Recently I have been working on getting the OpenRISC glibc port ready for upstreaming. Part of this work has been to run the glibc testsuite and get the tests to pass. The glibc testsuite has a comprehensive set of linker and runtime relocation tests.

In order to fix issues with tests I had to learn more than I did before about ELF Relocations , Thread Local Storage and the binutils linker implementation in BFD. There is a lot of documentation available, but it’s a bit hard to follow as it assumes certain knowledge, for example have a look at the Solaris Linker and Libraries section on relocations. In this article I will try to fill in those gaps.

This will be an illustrated 3 part series covering

- ELF Binaries and Relocation Entries

- Thread Local Storage

- How Relocations and Thread Local Store are Implemented

All of the examples in this article can be found in my tls-examples project. Please check it out.

On Linux, you can download it and make it with your favorite toolchain.

By default it will cross compile using an openrisc toolchain.

This can be overridden with the CROSS_COMPILE variable.

For example, to build for your current host.

$ git clone git@github.com:stffrdhrn/tls-examples.git

$ make CROSS_COMPILE=

gcc -fpic -c -o tls-gd-dynamic.o tls-gd.c -Wall -O2 -g

gcc -fpic -c -o nontls-dynamic.o nontls.c -Wall -O2 -g

...

objdump -dr x-static.o > x-static.S

objdump -dr xy-static.o > xy-static.S

Now we can get started.

ELF Segments and Sections

Before we can talk about relocations we need to talk a bit about what makes up ELF binaries. This is a prerequisite as relocations and TLS are part of ELF binaries. There are a few basic ELF binary types:

- Objects (

.o) - produced by a compiler, contains a collection of sections, also call relocatable files. - Program - an executable program, contains sections grouped into segments.

- Shared Objects (

.so) - a program library, contains sections grouped into segments. - Core Files - core dump of program memory, these are also ELF binaries

Here we will discuss Object Files and Program Files.

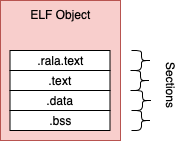

An ELF Object

The compiler generates object files, these contain sections of binary data and these are not executable.

The object file produced by gcc

generally contains .rela.text, .text, .data and .bss sections.

.rela.text- a list of relocations against the.textsection.text- contains compiled program machine code.data- static and non static initialized variable values.bss- static and non static non-initialized variables

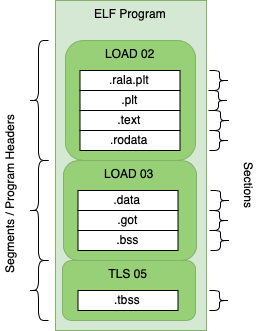

An ELF Program

ELF binaries are made of sections and segments.

A segment contains a group of sections and the segment defines how the data should be loaded into memory for program execution.

Each segment is mapped to program memory by the kernel when a process is created. Program files contain most of the same sections as objects but there are some differences.

.text- contains executable program code, there is no.rela.textsection.got- the global offset table used to access variables, created during link time. May be populated during runtime.

Looking at ELF binaries (readelf)

The readelf tool can help inspect elf binaries.

Some examples:

Reading Sections of an Object File

Using the -S option we can read sections from an elf file.

As we can see below we have the .text, .rela.text, .bss and many other

sections.

$ readelf -S tls-le-static.o

There are 20 section headers, starting at offset 0x604:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 00000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 00000000 000034 000020 00 AX 0 0 4

[ 2] .rela.text RELA 00000000 0003f8 000030 0c I 17 1 4

[ 3] .data PROGBITS 00000000 000054 000000 00 WA 0 0 1

[ 4] .bss NOBITS 00000000 000054 000000 00 WA 0 0 1

[ 5] .tbss NOBITS 00000000 000054 000004 00 WAT 0 0 4

[ 6] .debug_info PROGBITS 00000000 000054 000074 00 0 0 1

[ 7] .rela.debug_info RELA 00000000 000428 000084 0c I 17 6 4

[ 8] .debug_abbrev PROGBITS 00000000 0000c8 00007c 00 0 0 1

[ 9] .debug_aranges PROGBITS 00000000 000144 000020 00 0 0 1

[10] .rela.debug_arang RELA 00000000 0004ac 000018 0c I 17 9 4

[11] .debug_line PROGBITS 00000000 000164 000087 00 0 0 1

[12] .rela.debug_line RELA 00000000 0004c4 00006c 0c I 17 11 4

[13] .debug_str PROGBITS 00000000 0001eb 00007a 01 MS 0 0 1

[14] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 000265 00002b 01 MS 0 0 1

[15] .debug_frame PROGBITS 00000000 000290 000030 00 0 0 4

[16] .rela.debug_frame RELA 00000000 000530 000030 0c I 17 15 4

[17] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 0002c0 000110 10 18 15 4

[18] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 0003d0 000025 00 0 0 1

[19] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 000560 0000a1 00 0 0 1

Reading Sections of a Program File

Using the -S option on a program file we can also read the sections. The file

type does not matter as long as it is an ELF we can read the sections.

As we can see below there is no longer a rela.text section, but we have others

including the .got section.

$ readelf -S tls-le-static

There are 31 section headers, starting at offset 0x32e8fc:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 00000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 000020d4 0000d4 080304 00 AX 0 0 4

[ 2] __libc_freeres_fn PROGBITS 000823d8 0803d8 001118 00 AX 0 0 4

[ 3] .rodata PROGBITS 000834f0 0814f0 01544c 00 A 0 0 4

[ 4] __libc_subfreeres PROGBITS 0009893c 09693c 000024 00 A 0 0 4

[ 5] __libc_IO_vtables PROGBITS 00098960 096960 0002f4 00 A 0 0 4

[ 6] __libc_atexit PROGBITS 00098c54 096c54 000004 00 A 0 0 4

[ 7] .eh_frame PROGBITS 00098c58 096c58 0027a8 00 A 0 0 4

[ 8] .gcc_except_table PROGBITS 0009b400 099400 000089 00 A 0 0 1

[ 9] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 0009b48c 09948c 000020 00 A 0 0 4

[10] .tdata PROGBITS 0009dc28 099c28 000010 00 WAT 0 0 4

[11] .tbss NOBITS 0009dc38 099c38 000024 00 WAT 0 0 4

[12] .init_array INIT_ARRAY 0009dc38 099c38 000004 04 WA 0 0 4

[13] .fini_array FINI_ARRAY 0009dc3c 099c3c 000008 04 WA 0 0 4

[14] .data.rel.ro PROGBITS 0009dc44 099c44 0003bc 00 WA 0 0 4

[15] .data PROGBITS 0009e000 09a000 000de0 00 WA 0 0 4

[16] .got PROGBITS 0009ede0 09ade0 000064 04 WA 0 0 4

[17] .bss NOBITS 0009ee44 09ae44 000bec 00 WA 0 0 4

[18] __libc_freeres_pt NOBITS 0009fa30 09ae44 000014 00 WA 0 0 4

[19] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 09ae44 00002a 01 MS 0 0 1

[20] .debug_aranges PROGBITS 00000000 09ae6e 002300 00 0 0 1

[21] .debug_info PROGBITS 00000000 09d16e 0fd048 00 0 0 1

[22] .debug_abbrev PROGBITS 00000000 19a1b6 0270ca 00 0 0 1

[23] .debug_line PROGBITS 00000000 1c1280 0ce95c 00 0 0 1

[24] .debug_frame PROGBITS 00000000 28fbdc 0063bc 00 0 0 4

[25] .debug_str PROGBITS 00000000 295f98 011e35 01 MS 0 0 1

[26] .debug_loc PROGBITS 00000000 2a7dcd 06c437 00 0 0 1

[27] .debug_ranges PROGBITS 00000000 314204 00c900 00 0 0 1

[28] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 320b04 0075d0 10 29 926 4

[29] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 3280d4 0066ca 00 0 0 1

[30] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 32e79e 00015c 00 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

p (processor specific)

Reading Segments from a Program File

Using the -l option on a program file we can read the segments.

Notice how segments map from file offsets to memory offsets and alignment.

The two different LOAD type segments are segregated by read only/execute and read/write.

Each section is also mapped to a segment here. As we can see .text is in the first LOAD` segment

which is executable as expected.

$ readelf -l tls-le-static

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x2104

There are 5 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

LOAD 0x000000 0x00002000 0x00002000 0x994ac 0x994ac R E 0x2000

LOAD 0x099c28 0x0009dc28 0x0009dc28 0x0121c 0x01e1c RW 0x2000

NOTE 0x09948c 0x0009b48c 0x0009b48c 0x00020 0x00020 R 0x4

TLS 0x099c28 0x0009dc28 0x0009dc28 0x00010 0x00034 R 0x4

GNU_RELRO 0x099c28 0x0009dc28 0x0009dc28 0x003d8 0x003d8 R 0x1

Section to Segment mapping:

Segment Sections...

00 .text __libc_freeres_fn .rodata __libc_subfreeres __libc_IO_vtables __libc_atexit .eh_frame .gcc_except_table .note.ABI-tag

01 .tdata .init_array .fini_array .data.rel.ro .data .got .bss __libc_freeres_ptrs

02 .note.ABI-tag

03 .tdata .tbss

04 .tdata .init_array .fini_array .data.rel.ro

Reading Segments from an Object File

Using the -l option with an object file does not work as we can see below.

readelf -l tls-le-static.o

There are no program headers in this file.

Relocation entries

As mentioned an object file by itself is not executable. The main reason is that

there are no program headers as we just saw. Another reason is that

the .text section still contains relocation entries (or placeholders) for the

addresses of variables located in the .data and .bss sections.

These placeholders will just be 0 in the machine code. So, if we tried to run

the machine code in an object file we would end up with Segmentation faults (SEGV).

A relocation entry is a placeholder that is added by the compiler or linker when

producing ELF binaries.

The relocation entries are to be filled in with addresses pointing to data.

Relocation entries can be made in code such as the .text section or in data

sections like the .got section. For example:

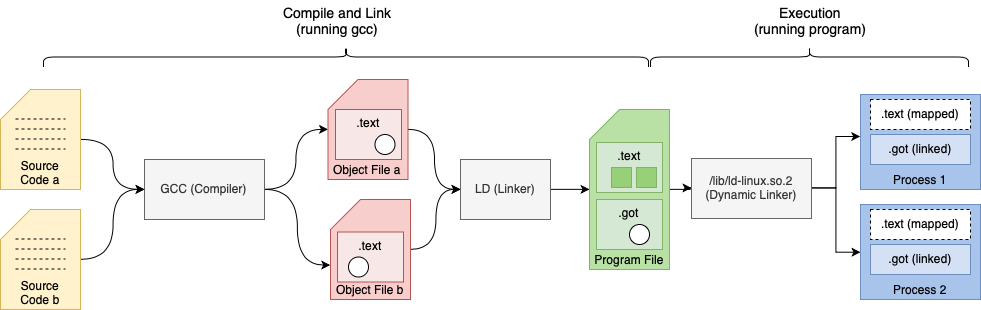

Resolving Relocations

The diagram above shows relocation entries as white circles. Relocation entries may be filled or resolved at link-time or dynamically during execution.

Link time relocations

- Place holders are filled in when ELF object files are linked by the linker to create executables or libraries

- For example, relocation entries in

.textsections

Dynamic relocations

- Place holders is filled during runtime by the dynamic linker. i.e. Procedure Link Table

- For example, relocation entries added to

.gotand.pltsections which link to shared objects.

Note: Statically built binaries do not have any dynamic relocations and are not loaded with the dynamic linker.

In general link time relocations are used to fill in relocation entries in code. Dynamic relocations fill in relocation entries in data sections.

Listing Relocation Entries

A list of relocations in a ELF binary can printed using readelf with

the -r options.

Output of readelf -r tls-gd-dynamic.o

Relocation section '.rela.text' at offset 0x530 contains 10 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym.Value Sym. Name + Addend

00000000 00000f16 R_OR1K_TLS_GD_HI1 00000000 x + 0

00000008 00000f17 R_OR1K_TLS_GD_LO1 00000000 x + 0

00000020 0000100c R_OR1K_GOTPC_HI16 00000000 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ - 4

00000024 0000100d R_OR1K_GOTPC_LO16 00000000 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ + 0

0000002c 00000d0f R_OR1K_PLT26 00000000 __tls_get_addr + 0

...

The relocation entry list explains how to and where to apply the relocation entry. It contains:

Offset- the location in the binary that needs to be updatedInfo- the encoded value containing theType, Sym and Addend, which is broken down to:Type- the type of relocation (the formula for what is to be performed is defined in the linker)Sym. Value- the address value (if known) of the symbol.Sym. Name- the name of the symbol (variable name) that this relocation needs to find during link time.

Addend- a value that needs to be added to the derived symbol address. This is used to with arrays (i.e. for a relocation referencinga[14]we would have Sym. Nameaand an Addend of the data size ofatimes14)

Example

File: nontls.c

In the example below we have a simple variable and a function to access it’s address.

static int x;

int* get_x_addr() {

return &x;

}

Let’s see what happens when we compile this source.

The steps to compile and link can be found in the tls-examples project hosting the source examples.

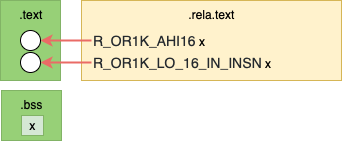

Before Linking

The diagram above shows relocations in the resulting object file as white circles.

In the actual output below we can see that access to the variable x is

referenced by a literal 0 in each instruction. These are highlighted with

square brackets [] below for clarity.

These empty parts of the .text section are relocation entries.

Addr. Machine Code Assembly Relocations

0000000c <get_x_addr>:

c: 19 60 [00 00] l.movhi r11,[0] # c R_OR1K_AHI16 .bss

10: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

14: 9d 6b [00 00] l.addi r11,r11,[0] # 14 R_OR1K_LO_16_IN_INSN .bss

The function get_x_addr will return the address of variable x.

We can look at the assembly instruction to understand how this is done. Some background

of the OpenRISC ABI.

- Registers are 32-bit.

- Function return values are placed in register

r11. - To return from a function we jump to the address in the link register

r9. - OpenRISC has a branch delay slot, meaning the address after a branch it executed before the branch is taken.

Now, lets break down the assembly:

l.movhi- move the value[0]into high bits of registerr11, clearing the lower bits.l.addi- add the value in registerr11to the value[0]and store the results inr11.l.jr- jump to the address inr9

This constructs a 32-bit value out of 2 16-bit values.

After Linking

The diagram above shows the relocations have been replaced with actual values.

As we can see from the linker output the places in the machine code that had relocation place holders

are now replaced with values. For example 1a 20 00 00 has become 1a 20 00 0a.

00002298 <get_x_addr>:

2298: 19 60 00 0a l.movhi r11,0xa

229c: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9

22a0: 9d 6b ee 60 l.addi r11,r11,-4512

If we calculate 0xa << 16 + -4512 (fee60) we see get 0009ee60. That is the

same location of x within our binary. This we can check with readelf -s

which lists all symbols.

$ readelf -s nontls-static | grep ' x'

42: 0009ee60 4 OBJECT LOCAL DEFAULT 17 x

Types of Relocations

As we saw above, a simple program resulted in 2 different relocation entries just to compose the address of 1 variable. We saw:

R_OR1K_AHI16R_OR1K_LO_16_IN_INSN

The need for different relacation types comes from the different requirements for the relocation. Processing of a relocation involves usually a very simple transform , each relocation defines a different transform. The components of the relocation definition are:

- Input The input of a relocation formula is always the Symbol Address who’s absolute value is unknown at compile time. But

there may also be other input variables to the formula including:

- Program Counter The absolute address of the machine code address being updated

- Addend The addend from the relocation entry discussed above in the Listing Relocation Entries section

- Formula How the input is manipulated to derive the output value. For example shift right 16 bits.

- Bit-Field Specifies which bits at the output address need to be updated.

To be more specific about the above relocations we have:

| Relocation Type | Bit-Field | Formula |

|---|---|---|

R_OR1K_AHI16 |

simm16 |

S >> 16 |

R_OR1K_LO_16_IN_INSN |

simm16 |

S && 0xffff |

The Bit-Field described above is simm16 which means update the lower 16-bits

of the 32-bit value at the output offset and do not disturb the upper 16-bits.

+----------+----------+

| | simm16 |

| 31 16 | 15 0 |

+----------+----------+

There are many other Relocation Types with difference Bit-Fields and Formulas. These use different methods based on what each instruction does, and where each instruction encodes its immediate value.

For full listings refer to architecture manuals.

- Linkers and Libraries - Oracle’s documentation on Intel and Sparc relocations

- Binutils OpenRISC Relocs - Binutil Manual containing details on OpenRISC relocations

- ELF for ARM[pdf] - ARM Relocation Types table on page 25

Take a look and see if you can understand how to read these now.

Summary

In this article we have discussed what ELF binaries are and how they can be read. We have talked about how from compilation to linking to runtime, relocation entries are used to communicate which parts of a program remain to be resolved. We then discussed how relocation types provide a formula and bit-mask for updating the places in ELF binaries that need to be filled in.

In the next article we will discuss how Thread Local Storage works, both link-time and runtime relocation entries play big part in how TLS works.

Further Reading

- Bottums Up - Dynamic Linker - Details on the Dynamic Linker, Relocations and Position Independent Code

- GOT and PLT Key to Code Sharing - Good overview of the

.gotand.pltsections