What I learned from doing the OpenRISC GCC port, a deep dive into passes

When starting the OpenRISC gcc port I had a good idea of how the compiler worked and what would be involved in the port. Those main things being

- define a new machine description file in gcc’s RTL

- define a bunch of description macros and helper functions in a

.cand.hfile.

I realized early on that trouble shooting issues requires understanding the purpose of some important compiler passes. It was difficult to understand what all of the compiler passes were. There are so many, 200+, but after some time I found there are a few key passes to be concerned about; lets jump in.

Quick Tips

- When debugging compiler problems use the

-fdump-rtl-all-alland-fdump-tree-all-allflags to debug where things go wrong. - To understand which passes are run for different

-Onoptimization levels you can use-fdump-passes. - The numbers in the dump output files indicate the order in which passes were run. For

example between

test.c.235r.vregsandtest.c.234r.expandthe expand pass is run before vregs, and there were no passes run inbetween. - The debug options

-S -dpare also helpful for tying RTL up with the output assembly. The-Soption tells the compiler to dump the assembler output, and-dpenables annotation comments showing the RTL instruction id, name and other useful statistics.

Glossary Terms

- We may see

cfgthoughout the gcc source, this is not configuration, but control flow graph. Spillingis performed when there are not enough registers available during register allocation to store all scope variables, one variable in a register is chosen andspilledby saving it to memory; thus freeing up a register for allocation.ILis a GCC intermediate language i.e. GIMPLE or RTL. During porting we are mainly concerned with RTL.Loweringare operations done by passes to take higher level language and graph representations and make them more simple/lower level in preparation for machine assembly conversion.Predicatespart of theRTLthese are used to facilitate instruction matching the. Having these more specific reduces the work that reload needs to do and generates better code.Constraintspart of theRTLand used during reload, these are associated with assembly instructions used to resolved the target instruction.

Passes

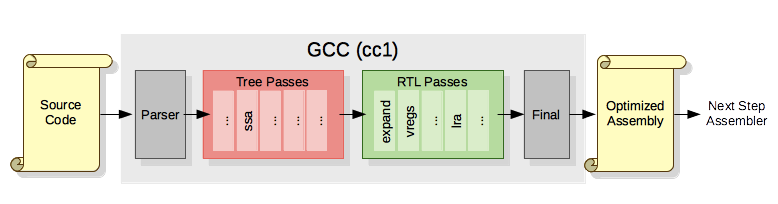

Passes are the core of the compiler. To start, there are basically two types of compiler passes in gcc:

- Tree - Passes working on GIMPLE.

- RTL - Passes working on Register Transfer Language.

There are also Interprocedural analysis passes (IPA) which we will not get into, as I don’t really know what they are. You can find a list of all passes in gcc/passes.def.

In this post we will concentrate on the RTL passes as this is what most of our backend port influences. The passes interesting for our port are:

- expand

- vregs

- split

- combine

- ira

- LRA/reload

An Example

In order to illustrate how the passes work we have the following example C

snippet of code. We will compile it and inspect the output of each stage.

int func (int a, int b) {

return 2 * a + b;

}When compiled with or1k-elf-gcc -O0 -c ../func.c the output is:

$ or1k-elf-objdump -dr func.o

func.o: file format elf32-or1k

Disassembly of section .text:

00000000 <func>:

0: 9c 21 ff f0 l.addi r1,r1,-16 ; Adjust stack pointer

4: d4 01 10 08 l.sw 8(r1),r2 ; Save old frame pointer

8: 9c 41 00 10 l.addi r2,r1,16 ; Adjust frame pointer

c: d4 01 48 0c l.sw 12(r1),r9 ; Save link register

10: d7 e2 1f f0 l.sw -16(r2),r3 ; Store arg[0]

14: d7 e2 27 f4 l.sw -12(r2),r4 ; Store arg[1]

18: 86 22 ff f0 l.lwz r17,-16(r2) ; Load arg[1]

1c: e2 31 88 00 l.add r17,r17,r17

20: e2 71 88 04 l.or r19,r17,r17

24: 86 22 ff f4 l.lwz r17,-12(r2) ; Load arg[0]

28: e2 33 88 00 l.add r17,r19,r17

2c: e1 71 88 04 l.or r11,r17,r17

30: 84 41 00 08 l.lwz r2,8(r1) ; Restore old frame pointer

34: 85 21 00 0c l.lwz r9,12(r1) ; Restore link register

38: 9c 21 00 10 l.addi r1,r1,16 ; Restore old stack pointer

3c: 44 00 48 00 l.jr r9 ; Return

40: 15 00 00 00 l.nop 0x0

Lets walk though some of the RTL passes to understand how we arrived at the above.

The Expand Pass

During passes there is a sudden change from GIMPLE to RTL, this change happens during expand/rtl generation pass.

There are about 55,000 lines of code used to handle expand.

1094 gcc/stmt.c - expand_label, expand_case

5929 gcc/calls.c - expand_call

12054 gcc/expr.c - expand_assignment, expand_expr_addr_expr ...

2270 gcc/explow.c

6168 gcc/expmed.c - expand_shift, expand_mult, expand_and ...

6817 gcc/function.c - expand_function_start, expand_function_end

7327 gcc/optabs.c - expand_binop, expand_doubleword_shift, expand_float, expand_atomic_load ...

6641 gcc/emit-rtl.c

6631 gcc/cfgexpand.c - pass and entry poiint is defined herei expand_gimple_stmt

54931 total

The expand pass is defined in gcc/cfgexpand.c.

It will take the instruction names like addsi3 and movsi and expand them to

RTL instructions which will be refined by further passes.

Expand Input

Before RTL generation we have GIMPLE. Below is the content of func.c.232t.optimized the last

of the tree passes before RTL conversion.

An important tree pass is Static Single Assignment

(SSA) I don’t go into it here, but it is what makes us have so many variables, note that

each variable will be assigned only once, this helps simplify the tree for analysis

and later RTL steps like register allocation.

func (intD.1 aD.1448, intD.1 bD.1449)

{

intD.1 a_2(D) = aD.1448;

intD.1 b_3(D) = bD.1449;

intD.1 _1;

intD.1 _4;

_1 = a_2(D) * 2;

_4 = _1 + b_3(D);

return _4;

}Expand Output

After expand we can first see the RTL. Each statement of the gimple above will

be represented by 1 or more RTL expressions. I have simplified the RTL a bit and

included the GIMPLE inline for clarity.

Tip Reading RTL. RTL is a lisp dialect. Each statement has the form (type id prev next n (statement)).

(insn 2 5 3 2 (set (reg/v:SI 44) (reg:SI 3 r3)) (nil))

For the instruction:

insnis the expression type2is the instruction unique id5is the instruction before it3is the next instruction2I am not sure what this is(set (reg/v:SI 44) (reg:SI 3 r3)) (nil)- is the expression

Back to our example, this is with -O0 to allow the virtual-stack-vars to not

be elimated for verbosity:

This is the contents of func.c.234r.expand.

;; func (intD.1 aD.1448, intD.1 bD.1449)

;; {

;; Note: First we save the arguments

;; intD.1 a_2(D) = aD.1448;

(insn 2 5 3 2 (set (mem/c:SI (reg/f:SI 36 virtual-stack-vars) [1 a+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 3 r3 [ a ])) "../func.c":1 -1

(nil))

;; intD.1 b_3(D) = bD.1449;

(insn 3 2 4 2 (set (mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 36 virtual-stack-vars)

(const_int 4 [0x4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 4 r4 [ b ])) "../func.c":1 -1

(nil))

;; Note: this was optimized from x 2 to n + n.

;; _1 = a_2(D) * 2;

;; This is expanded to:

;; 1. Load a_2(D)

;; 2. Add a_2(D) + a_2(D) store result to temporary

;; 3. Store results to _1

(insn 7 4 8 2 (set (reg:SI 45)

(mem/c:SI (reg/f:SI 36 virtual-stack-vars) [1 a+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 -1

(nil))

(insn 8 7 9 2 (set (reg:SI 46)

(plus:SI (reg:SI 45)

(reg:SI 45))) "../func.c":2 -1

(nil))

(insn 9 8 10 2 (set (reg:SI 42 [ _1 ])

(reg:SI 46)) "../func.c":2 -1

(nil))a

;; _4 = _1 + b_3(D);

;; This is expanded to:

;; 1. Load b_3(D)

;; 2. Do the Add and store to _4

(insn 10 9 11 2 (set (reg:SI 47)

(mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 36 virtual-stack-vars)

(const_int 4 [0x4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 -1

(nil))

(insn 11 10 14 2 (set (reg:SI 43 [ _4 ])

(plus:SI (reg:SI 42 [ _1 ])

(reg:SI 47))) "../func.c":2 -1

(nil))

;; return _4;

;; We put _4 into r11 the openrisc return value register

(insn 14 11 18 2 (set (reg:SI 44 [ <retval> ])

(reg:SI 43 [ _4 ])) "../func.c":2 -1

(nil))

(insn 18 14 19 2 (set (reg/i:SI 11 r11)

(reg:SI 44 [ <retval> ])) "../func.c":3 -1

(nil))

(insn 19 18 0 2 (use (reg/i:SI 11 r11)) "../func.c":3 -1

(nil))The Virtual Register Pass

The virtual register pass is part of gcc/function.c file which has a few different

passes in it.

$ grep -n 'pass_data ' gcc/function*

gcc/function.c:1995:const pass_data pass_data_instantiate_virtual_regs =

gcc/function.c:6486:const pass_data pass_data_leaf_regs =

gcc/function.c:6553:const pass_data pass_data_thread_prologue_and_epilogue =

gcc/function.c:6747:const pass_data pass_data_match_asm_constraints =

Virtual Register Output

Here we can see that the previously seen variables stored to the frame at

virtual-stack-vars memory locations are now being stored to memory offsets of

an architecture specifc register. After the Virtual Registers pass all of the

virtual-* registers will be eliminated.

For OpenRISC we see ?fp, a fake register which we defined with macro

FRAME_POINTER_REGNUM. We use this as a placeholder as OpenRISC’s frame

pointer does not point to stack variables (it points to the function incoming

arguments). The placeholder is needed by GCC but it will be eliminated later.

On some arechitecture this will be a real register at this point.

;; Here we see virtual-stack-vars replaced with ?fp.

(insn 2 5 3 2 (set (mem/c:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp) [1 a+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 3 r3 [ a ])) "../func.c":1 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 3 2 4 2 (set (mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp)

(const_int 4 [0x4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 4 r4 [ b ])) "../func.c":1 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 7 4 8 2 (set (reg:SI 45)

(mem/c:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp) [1 a+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 8 7 9 2 (set (reg:SI 46)

(plus:SI (reg:SI 45)

(reg:SI 45))) "../func.c":2 2 {addsi3}

(nil))

(insn 9 8 10 2 (set (reg:SI 42 [ _1 ])

(reg:SI 46)) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 10 9 11 2 (set (reg:SI 47)

(mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp)

(const_int 4 [0x4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

;; ...The Split and Combine Passes

The Split passes use define_split definitions to look for RTL expressions

which cannot be handled by a single instruction on the target architecture.

These instructions are split into multiple RTL instructions. Splits patterns

are defined in our machine description file.

The Combine pass does the opposite. It looks for instructions that can be combined into a signle instruction. Having tightly defined predicates will ensure incorrect combines don’t happen.

The combine pass code is about 15,000 lines of code.

14950 gcc/combine.c

The IRA Pass

The IRA and LRA passes are some of the most complicated passes, they are responsible to turning the psuedo register allocations which have been used up to this point and assigning real registers.

The Register Allocation problem they solve is NP-complete.

The IRA pass code is around 22,000 lines of code.

3514 gcc/ira-build.c

5661 gcc/ira.c

4956 gcc/ira-color.c

824 gcc/ira-conflicts.c

2399 gcc/ira-costs.c

1323 gcc/ira-emit.c

224 gcc/ira.h

1511 gcc/ira-int.h

1595 gcc/ira-lives.c

22007 total

IRA Pass Output

We do not see many changes during the IRA pass in this example but it has prepared us for the next step, LRA/reload.

(insn 21 5 2 2 (set (reg:SI 41)

(unspec_volatile:SI [

(const_int 0 [0])

] UNSPECV_SET_GOT)) 46 {set_got_tmp}

(expr_list:REG_UNUSED (reg:SI 41)

(nil)))

(insn 2 21 3 2 (set (mem/c:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp) [1 a+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 3 r3 [ a ])) "../func.c":1 16 {*movsi_internal}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 3 r3 [ a ])

(nil)))

(insn 3 2 4 2 (set (mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp)

(const_int 4 [0x4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 4 r4 [ b ])) "../func.c":1 16 {*movsi_internal}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 4 r4 [ b ])

(nil)))

(insn 7 4 8 2 (set (reg:SI 45)

(mem/c:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp) [1 a+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 8 7 9 2 (set (reg:SI 46)

(plus:SI (reg:SI 45)

(reg:SI 45))) "../func.c":2 2 {addsi3}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 45)

(nil)))

(insn 9 8 10 2 (set (reg:SI 42 [ _1 ])

(reg:SI 46)) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 46)

(nil)))

(insn 10 9 11 2 (set (reg:SI 47)

(mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp)

(const_int 4 [0x4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

;; ...The LRA Pass (Reload)

The Local Register Allocator pass replaced the reload pass which is still used by some targets. OpenRISC and other modern ports use only LRA. The purpose of LRA/reload is to make sure each RTL instruction has real registers and a real instruction to use for output. If the criteria for an instruction is not met LRA/reload has some tricks to change and instruction and “reload” it in order to get it to match the criteria.

The LRA pass is about 17,000 lines of code.

1816 gcc/lra-assigns.c

2608 gcc/lra.c

362 gcc/lra-coalesce.c

7072 gcc/lra-constraints.c

1465 gcc/lra-eliminations.c

44 gcc/lra.h

534 gcc/lra-int.h

1450 gcc/lra-lives.c

1347 gcc/lra-remat.c

822 gcc/lra-spills.c

17520 total

During LRA/reload constraints are used to match the real target inscrutions, i.e.

"r" or "m" or target speciic ones like "O".

Before and after LRA/reload predicates are used to match RTL expressions, i.e

general_operand or target specific ones like reg_or_s16_operand.

If we look at a test.c.278r.reload dump file we will a few sections.

- Local

- Pseudo live ranges

- Inheritance

- Assignment

- Repeat

********** Local #1: **********

...

0 Non-pseudo reload: reject+=2

0 Non input pseudo reload: reject++

Cycle danger: overall += LRA_MAX_REJECT

alt=0,overall=609,losers=1,rld_nregs=1

0 Non-pseudo reload: reject+=2

0 Non input pseudo reload: reject++

alt=1: Bad operand -- refuse

0 Non-pseudo reload: reject+=2

0 Non input pseudo reload: reject++

alt=2: Bad operand -- refuse

0 Non-pseudo reload: reject+=2

0 Non input pseudo reload: reject++

alt=3: Bad operand -- refuse

alt=4,overall=0,losers=0,rld_nregs=0

Choosing alt 4 in insn 2: (0) m (1) rO {*movsi_internal}

...

The above snippet of the Local phase of the LRA/reload pass shows the contraints

matching loop for RTL insn 2.

To understand what is going on we should look at what is insn 2, from our

input. This is a set instruction having a destination of memory and a source

of register type, or "m,r".

(insn 2 21 3 2 (set (mem/c:SI (reg/f:SI 33 ?fp) [1 a+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 3 r3 [ a ])) "../func.c":1 16 {*movsi_internal}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 3 r3 [ a ])

(nil)))RTL from .md file of our *movsi_internal instruction. The alternatives are the

constraints, i.e. "=r,r,r,r, m,r".

(define_insn "*mov<I:mode>_internal"

[(set (match_operand:I 0 "nonimmediate_operand" "=r,r,r,r, m,r")

(match_operand:I 1 "input_operand" " r,M,K,I,rO,m"))]

"register_operand (operands[0], <I:MODE>mode)

|| reg_or_0_operand (operands[1], <I:MODE>mode)"

"@

l.or\t%0, %1, %1

l.movhi\t%0, hi(%1)

l.ori\t%0, r0, %1

l.xori\t%0, r0, %1

l.s<I:ldst>\t%0, %r1

l.l<I:ldst>z\t%0, %1"

[(set_attr "type" "alu,alu,alu,alu,st,ld")])The constraints matching interates over the alternatives. As we remember from above we are trying to match "m,r". We can see:

alt=0- this shows 1 loser because alt 0r,rvsm,rhas one match and one mismatch.alt=1- is indented and saysBad operandmeaning there is no match at all withr,Mvsm,ralt=2- is indented and saysBad operandmeaning there is no match at all withr,Kvsm,ralt=3- is indented and saysBad operandmeaning there is no match at all withr,Ivsm,ralt=4- is as win as we matchm,rOvsm,r

After this we know exactly which target instructions for each RTL expression is neded.

End of Reload (LRA)

Finally we can see here at the end of LRA/reload all registers are real. The output at this point is pretty much ready for assembly output.

(insn 21 5 2 2 (set (reg:SI 16 r17 [41])

(unspec_volatile:SI [

(const_int 0 [0])

] UNSPECV_SET_GOT)) 46 {set_got_tmp}

(nil))

(insn 2 21 3 2 (set (mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 2 r2)

(const_int -16 [0xfffffffffffffff0])) [1 a+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 3 r3 [ a ])) "../func.c":1 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 3 2 4 2 (set (mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 2 r2)

(const_int -12 [0xfffffffffffffff4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])

(reg:SI 4 r4 [ b ])) "../func.c":1 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(note 4 3 7 2 NOTE_INSN_FUNCTION_BEG)

(insn 7 4 8 2 (set (reg:SI 16 r17 [45])

(mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 2 r2)

(const_int -16 [0xfffffffffffffff0])) [1 a+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 8 7 9 2 (set (reg:SI 16 r17 [46])

(plus:SI (reg:SI 16 r17 [45])

(reg:SI 16 r17 [45]))) "../func.c":2 2 {addsi3}

(nil))

(insn 9 8 10 2 (set (reg:SI 17 r19 [orig:42 _1 ] [42])

(reg:SI 16 r17 [46])) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

(insn 10 9 11 2 (set (reg:SI 16 r17 [47])

(mem/c:SI (plus:SI (reg/f:SI 2 r2)

(const_int -12 [0xfffffffffffffff4])) [1 b+0 S4 A32])) "../func.c":2 16 {*movsi_internal}

(nil))

;; ...Conclusion

We have walked some of the passes of GCC to better understand how it works.

During porting most of the problems will show up around expand, vregs and

reload passes. Its good to have a general idea of what these do and how

to read the dump files when troubleshooting. I hope the above helps.

Further Reading

- All of GCC’s passes - a complete view of the passes

- GCC Internals Passes [pdf] - a presentation from Diego Novillo on passes, including how to write your own

- Variable Range Propagation - an article from Dr. Dobbs on VRP an interesting pass

- Compilers - a classic book on fundamentals of compiler design