accelerator. For example,

the floating point square root operation is not provided by OpenRISC hardware.

When operations like square root are not available by hardware glibc will inject

software routines to handle the operation. The outputted square root routine

may use hardware multiply lf.mul.s and divide lf.div.s operations to

accelerate the emulation.

In order for this to work correctly the rounding mode and exception state of the

FPU and libgcc emulation need to by in sync. Notably, we had one patch to fix an

issue with exceptions not being in sync which was found when running glibc

tests.

- 2023-03-19 33fb1625992 or1k: Do not clear existing FPU exceptions before updating

The libc math routines include:

- Trigonometry functions - For example

float sinf (float x)

- Logarithm functions - For example

float logf (float x)

- Hyperbolic functions - For example

float ccoshf (complex float z)

The above just names a few, but as you can imagine the floating point acceleration

provided by the FPU is essential for performant scientific applications.

Adding debugging capabilities for an FPU

FPU debugging allows a user to inspect the FPU specific registers.

This includes FPU state registers and flags as well as view the floating point

values in each general purpose register. This is not yet implemented on

OpenRISC.

This will be something others can take up. The work required is to map

Linux FPU register sets to GDB.

Summary

In summary adding floating point support to Linux revolved around adding one more register, the FPCSR,

to context switches and a few other places.

GCC fixes were needed to make sure hardware and software floating point routines could work together.

There are still improvements that can be done for the Linux port as noted above. In the next

article we will wrap things up by showing the glibc port.

Further Reading

22 Aug 2023

In the last article we introduced the

OpenRISC glibc FPU port and the effort required to get user space FPU support

into OpenRISC linux user applications. We explained how the FPU port is a

fullstack project covering:

- Architecture Specification

- Simulators and CPU implementations

- Linux Kernel support

- GCC Instructions and Soft FPU

- Binutils/GDB Debugging Support

- glibc support

In this entry we will cover updating Simulators and CPU implementations to support

the architecture changes which are called for as per the previous article.

- Allowing usermode programs to update the FPCSR register

- Detecting tininess before rounding

Simulator Updates

The simulators used for testing OpenRISC software without hardware are QEMU

and or1ksim. They both needed to be updated to cohere to the specification

updates discussed above.

Or1ksim Updates

The OpenRISC architectue simulator or1ksim has been updated with the single patch:

cpu: Allow FPCSR to be read/written in user mode.

The softfloat FPU implementation was already configured to detect tininess before

rounding.

If you are interested you can download and run the simulator and test this out

with a docker image pulled from docker hub using the following:

# using podman instead of docker, you can use docker here too

podman pull stffrdhrn/or1k-sim-env:latest

podman run -it --rm stffrdhrn/or1k-sim-env:latest

root@9a4a52eec8ee:/tmp# or1k-elf-sim -version

Seeding random generator with value 0x4a3c2bbd

OpenRISC 1000 Architectural Simulator, version 2023-08-20

This starts up an environment which has access to the OpenRISC architecture

simulator and a GNU compiler toolchain. While still in the container can run a

quick test using the FPU as follows:

# Create a test program using OpenRISC FPU

cat > fpee.c <<EOF

#include <float.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <or1k-sprs.h>

#include <or1k-support.h>

static void enter_user_mode() {

int32_t sr = or1k_mfspr(OR1K_SPR_SYS_SR_ADDR);

sr &= ~OR1K_SPR_SYS_SR_SM_MASK;

or1k_mtspr(OR1K_SPR_SYS_SR_ADDR, sr);

}

static void enable_fpu_exceptions() {

unsigned long fpcsr = OR1K_SPR_SYS_FPCSR_FPEE_MASK;

or1k_mtspr(OR1K_SPR_SYS_FPCSR_ADDR, fpcsr);

}

static void fpe_handler() {

printf("Got FPU Exception, PC: 0x%lx\n", or1k_mfspr(OR1K_SPR_SYS_EPCR_BASE));

}

int main() {

float result;

or1k_exception_handler_add(0xd, fpe_handler);

#ifdef USER_MODE

/* Note, printf here also allocates some memory allowing user mode runtime to

work. */

printf("Enabling user mode\n");

enter_user_mode();

#endif

enable_fpu_exceptions();

printf("Exceptions enabled, now DIV 3.14 / 0!\n");

result = 3.14f / 0.0f;

/* Verify we see infinity. */

printf("Result: %f\n", result);

/* Verify we see DZF set. */

printf("FPCSR: %x\n", or1k_mfspr(OR1K_SPR_SYS_FPCSR_ADDR));

#ifdef USER_MODE

asm volatile("l.movhi r3, 0; l.nop 1"); /* Exit sim, now */

#endif

return 0;

}

EOF

# Compile the program

or1k-elf-gcc -g -O2 -mhard-float fpee.c -o fpee

or1k-elf-sim -f /opt/or1k/sim.cfg ./fpee

# Expected results

# Program Header: PT_LOAD, vaddr: 0x00000000, paddr: 0x0 offset: 0x00002000, filesz: 0x000065ab, memsz: 0x000065ab

# Program Header: PT_LOAD, vaddr: 0x000085ac, paddr: 0x85ac offset: 0x000085ac, filesz: 0x000000c8, memsz: 0x0000046c

# WARNING: sim_init: Debug module not enabled, cannot start remote service to GDB

# Exceptions enabled, now DIV 3.14 / 0!

# Got FPU Exception, PC: 0x2068

# Result: f

# FPCSR: 801

# Compile the program to run in USER_MODE

or1k-elf-gcc -g -O2 -mhard-float -DUSER_MODE fpee.c -o fpee

or1k-elf-sim -f /opt/or1k/sim.cfg ./fpee

# Expected results with USER_MODE

# Program Header: PT_LOAD, vaddr: 0x00000000, paddr: 0x0 offset: 0x00002000, filesz: 0x000065ab, memsz: 0x000065ab

# Program Header: PT_LOAD, vaddr: 0x000085ac, paddr: 0x85ac offset: 0x000085ac, filesz: 0x000000c8, memsz: 0x0000046c

# WARNING: sim_init: Debug module not enabled, cannot start remote service to GDB

# Enabling user mode

# Exceptions enabled, now DIV 3.14 / 0!

# Got FPU Exception, PC: 0x2068

# Result: f

# FPCSR: 801

# exit(0)

In the above we can see how to compile and run a simple FPU test program and run

it on or1ksim. The program set’s up an FPU exception handler, enables exceptions

then does a divide by zero to produce an exception. This program uses the

OpenRISC newlib (baremetal) toolchain to

compile a program that can run directly on the simulator, as oppposed to a

program running in an OS on a simulator or hardware.

Note, that normally newlib programs expect to run in supervisor mode, when

our program switches to user mode we need to take some precautions to ensure it

can run correctly. As noted in the comments, usually when allocating and exiting

the newlib runtime will do things like disabling/enabling interrupts which

will fail when running in user mode.

QEMU Updates

The QEMU update was done in my

OpenRISC user space FPCSR

qemu patch series. The series was merged for the

qemu 8.1 release.

The updates were split it into three changes:

- Allowing FPCSR access in user mode.

- Properly set the exception PC address on floating point exceptions.

- Configuring the QEMU softfloat implementation to perform tininess check

before rounding.

QEMU Patch 1

The first patch to allow FPCSR access in user mode was trivial, but required some

code structure changes making the patch look bigger than it really was.

QEMU Patch 2

The next patch to properly set the exception PC address fixed a long existing

bug where the EPCR was not properly updated after FPU exceptions. Up until now

OpenRISC userspace did not support FPU instructions and this code path had not

been tested.

To explain why this fix is important let us look at the EPCR and what it is used for

in a bit more detail.

In general, when an exception occurs an OpenRISC CPU will store the program counter (PC)

of the instruction that caused the exception into the exeption program counter address

(EPCR). Floating point exceptions are a special case in that the EPCR is

actually set to the next instruction to be executed, this is to avoid looping.

When the linux kernel handles a floating point exception it follows the path

0xd00 > fpe_trap_handler > do_fpe_trap. This will setup a

signal to be delivered to the user process.

The Linux OS uses the EPCR to report the exception instruction address to

userspace via a signal which we can see being done in do_fpe_trap which

we can see below:

asmlinkage void do_fpe_trap(struct pt_regs *regs, unsigned long address)

{

int code = FPE_FLTUNK;

unsigned long fpcsr = regs->fpcsr;

if (fpcsr & SPR_FPCSR_IVF)

code = FPE_FLTINV;

else if (fpcsr & SPR_FPCSR_OVF)

code = FPE_FLTOVF;

else if (fpcsr & SPR_FPCSR_UNF)

code = FPE_FLTUND;

else if (fpcsr & SPR_FPCSR_DZF)

code = FPE_FLTDIV;

else if (fpcsr & SPR_FPCSR_IXF)

code = FPE_FLTRES;

/* Clear all flags */

regs->fpcsr &= ~SPR_FPCSR_ALLF;

force_sig_fault(SIGFPE, code, (void __user *)regs->pc);

}

Here we see the excption becomes a SIGFPE signal and the exception address in

regs->pc is passed to force_sig_fault. The PC will be used to set the

si_addr field of the siginfo_t structure.

Next upon return from kernel space to user space the path is do_fpe_trap >

_fpe_trap_handler > ret_from_exception > resume_userspace >

work_pending > do_work_pending > restore_all.

Inside of do_work_pending with there the signal handling is done. In explain a bit

about this in the article Unwinding a Bug - How C++ Exceptions Work.

In restore_all we see EPCR is returned to when exception handling is

complete. A snipped of this code is show below:

#define RESTORE_ALL \

DISABLE_INTERRUPTS(r3,r4) ;\

l.lwz r3,PT_PC(r1) ;\

l.mtspr r0,r3,SPR_EPCR_BASE ;\

l.lwz r3,PT_SR(r1) ;\

l.mtspr r0,r3,SPR_ESR_BASE ;\

l.lwz r3,PT_FPCSR(r1) ;\

l.mtspr r0,r3,SPR_FPCSR ;\

l.lwz r2,PT_GPR2(r1) ;\

l.lwz r3,PT_GPR3(r1) ;\

l.lwz r4,PT_GPR4(r1) ;\

l.lwz r5,PT_GPR5(r1) ;\

l.lwz r6,PT_GPR6(r1) ;\

l.lwz r7,PT_GPR7(r1) ;\

l.lwz r8,PT_GPR8(r1) ;\

l.lwz r9,PT_GPR9(r1) ;\

l.lwz r10,PT_GPR10(r1) ;\

l.lwz r11,PT_GPR11(r1) ;\

l.lwz r12,PT_GPR12(r1) ;\

l.lwz r13,PT_GPR13(r1) ;\

l.lwz r14,PT_GPR14(r1) ;\

l.lwz r15,PT_GPR15(r1) ;\

l.lwz r16,PT_GPR16(r1) ;\

l.lwz r17,PT_GPR17(r1) ;\

l.lwz r18,PT_GPR18(r1) ;\

l.lwz r19,PT_GPR19(r1) ;\

l.lwz r20,PT_GPR20(r1) ;\

l.lwz r21,PT_GPR21(r1) ;\

l.lwz r22,PT_GPR22(r1) ;\

l.lwz r23,PT_GPR23(r1) ;\

l.lwz r24,PT_GPR24(r1) ;\

l.lwz r25,PT_GPR25(r1) ;\

l.lwz r26,PT_GPR26(r1) ;\

l.lwz r27,PT_GPR27(r1) ;\

l.lwz r28,PT_GPR28(r1) ;\

l.lwz r29,PT_GPR29(r1) ;\

l.lwz r30,PT_GPR30(r1) ;\

l.lwz r31,PT_GPR31(r1) ;\

l.lwz r1,PT_SP(r1) ;\

l.rfe

Here we can see how l.mtspr r0,r3,SPR_EPCR_BASE restores the EPCR to the pc

address stored in pt_regs when we entered the exception handler. All

other register are restored and finally the l.rfe instruction is issued to

return from the exception which affectively jumps to EPCR.

The reason QEMU was not setting the correct exception address is due to the way

qemu is implemented which optimizes performance. QEMU executes target code

basic blocks that are translated to host native instructions, during runtime

all PC addresses are those of the host, for example x86-64 64-bit

addresses. When an exception occurs, updating the target PC address from the host PC

need to be explicityly requested.

QEMU Patch 3

The next patch to implement tininess before rouding was also trivial but

brought up a conversation about default NaN payloads.

QEMU Patch 4

Wait, there is more. During writing this article I realized that if QEMU

was setting the ECPR to the FPU instruction causing the exception then

we would end up in an endless loop.

Luckily the arcitecture anticipated this calling for FPU exceptions to set the next

instruction to be executed to EPCR. QEMU was missing this logic.

The patch target/openrisc: Set EPCR to next PC on FPE exceptions

fixes this up.

RTL Updates

Updating the actual verilog RTL CPU implementations also needed to be done.

Updates have been made to both the mor1kx

and the

or1k_marocchino

implementations.

mor1kx Updates

Updates to the mor1kx to support user mode reads and write to the FPCSR were done in the patch:

Make FPCSR is R/W accessible for both user- and supervisor- modes.

The full patch is:

@@ -618,7 +618,7 @@ module mor1kx_ctrl_cappuccino

spr_fpcsr[`OR1K_FPCSR_FPEE] <= 1'b0;

end

else if ((spr_we & spr_access[`OR1K_SPR_SYS_BASE] &

- (spr_sr[`OR1K_SPR_SR_SM] & padv_ctrl | du_access)) &&

+ (padv_ctrl | du_access)) &&

`SPR_OFFSET(spr_addr)==`SPR_OFFSET(`OR1K_SPR_FPCSR_ADDR)) begin

spr_fpcsr <= spr_write_dat[`OR1K_FPCSR_WIDTH-1:0]; // update all fields

`ifdef OR1K_FPCSR_MASK_FLAGS

The change to verilog shows that before when writng (spr_we) to the FPCSR (OR1K_SPR_FPCSR_ADDR) register

we used to check that the supervisor bit (OR1K_SPR_SR_SM) bit of the sr spr (spr_sr) is set. That check

enforced supervisor mode only write access, removing this allows user space to write to the regsiter.

Updating mor1kx to support tininess checking before rounding was done in the

change Refactoring and implementation tininess detection before

rounding.

I will not go into the details of these patches as I don’t understand them so

much.

Marocchino Updates

Updates to the or1k_marocchino to support user mode reads and write to the FPCSR were done in the patch:

Make FPCSR is R/W accessible for both user- and supervisor- modes.

The full patch is:

@@ -714,7 +714,7 @@ module or1k_marocchino_ctrl

assign except_fpu_enable_o = spr_fpcsr[`OR1K_FPCSR_FPEE];

wire spr_fpcsr_we = (`SPR_OFFSET(({1'b0, spr_sys_group_wadr_r})) == `SPR_OFFSET(`OR1K_SPR_FPCSR_ADDR)) &

- spr_sys_group_we & spr_sr[`OR1K_SPR_SR_SM];

+ spr_sys_group_we; // FPCSR is R/W for both user- and supervisor- modes

`ifdef OR1K_FPCSR_MASK_FLAGS

reg [`OR1K_FPCSR_ALLF_SIZE-1:0] ctrl_fpu_mask_flags_r;

Updating the marocchino to support dttectig tininess before rounding was done in the

patch:

Refactoring FPU Implementation for tininess detection BEFORE ROUNDING.

I will not go into details of the patch as I didn’t write them. In

general it is a medium size refactoring of the floating point unit.

Summary

We discussed updates to the architecture simulators and verilog CPU implementations

to allow supporting user mode floating point programs. These updates will now allow us to

port Linux and glibc to the OpenRISC floating point unit.

Further Reading

25 Apr 2023

Last year (2022) the big milestone for OpenRISC was getting the glibc port upstream.

Though there is libc support for

OpenRISC already with musl and ucLibc

the glibc port provides a extensive testsuite which has proved useful in shaking out toolchain

and OS bugs.

The upstreamed OpenRISC glibc support is missing support for leveraging the

OpenRISC floating-point unit (FPU).

Adding OpenRISC glibc FPU support requires a cross cutting effort across the

architecture’s fullstack from:

- Architecture Specification

- Simulators and CPU implementations

- Linux Kernel support

- GCC Instructions and Soft FPU

- Binutils/GDB Debugging Support

- glibc support

In this blog entry I will cover how the OpenRISC architecture specification

was updated to support user space floating point applications. But first, what

is FPU porting?

What is FPU Porting?

The FPU in modern CPU’s allow the processor to perform IEEE 754

floating point math like addition, subtraction, multiplication. When used in a

user application the FPU’s function becomes more of a math accelerator, speeding

up math operations including

trigonometric and

complex functions such as sin,

sinf and cexpf. Not all FPU’s provide the same

set of FPU operations nor do they have to. When enabled, the compiler will

insert floating point instructions where they can be used.

OpenRISC FPU support was added to the GCC compiler a while back.

We can see how this works with a simple example using the bare-metal newlib toolchain.

C code example addf.c:

float addf(float a, float b) {

return a + b;

}

To compile this C function we can do:

$ or1k-elf-gcc -O2 addf.c -c -o addf-sf.o

$ or1k-elf-gcc -O2 -mhard-float addf.c -c -o addf-hf.o

Assembly output of addf-sf.o contains the default software floating point

implementation as we can see below. We can see below that a call to __addsf3 was

added to perform our floating point operation. The function __addsf3

is provided

by libgcc as a software implementation of the single precision

floating point (sf) add operation.

$ or1k-elf-objdump -dr addf-sf.o

Disassembly of section .text:

00000000 <addf>:

0: 9c 21 ff fc l.addi r1,r1,-4

4: d4 01 48 00 l.sw 0(r1),r9

8: 04 00 00 00 l.jal 8 <addf+0x8>

8: R_OR1K_INSN_REL_26 __addsf3

c: 15 00 00 00 l.nop 0x0

10: 85 21 00 00 l.lwz r9,0(r1)

14: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

18: 9c 21 00 04 l.addi r1,r1,4

The disassembly of the addf-hf.o below shows that the FPU instruction

(hardware) lf.add.s is used to perform addition, this is because the snippet

was compiled using the -mhard-float argument. One could imagine if this is

supported it would be more efficient compared to the software implementation.

$ or1k-elf-objdump -dr addf-hf.o

Disassembly of section .text:

00000000 <addf>:

0: c9 63 20 00 lf.add.s r11,r3,r4

4: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

8: 15 00 00 00 l.nop 0x0

So if the OpenRISC toolchain already has support for FPU instructions what else

needs to be done? When we add FPU support to glibc we are adding FPU support

to the OpenRISC POSIX runtime and create a toolchain that can compile and link

binaries to run on this runtime.

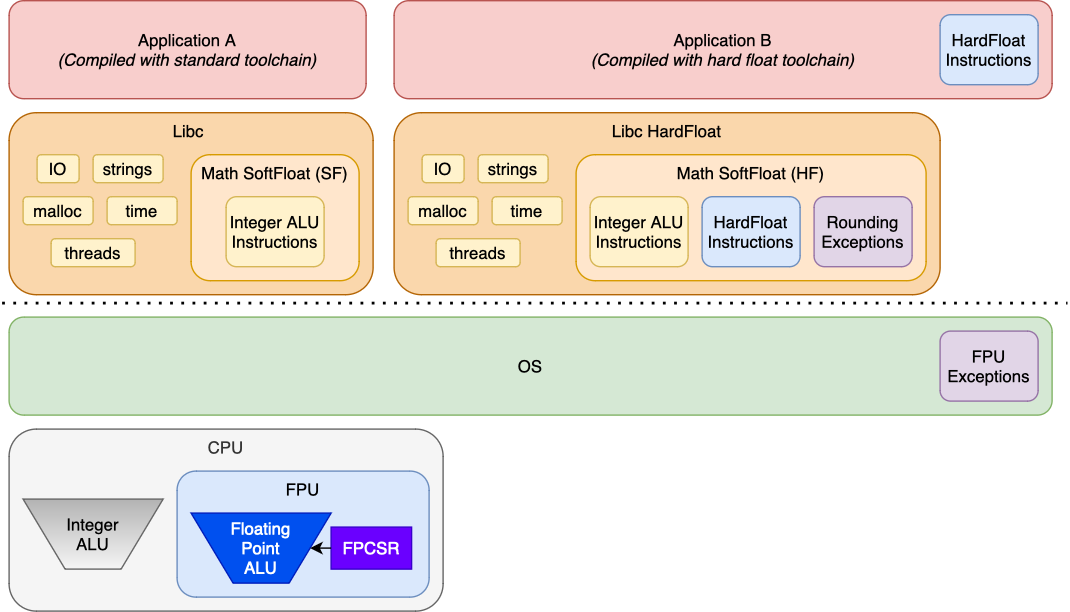

The Runtime

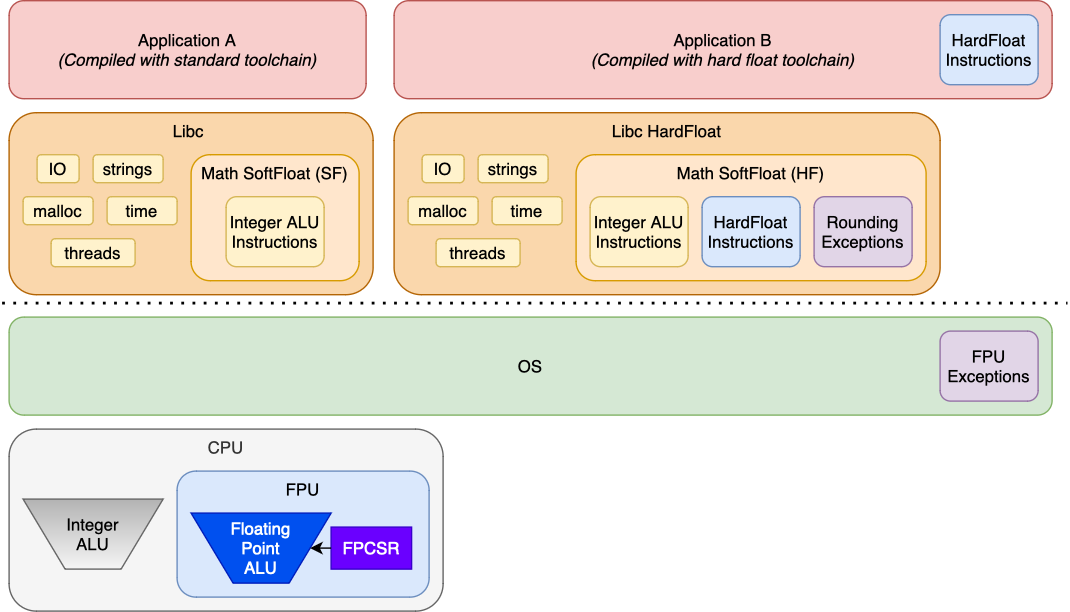

Below we can see examples of two application runtimes, one Application A runs

with software floating point, the other Application B run’s with full hardware

floating point.

Both Application A and Application B can run on the same system, but

Application B requires a libc and kernel that support the floating point

runtime. As we can see:

- In Application B it leverages floating point instructions as noted in the

blue box. That should be implemented in the

CPU, and are produced by the GCC compiler.

- The math routines in the C Library used by Application B are accelarated by

the FPU as per the blue box. The math routines can also set up rounding of the FPU hardware to

be in line with rounding of the software routines. The math routines can

also detect exceptions by checking the FPU state. The rounding and exception

handling in the purple boxes is what is

implemented the GLIBC.

- The kernel must be able to save and restore the FPU state when switching

between processes. The OS also has support for signalling the process if

enabled. This is indicated in the purple

box.

Another aspect is that supporting hardware floating point in the OS means that

multiple user land programs can transparently use the FPU. To do all of this we

need to update the kernel and the C runtime libraries to:

- Make the kernel save and restore process FPU state during context switches

- Make the kernel handle FPU exceptions and deliver signals to user land

- Teach GLIBC how to setup FPU rounding mode

- Teach GLIBC how to translate FPU exceptions

- Tell GCC and GLIBC soft float about our FPU quirks

In order to compile applications like Application B a separate compiler

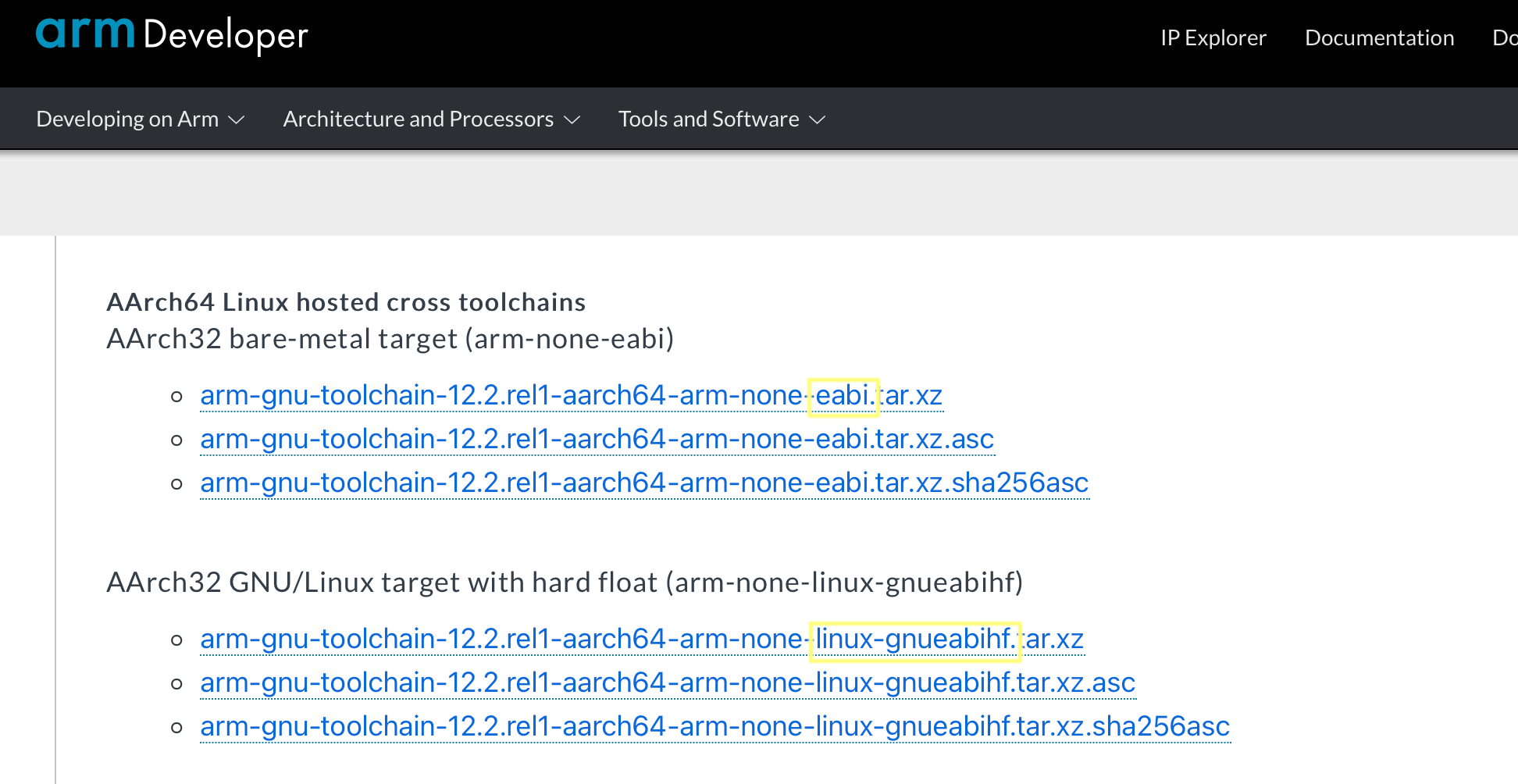

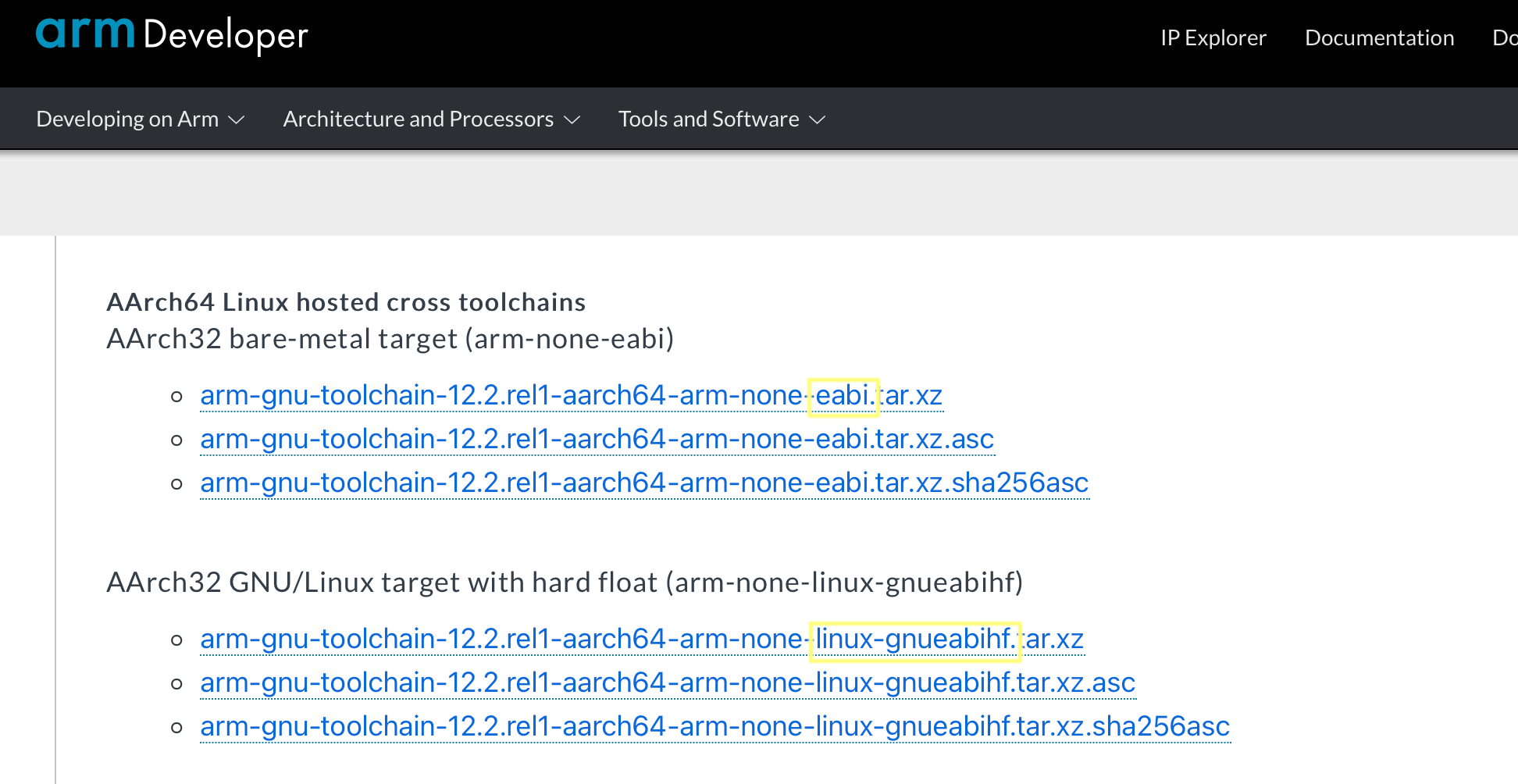

toolchain is needed. For highly configurable embredded system CPU’s like ARM, RISC-V there

are multiple toolchains available for building software for the different CPU

configurations. Usually there will be one toolchain for soft float and one for hard float support, see the below example

from the arm toolchain download page.

Fixing Architecture Issues

As we started to work on the floating point support we found two issues:

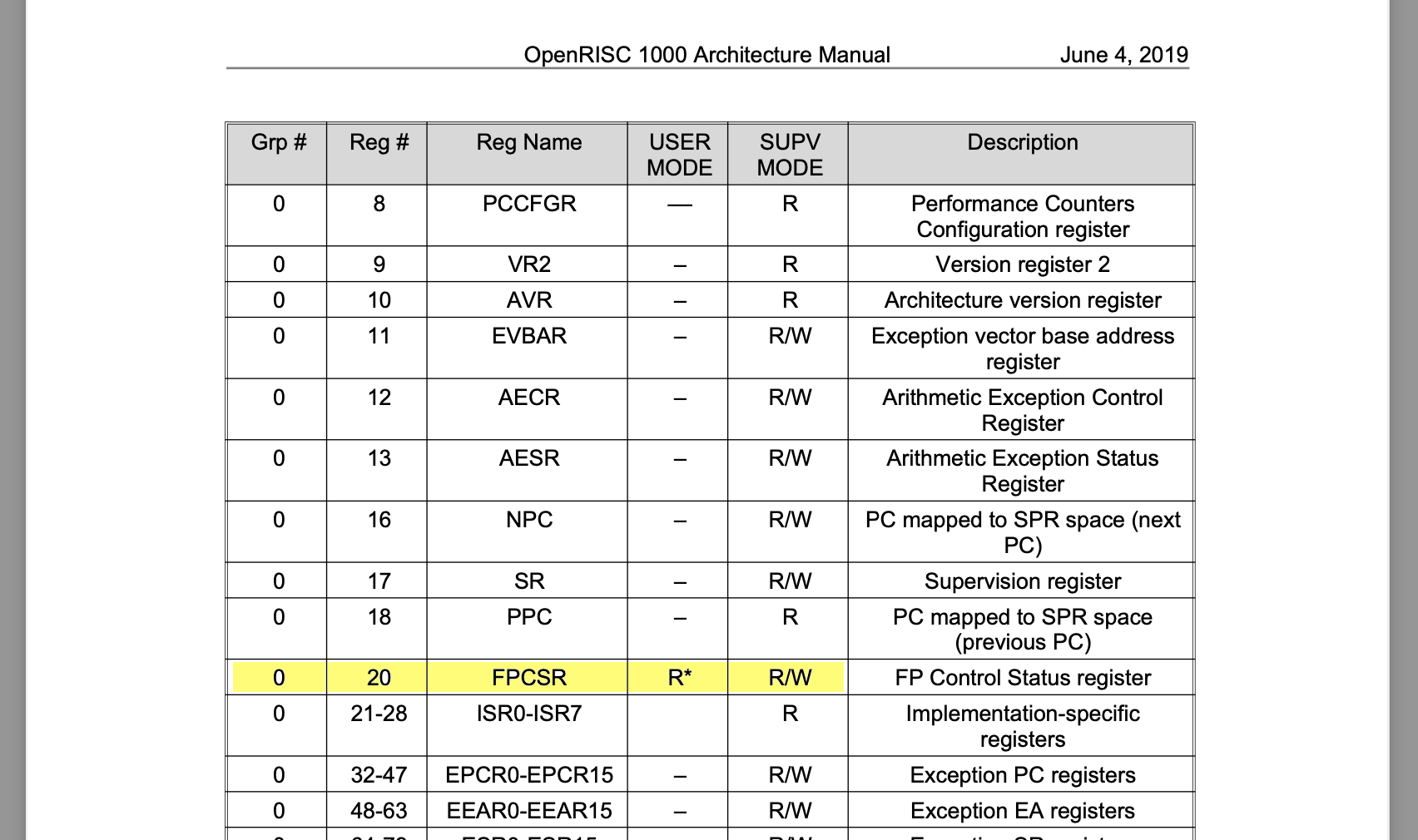

- The OpenRISC floating point control and status register (FPCSR) is accessible only in

supervisor mode.

- We have not defined how the FPU should perform tininess detection.

FPCSR Access

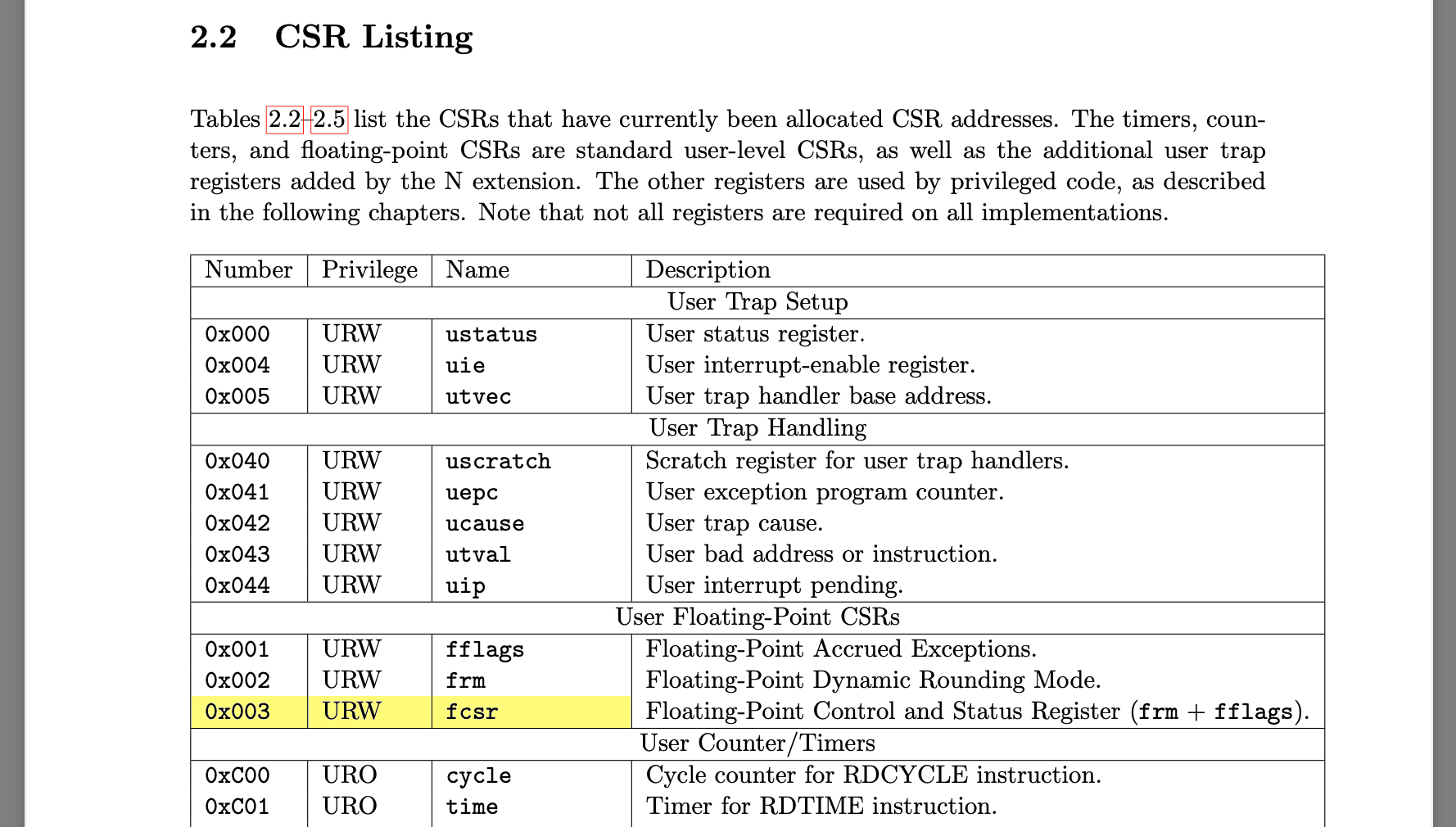

The GLIBC OpenRISC FPU port, or any port for that matter, starts

by looking at what other architectures have done. For GLIBC FPU support we can

look at what MIPS, ARM, RISC-V etc. have implemented. Most ports have a file

called sysdeps/{arch}/fpu_control.h, I noticed one thing right away as I went

through this, we can look at ARM or MIPS for example:

sysdeps/mips/fpu_control.h:

Excerpt from the MIPS port showing the definition of _FPU_GETCW and _FPU_SETCW

#else

# define _FPU_GETCW(cw) __asm__ volatile ("cfc1 %0,$31" : "=r" (cw))

# define _FPU_SETCW(cw) __asm__ volatile ("ctc1 %0,$31" : : "r" (cw))

#endif

sysdeps/arm/fpu_control.h:

Excerpt from the ARM port showing the definition of _FPU_GETCW and _FPU_SETCW

# define _FPU_GETCW(cw) \

__asm__ __volatile__ ("vmrs %0, fpscr" : "=r" (cw))

# define _FPU_SETCW(cw) \

__asm__ __volatile__ ("vmsr fpscr, %0" : : "r" (cw))

#endif

What we see here is a macro that defines how to read or write the floating point

control word for each architecture. The macros are implemented using a single

assembly instruction.

In OpenRISC we have similar instructions for reading and writing the floating

point control register (FPCSR), writing for example is: l.mtspr r0,%0,20. However,

on OpenRISC the FPCSR is read-only when running in user-space, this is a

problem.

If we remember from our operating system studies, user applications run in

user-mode as

apposed to the privileged kernel-mode.

The user floating point environment

is defined by POSIX in the ISO C Standard. The C library provides functions to

set rounding modes and clear exceptions using for example

fesetround

for setting FPU rounding modes and

feholdexcept for clearing exceptions.

If userspace applications need to be able to control the floating point unit

the having architectures support for this is integral.

Originally OpenRISC architecture specification

specified the floating point control and status registers (FPCSR) as being

read only when executing in user mode, again this is a problem and needs to

be addressed.

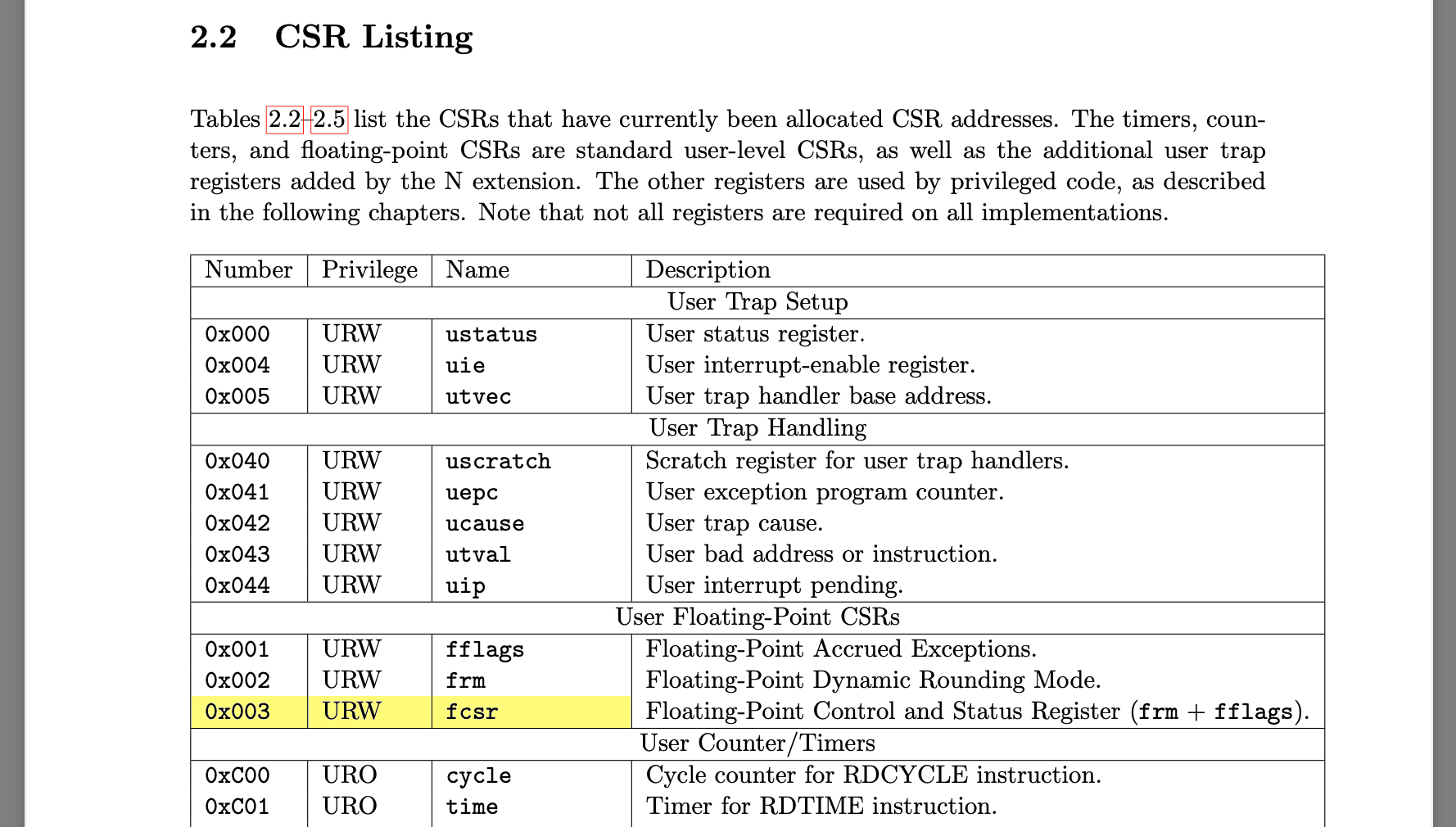

Other architectures define the floating point control register as being writable in user-mode.

For example, ARM has the

FPCR and FPSR,

and RISC-V has the

FCSR

all of which are writable in user-mode.

Tininess Detection

I am skipping ahead a bit here, once the OpenRISC GLIBC port was working we noticed

many problematic math test failures. This turned out to be inconsistencies

between the tininess detection [pdf]

settings in the toolchain. Tininess detection must be selected by an FPU

implementation as being done before or after rounding.

In the toolchain this is configured by:

- GLIBC

TININESS_AFTER_ROUNDING - macro used by test suite to control

expectations

- GLIBC

_FP_TININESS_AFTER_ROUNDING - macro used to control softfloat

implementation in GLIBC.

- GCC libgcc

_FP_TININESS_AFTER_ROUNDING - macro used to control softfloat

implementation in GCC libgcc.

Updating the Spec

Writing to FPCSR from user-mode could be worked around in OpenRISC by

introducing a syscall, but we decided to just change the architecture

specification for this. Updating the spec keeps it similar to all other

architectures out there.

In OpenRISC we have defined tininess detection to be done before rounding as

this matches what existing FPU implementation have done.

As of architecture specification revision

1.4 the FPCSR is defined as being writable

in user-mode and we have documented tininess detection to be before rounding.

Summary

We’ve gone through an overview of how the FPU accelarates math in

an application runtime. We then looked how the OpenRISC architecture specification needed

to be updated to support the floating point POSIX runtime.

In the next entry we shall look into patches to get QEMU and and CPU

implementations updated to support the new spec changes.

13 Dec 2020

I have been working on porting GLIBC to the OpenRISC architecture. This has

taken longer than I expected as with GLIBC upstreaming we must get every

test to pass. This was different compared to GDB and GCC which were a

bit more lenient.

My first upstreaming attempt

was completely tested on the QEMU simulator. I have

since added an FPGA LiteX SoC

to my test platform options. LiteX runs Linux on the OpenRISC mor1kx softcore

and tests are loaded over an SSH session. The SoC eliminates an issue I was

seeing on the simulator where under heavy load it appears the MMU starves the kernel

from getting any work done.

To get to where I am now this required:

Adding GDB Linux debugging support is great because it allows debugging of

multithreaded processes and signal handling; which we are going to need.

A Bug

Our story starts when I was trying to fix a failing GLIBC NPTL

test case. The test case involves C++ exceptions and POSIX threads.

The issue is that the catch block of a try/catch block is not

being called. Where do we even start?

My plan for approaching test case failures is:

- Understand what the test case is trying to test and where its failing

- Create a hypothesis about where the problem is

- Understand how the failing API’s works internally

- Debug until we find the issue

- If we get stuck go back to

2.

Let’s have a try.

Understanding the Test case

The GLIBC test case is nptl/tst-cancel24.cc.

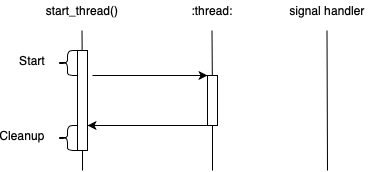

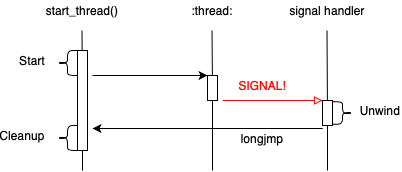

The test starts in the do_test function and it will create a child thread with pthread_create.

The child thread executes function tf which waits on a semaphore until the parent thread cancels it. It

is expected that the child thread, when cancelled , will call it’s catch block.

The failure is that the catch block is not getting run as evidenced by the except_caught variable

not being set to true.

Below is an excerpt from the test showing the tf function.

static void *

tf (void *arg) {

sem_t *s = static_cast<sem_t *> (arg);

try {

monitor m;

pthread_barrier_wait (&b);

while (1)

sem_wait (s);

} catch (...) {

except_caught = true;

throw;

}

return NULL;

}

So the catch block is not being run. Simple, but where do we start to

debug that? Let’s move onto the next step.

Creating a Hypothesis

This one is a bit tricky as it seems C++ try/catch blocks are broken. Here, I am

working on GLIBC testing, what does that have to do with C++?

To get a better idea of where the problem is I tried to modify the test to test

some simple ideas. First, maybe there is a problem with catching exceptions

throws from thread child functions.

static void do_throw() { throw 99; }

static void * tf () {

try {

monitor m;

while (1) do_throw();

} catch (...) {

except_caught = true;

}

return NULL;

}

No, this works correctly. So try/catch is working.

Hypothesis: There is a problem handling exceptions while in a syscall.

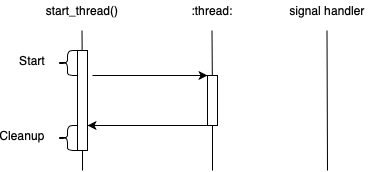

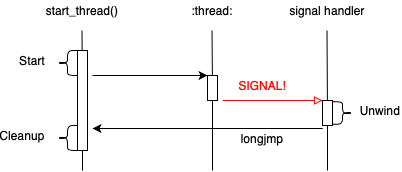

There may be something broken with OpenRISC related to how we setup stack

frames for syscalls that makes the unwinder fail.